“It has always seemed to me that a picture does not rest upon beauty alone.”

– John Carlson

Paintings, like people, have an outer surface that they present to the world and an “inner life” that may or may not fully reveal itself to those who get to know them. In my opinion, we best get to know and like (or not like) a person – or a painting – based on personality, not just “looks.” For that, we must make the effort to interact.

Plenty of strong paintings rely on the most pleasing visible qualities a subject possesses, be it flower, barn, boat, or meadow. However, going beyond technique and even subject matter, every great painting has its own “inner life,” just as each artist does. And it has this deeper resonance because the artist put it there – not by consciously thinking about it, just by feeling it. Perhaps “feeling into the painting” would be a good way to put it.

Not every painting has to convey a deep feeling, but it’s very nice when one does. You have to want to create something meaningful with your work before you will be able to do so. It’s not that you have to know “what your painting means” before you paint it. (Who knows what any painting really means anyway?) It’s more a question of not leaning so heavily on technique-for-its-own sake and putting your knowledge and tools at the service of a feeling about your subject, something you feel is important enough to share with others.

In practical terms, this could mean not just “painting a flower” but painting a rakish dahlia glowing with the electric current of life; not just a barn but a human structure clearly standing in defiance of nature’s superior forces; not a field but an unruly meadow humming with late summer insects and light; not just a boat but a dory so weathered and soaked in salt, wind, sunlight, and shadow that it looks old enough to belong to “death the ferryman” himself.

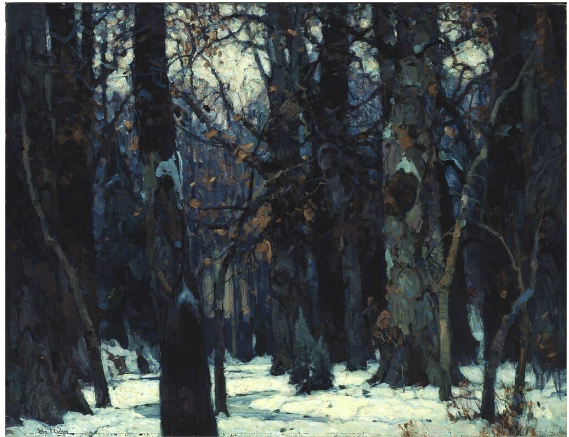

John F. Carlson, Brooding Silence, oil on canvas, 37 1⁄8 x 52 in.

For an example, let’s take a painting by John Carlson titled Brooding Silence (above). Let’s get this right out of the way: it looks nothing like a photograph. It isn’t just an image of trees in the snow – it’s not just an artful arrangement of color and descriptive details.

Rather, it’s the visual trace of an experience – the deep indigo darks, the muted, jewel-like lights – the spectacle of the overall entanglement of dark and light – it all renders what we find in the title: not just woods but Brooding Silence.

This painting is “about” a moment of profound experience; it was painted with that in mind, and that is why it’s so good. That’s also why it was owned by Henry Ward Ranger himself (a great American landscapist) and why it now resides in the Smithsonian American Museum of Art.

Of course there’s solid technique, mastery of the medium, etc., but Carlson also very clearly and decisively brought his desire to share an experience to bear on his choices about color, value, shapes and depth. On some level, Carlson knew that the true unspoken subject of a memorable painting comes down to not just what it is a paintings of, but what it can make us see and feel. As Carlson sums it all up, “The beauty and the recognized elements of subject matter (with the unity of idea in which they should be represented) together signify something to us.” That’s the “inner life” of a painting.

So, how on earth do you do that? How do you get yourself into your paintings? Some people say it just happens while you’re concentrating on other things. I think it helps if you consciously push yourself to do it.

To balance technique with expression it’s necessary to risk showing one’s feelings, owning your take on the world. One must consciously prioritize the desire to express one’s deepest experience of the thing, placing it very near the top of the list of the many other reasons we make paintings.

You already know how you feel about the world and the things inside it – and you probably already know enough about painting to start getting some of that into your work. Try it. Let down your guard and risk a painting or two from the hip.

Who cares what others think? You don’t have to show anybody, just do it for yourself, and judge these experiments for their promise and potential for future paintings, not as finished work in themselves (that comes later). Just know that color, line, and visual weight are not only the tools of painting; they’re also the tools of expression.

Why not consider pushing your current work’s boundaries and see what you can discover of yourself there.

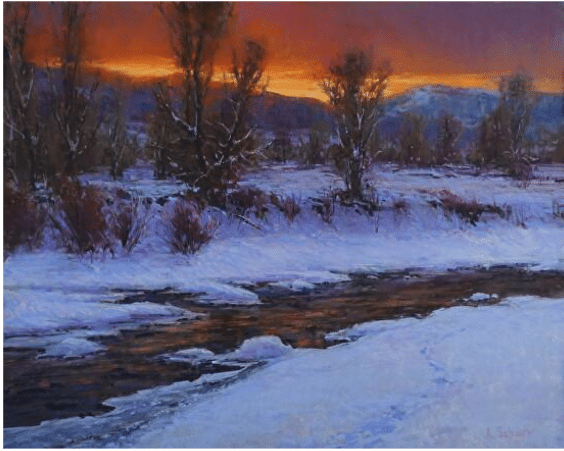

Joshua LaRock, Drawing on the Water, oil, 24″ x 24” Joshua LaRock is an accomplished portrait and figure painter who shares his approach in his video Classical Portraits. Check it out here.

Breath-catching paintings combine the character of a thing (as the artist perceives it) with the painter’s technical knowledge and developed instinct of how best to represent his or her own experience so that others see it too. You don’t have to know everything about how to paint before you can do this; all you have to do is change your attitude about painting. I think you can uncover a personal vision while developing the skill to express it at the same time; it’s through making the work that we find ourselves.

What will your work look like when you resolve uncompromisingly to start with feeling, to put feeling first, and carry it forward from there?

Between Worlds: Steven DaLuz Takes Off

Steven DaLuz, Between Worlds, oil and mixed media, 36” x 48”

Steven DaLuz won a November 2023 PleinAir Salon honorable mention for work by an artist over the age of 65.

DaLuz is a highly successful realist, known for larger-scale figurative works and imagined landscapes created by a process he devised involving metal leaf, oil, and mixed mediums, as well as encaustic.

Born in Hanford, California, Steve retired from the Air Force after living 13 years abroad. He completed a BA degree in Social Psychology, and an MA in Management, before earning a BFA in 2003. His drawings and paintings are represented in private and corporate collections in 34 states and overseas.

Look for a feature on Steven and his work in an upcoming edition of Inside Art.