“I never in my life saw more horrible things… They do not observe drawing nor form, but give you an impression of what they call nature. It was worse than the Chamber of Horrors.”

– J. Alden Weir, on viewing Impressionism in Paris in 1877

J. Alden Weir traded a painting of a flower for a farm in Connecticut that totally transformed his painting.

Art historians consider Weir (1852-1919) an American Impressionist, although he initially hated the style, an exhibition of which in 1877 he called “worse than the Chamber of Horrors.”

He couldn’t have known, at age 25, that Impressionism would eventually completely eclipse realism, transform his own style in the process, and take the work by storm with its fresh, indeed revolutionary, influence that is still being practiced and taught by leading painters today.

“My name is J. Alden Weir and I do not approve this abomination .. whatchmacalit “Impressionism” thing.

To be fair to Weir, the style was as radical as it was new. Just three years earlier had seen Impressionism’s coming out party: A loosely knit band of young rebel painters mounted their own unsanctioned exhibition in an empty carriage garage on the same Parisian street as the famed Salon. A reviewer, one of many dismissive and disdainful critics of that 1874 show, dubbed the band of anti-artists “Impressionists” after the title of Monet’s entry, Impression, Sunset. So began a revolution in Western art.

In June of 1882, art collector Erwin Davis offered Weir a 155-acre farm in the Branchville neighborhood of Ridgefield, Connecticut in exchange for a “flower” painting from Weir’s private collection. Intrigued by the offer, Weir made the trip from New York City to see the farm. He quickly agreed to the sale. On July 19, 1882, the Davises signed the deed which formally transferred the property to Weir.

The title of the flower painting and its artist (probably not Weir) are the stuff of cold case art history episodes on Netflix (if there were such a thing – you need to go to the BBC for that).

J. Alden Weir, Spring Landscape, Branchville, 1882 Watercolor on Paper

Weir fell in love with the place. There he painted both beautiful vistas and dying trees, believing that common subjects are beautiful and worth examining. Truly a plein-air painter’s paradise it was and is, with more than 60 acres of painterly woods, fields, and waterways. Weir described it as the “Great Good Place,” and you can go and p-and paint there too! Today, Weir Farm is open to the public, a plein-air mecca of a national park, with its own teaching “Impressionist artist-in-residence.”

J. Alden Weir, Lengthening Shadows, 1887. Unusual composition! Note the dead log barring our way.

Weir came to Impressionism in a big way, all at once, but not until about 1890, 13 years after he initially dismissed Impressionist paintings done, to his naive eye, “without drawing nor form,” as “horrible things.”

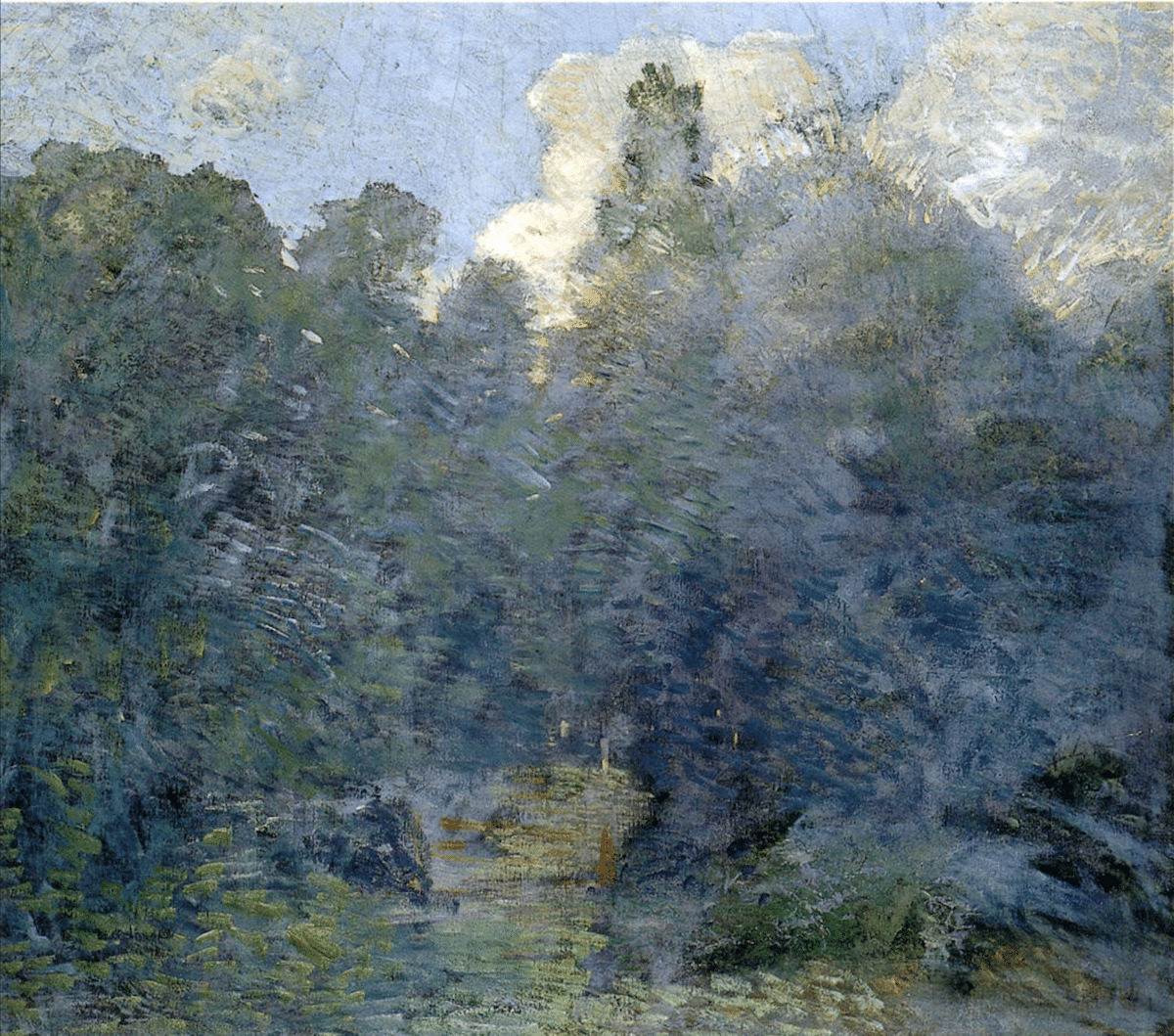

J. Alden Weir, Autumn Rain, 1890. Ah, now we’re really getting into the Impressionism/Tonalism thing.

It was then and there that Weir had his revelation – he suddenly “got” Impressionism. For the first time in his life, Weir found himself painting the pastures, groves, streams, and fields with an Impressionistic fervor soaked with feeling for nature’s beauty, finally giving himself up to “an impression of what they call nature.” He debuted his new Impressionistic painting style in an 1891 exhibit at the Blakeslee Gallery in New York City.

Unfortunately, critics wrote mostly negative reviews, exclaiming the paintings were “less refined in quality than Mr. Weir knows how to make.” Even his brother, artist John Ferguson Weir, didn’t understand the exhibit and all and called him a fool.

J. Alden Weir, Autumn, Oil on Canvas 1906 Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, William A. Clark Collection.

In response Weir wrote his brother, “I have exhibited these things because I recognize in them a truth which I have never felt before…my eyes, I feel, have been opened to a big truth.” His big truth was to create paintings that showed what he called the “character and aspect” of the subject; not necessarily a realistic representation of what he saw.

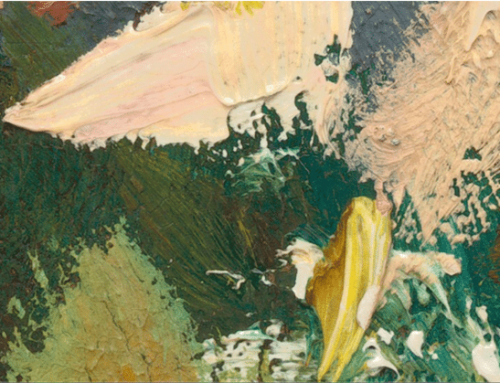

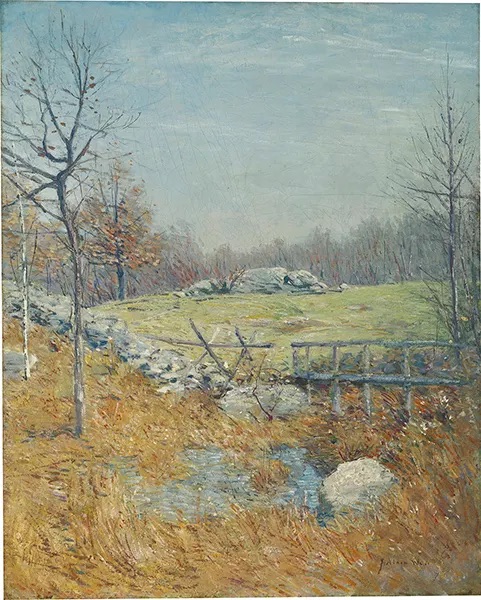

J. Alden Weir, The Open Barway, Oil on Canvas, ca. 1910

“I don’t like what others find attractive,” Weir once wrote. When he said this, he was speaking about a winding country road, but the same could apply to his bridge painting or to The Open Barway (directly above). A barway is an opening in a stone wall for wagons to drive through. This is the not the beautiful landscape that one would expect at first glance. Note the dead tree dominating the foreground and the vista of the landscape broken up by the intersection of several stone walls. Even the two stately trees in the background are cut off.

As the viewer’s eye moves past the dead branches drooping across the foreground, we take in the sun lighting up a small, pink tree hidden behind the bare branches . Only the ends of the stone wall and courtyard are bathed in sunlight, with most of the painting (as in Lengthening Shadows at the top of this page) given over to shade.

Staying True to His Roots

While staying at the farm, Weir cultivated his friendship with John Henry Twachtman, who lived 28 miles away in Greenwich, CT. Much like Weir, Twachtman was primarily an American landscape artist whose style combined the techniques of Impressionism and Tonalism.

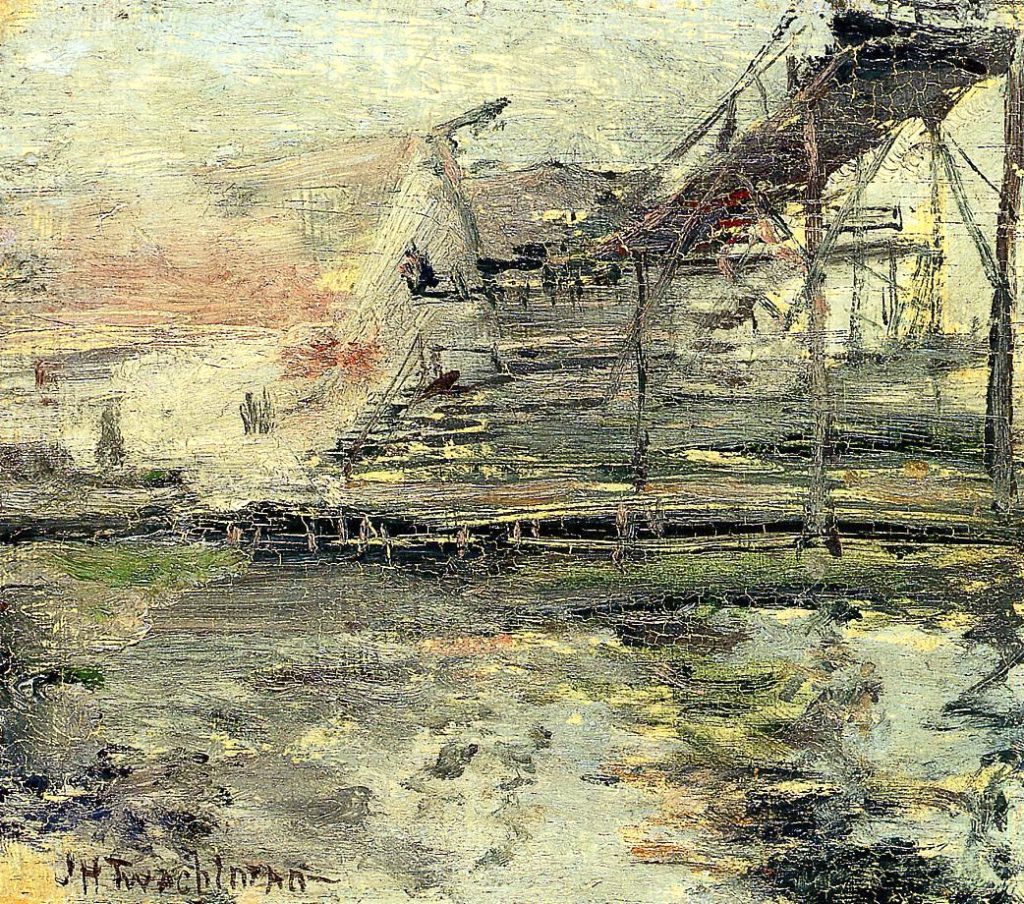

John Henry Twachtman, Harbor Scene, 1902

Twachtman’s work, much like Weir’s, was filled with farm pastures, old houses, waterways and meadows, punctuated by the occasional gritty harbor or rustic bridge, rendered at times in lush greens at others in muted earth tones. The two artists shared a keen ability to convey emotion and unconventional beauty in their work. They often painted and exhibited together, and both taught at the Art Student’s League in New York.

J. Alden Weir, The Red Bridge, 1895

Art historians consider Weir’s The Red Bridge one of his best works. Its staccato, directional brushwork shows just how much of Impressionism Weir ended up embracing. The subject, however, a railroad trestle seen at a rakish angle, and the unusual, cropped composition, speak to what was fresh in Weir’s work and underscores his adaptation (as opposed to imitation) of the Impressionist approach for rendering genuinely observed American imagery in his moment in place and time.

Weir Farm is currently showing an exhibition of Weir’s Impressionistic works produced at the “Great Good Place” after he changed his style.

Portrait of Weir in 1890 by John Singer Sargent