“Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire.”

― Gustav Mahler

Art has a long history (to say the least) of practice, tradition, and training. And yet, art remains forever fresh and new for each new practitioner. That’s part of its endless appeal in the popular imagination – when someone says, “You’re an artist?” with something like admiration, maybe a touch of awe, they’re imagining what it would be like to trust oneself implicitly, to live fully and authentically, with imagination, beauty, and truth as constant companions (Ha! If they only knew…!).

As an artist, it’s a given that you have to learn the basics of composition, drawing, edges, color, the principles and techniques passed from master to student for hundreds of years. Yet, there’s so much to internalize and develop that often expression, the very thing that drives creativity in the first place, gets left behind. For the creative artist, technique and tradition are tools, not ends in themselves, and both are needed.

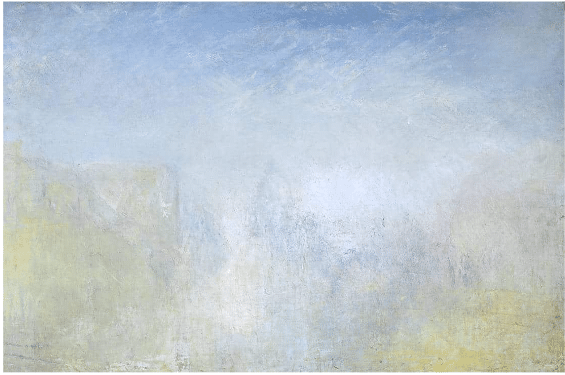

Take JMW Turner for example. Turner was an artist so thoroughly a master of the techniques of painting that he was enrolled in the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts while still a boy of 14. Had he kept on producing such paintings, he would probably have been elected to head of the Academy eventually and very few people today would know his name. When Turner put what he’d learned of technique and tradition entirely at the service of a personal understanding of life and beauty, he developed his own “painting language” to do it in. The Academy called him mad. And here we are talking about Turner instead of … who?

J.M.W. Turner, Venice with the Salute, c.1840-5 Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

After all, every standard academic technique was once somebody’s “what if…? A painter’s vision once demanded an expression with enough force that a technique was born and then universally adopted.

Still, somehow we’re supposed to find our authentic voice AND learn the secrets of conjuring three-dimensional forms onto a two-dimensional surface – the stages of building a painting through design and draftsmanship which tools to use and how, etc. etc. It’s a lot!

Therefore, many stick to the well-travelled path, believing that departing yields nothing but disaster; our horror at our failed paintings send us back to what we know will “work.” We conclude that we’re not that kind of artist, or maybe someday we’ll have the confidence and ability to strike out on our own, but definitely not now – our disastrous attempts prove it. But this is a huge mistake.

The real problem here is not the inability to create something of value – it’s our inability to see what’s of value in what we create.

Seeing Our Own Worth

In other words, we spend so much time and energy developing the proper techniques of making good paintings, that when we step outside those parameters, of course what we create looks like a failure – it doesn’t check any of the boxes we’ve learned are “supposed to be” checked.

Raphael was very much a painter of his time – the Italian Renaissance

And yet, and you already know this on some level, in each “hot mess” you make, there’s a little of yourself in there. There’s something unlearned, uncontrived, honest, and raw, something that corresponds to how you really feel and who you really are in the world. See that. Honor it.

You don’t have to show those paintings to anyone, but make them, keep them (even if you can barely bring yourself to look at them). Own them for what they are and what they could have been. Often there’s an idea of value there, it’s just that the technique hasn’t caught up yet. In this way, the so-called failures are the flagstones that lead to authenticity.

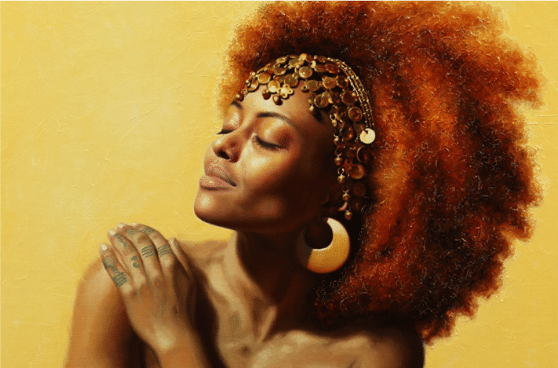

Vicki Sullivan, Rapture, Oil on Linen, 40cm x 50cm x .3 Vicky teaches her approach to the portrait in the video, Painting Realistic Portraits.

Eventually, when you can allow your emotion to lead but not dominate, you will begin to combine technique and personal expression in the free interpretation of what you see and know.

Here are three ideas for stretching yourself as you seek beyond your boundaries:

- Find out what artists do. Seek out an historical artist whose work you respond to immensely and learn everything you can about them as a person. The only requirement is that they be dead. Do some deep-dive art history searches. Find the originators of what everyone is copying: find yourself a Sargent, a Turner, a Klee, a Raphael, Constable or Latour. Don’t settle for free YouTube documentaries; splurge on real art books and read the words in them. Find out what the critics, then and now, as well as what the artist had to say about the work. Seriously, go see the work in person whenever you can. Don’t study them to learn how to use oil paint, watercolor, or pastels; the most important lesson the masters can teach you isn’t about technique – it’s about what inspired them to make the work they did.

- Look at different kinds of art. We tend to gravitate to a particular genre of art and the artists who make it, but there are many art worlds. Stumble onto a few of them now and again. Follow some unfamiliar links online, read about art you aren’t even initially interested in, discover new galleries and seriously consider the merit of the work they show. Always be open to expanding your definition of art.

- Figure out what you have to say. Knowing yourself is a huge advantage as an artist. Ask yourself what you like about the work you admire – not just in terms of technique, but in terms of what’s behind it, what the artist put into it, what the work conveys about life! What’s important to you? As Walt Whitman wrote, “the passionate play goes on – and you can contribute a verse.”

Design is probably the most important and most easily assimilated aspect of traditional technique. For a thorough overview, you might want to consider an instructional DVD such as William A. Schneider: Design Secrets of Masters – Key to a Successful Painting

Italian Artist’s ‘Alchemical’ Paintings Charm New York

Pier Paolo Calzolari makes paintings that New York City shouldn’t like, given the kind of conceptual and more socially inflected work that has been wowing critics of late. Yet Calzolari’s return to a New York gallery after an absence of five years was a critical triumph, and much of the work is magical – straightforward, honest, poetic, and rich with semi-abstract natural-spiritual mystery.

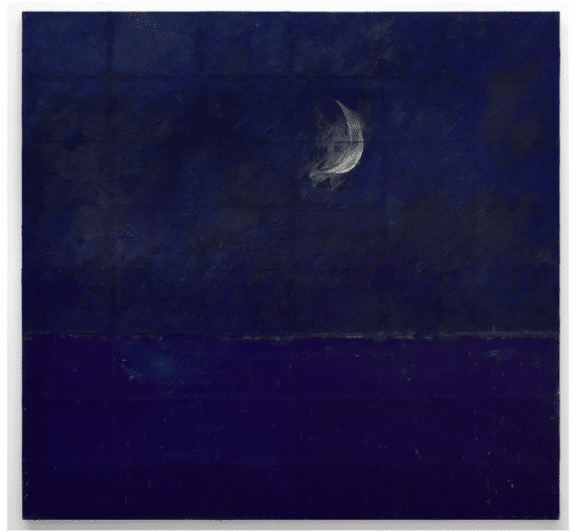

Senza titolo [Luna] / Untitled [Moon], 1979, Wax water tempera, egg tempera and oil on cardboard pieces glued on wood, 74″ x 78″

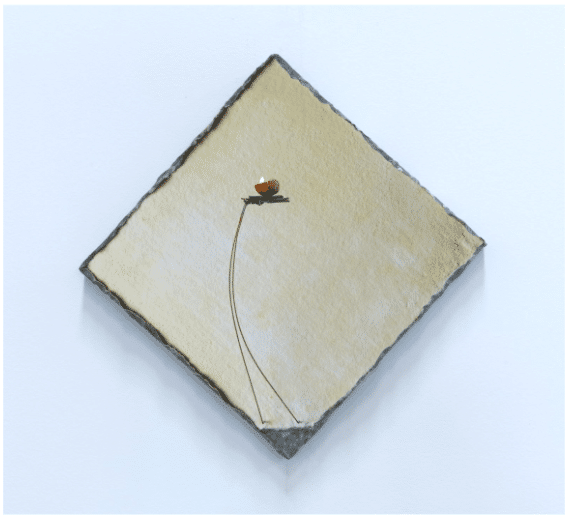

While the artist continues to incorporate sculptural elements made of organic matter such as salt, feathers, clover petals, and seashells, he is now using raw pigment powders and tempera in startlingly saturated colors. The luminous canvases include fields of intense primary yellows, reds, blues, and whites with varying surfaces and textures that call to mind nature in the form of sunlight, fire, and a night sky, making this exhibition a meditation on the transience and the delicate beauty of everyday life.

Pier Paolo Calzolari, Studio, 1980, Salt on cardboard, copper, lead, snail, oil candles, 25″

Pier Paolo Calzolari Untitled, 1976

Lead, copper, iron, oil lamps

37 1/3 x 49 1/2 x 3 1/4 inches 95 x 126 x 8 cm

Pier Paolo Calzolari, installation shot, Marianne Boesky Gallery, NYC. All photos courtesy of the gallery

The artist has said that “painting should be about getting lost finding oneself or finding oneself getting lost. But for me painting has always been, above all, a lover: I have a bond with it that comes from a fascination of the senses and, at the same time, the loss of the senses. Painting is the gesture that comes before the decision, the insecurity brought to economy.”