Huge vapours brood above the clifted shore,

Night o’er the ocean settles, dark and mute,

Save where is heard the repercussive roar

Of drowsy billows, on the rugged foot

Of rocks remote; or still more distant tone

Of seamen, in the anchored bark, that tell

The watch reliev’d; or one deep voice alone

Singing the hour, and bidding “strike the bell.”

All is black shadow, but the lucid line

Mark’d by the light surf on the level sand,

Or where afar, the ship-lights faintly shine

Like wandering fairy fires, that oft on land

Mislead the pilgrim; such the dubious ray

That wavering reason lends, in life’s long darkling way.

– Charlotte Smith

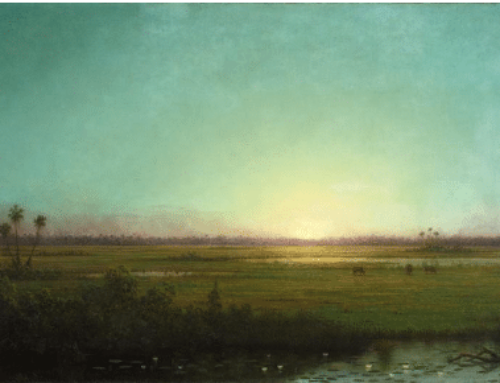

Charlotte Smith’s sonnet “Huge Vapours Brood above the Clifted Shore” captures the mysterious mood of seascapes at night, of moonlit churn, barely visible lights on a distant headland. It’s the visceral, dramatic mood of works like Ivan Aivasovsky’s painting above, where the moon illuminates a deserted beach to reveal a small boat washed ashore with two steamships in the background. A similar feeling broods behind Winslow Homer’s Wood Island Light (below).

Winslow Homer, Wood Island Light, oil, 30 3/4 x 40 1/4 in. (1894)

In this painting also, one of the many Homer painted near his home in Prout’s Neck, Maine, the moonlight adds an intense amount of drama. The moon itself is veiled by clouds and outside the frame, but its light alternately bleaches and gilds the surf, lights the waves its shining through and contrasts with the black rocks of the shoreline.

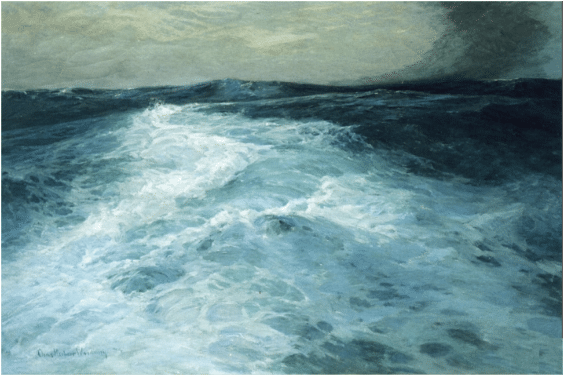

Charles Woodbury, Mid-Ocean, 0il, 1894

Charles Woodbury’s Mid-Ocean (above) takes a different approach but achieves a similar feeling. Here we’re at sea completely, no land visible. Dark swells eclipse the horizon, foreshadowing the arrival of the storm we see in the top right corner.

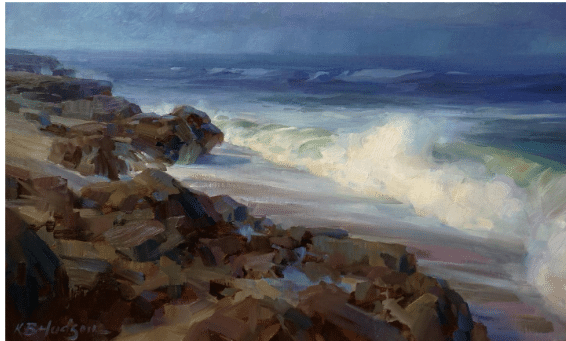

Kathleen Hudson, Rolling Surf, Oil on linen panel, 13 x 21 in.

Kathleen Hudson’s Rolling Surf is too bright to be a moonlit nocturne. However, her sky is on the dark side, and this adds quite a bit of atmosphere and drama. By tilting the rocks and sand on a diagonal, Hudson conveys the sense of movement as water at the tideline washes back into the sea as the next wave crests and crashes.

Esoterica: Charlotte Smith’s sonnet seems to tease something out of the drama in those dark and stormy ocean paintings: on some level perhaps, the “treacherous sea” archetype reminds us of the difficulties we all sometimes face during our “voyage” through this life.

Beneath the “huge vapours” of the poem’s looming storm, where “all is black shadow,” the speaker says there are but two points of light to guide the wanderer: one, the “lucid” but unstable line where the sea meets the shore, the other the distant ships’ lights that beckon us into dangerous oceans – such, the last line suggests, is the “dubious” light of “wavering reason” as we progress along “life’s long darkling way.”

Surely the writer’s life was no pleasure cruise. In 1700s England, Smith narrowly managed to free herself and her nine children from a horrific marriage to a ne’er do well prosecuted for debt. After that, she went it alone and wrote over 60 books of poetry and prose including essays, articles, and children’s stories, to support herself and large family. She struggled with poverty and died fighting through the legal system for money she was owed.

Kathleen Hudson shares her oil painting technique in the video Creating Dramatic Atmosphere in Landscapes. You can browse multiple approaches to painting the ocean here.

Artist to Watch: Devin Cecil-Wishing

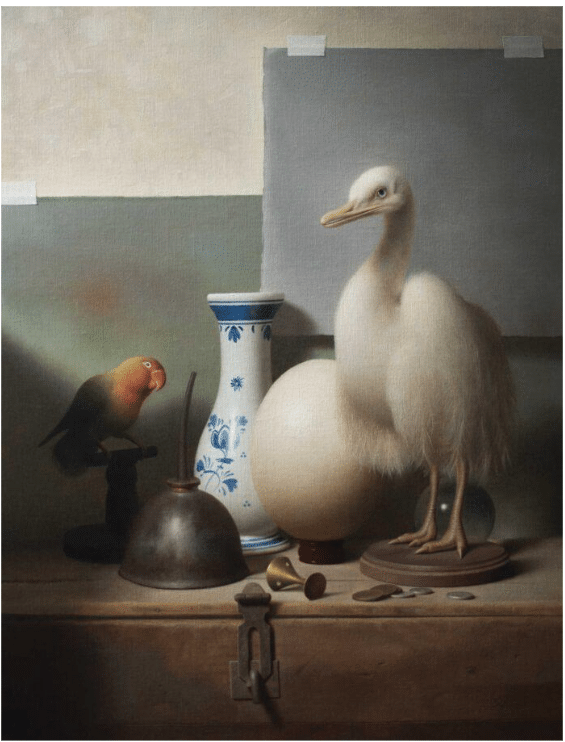

Devin Cecil-Wishing, “Rhea,” 2023, oil on linen, 24 x 18 in., private collection

There is a lot of superb contemporary realism being made these days; this article by Allison Malafronte shines light on a gifted individual.

Devin Cecil-Wishing (b. 1981) is one of hundreds of millennial-aged artists who, despite living in a tech-centric, modern culture, found their way to a classical atelier that still teaches Old Master methods and materials. That school is the well-known Grand Central Atelier in New York City, but that was not Cecil-Wishing’s starting point for his art training and career.

That goes back more than a decade prior when, after discovering the work of underground cartoonist R. Crumb (b. 1943), he attended the San Francisco School of the Arts High School. Cecil-Wishing went on to study illustration at what is now called California College of the Arts, where he developed an interest in 1960s poster art, surrealism, and wildlife art. After graduation, a trip to the Netherlands brought Cecil-Wishing face-to-face with Rembrandt’s “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp“ at the Mauritshuis, and he had an epiphany: he loved traditional painting. Returning to San Francisco, he studied at the Atelier School of Classical Realism in Oakland and then in 2009 made his way to Grand Central, where he currently teaches and paints.

Still one for curiosity-satisfying travel to fill his creative cup, Cecil-Wishing painted “Rhea” (illustrated above) after another museum-inspired aha moment.

“The main inspiration for this piece was an experience I had this past summer while visiting the Kunsthistoriches Museum in Vienna,” the artist explains. “I found myself surrounded by Peter Paul Rubens and Frans Snyders paintings when I was suddenly struck by a realization that painting is an entire language, existing completely apart from the visual world in front of us. Just as the word ‘horse’ bears little resemblance to an actual horse, a painting of a horse needn’t necessarily be a recreation of the optical appearance of seeing a horse at all. Rather, it may just need to form the visual idea of a horse in a convincing enough way to make the viewer believe it is real.”

Cecil-Wishing continues, “It suddenly occurred to me that a depiction of an object could be absolutely, convincingly believable, while simultaneously bearing little to no resemblance at all to the optical experience of looking at the real thing. There was a language being spoken in the canvases in front of me — one which we can all somehow read, despite the fact that so few can actually speak it. Much of what inspires me to paint is the idea of learning to speak in the language of painting, as fluently and deeply as possible. ‘Rhea’ is an exercise in that realization.”

This article was originally published in Fine Art Connoisseur magazine (subscribe here).