Like many of the Impressionists, Claude Monet loved to paint along the Normandy Coast. Monet produced more than 90 paintings of Étretat, one of the coast’s fishing village/resort towns. Now scattered among private and public collections around the world, these works show the famous natural site at different times of the day.

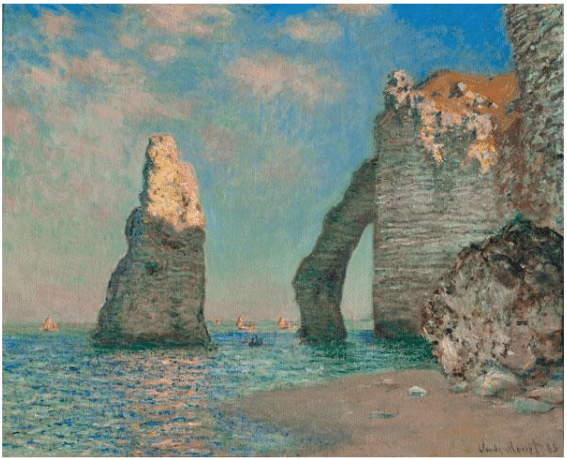

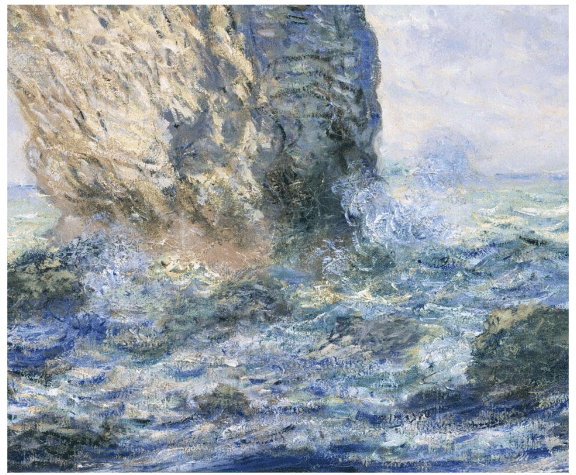

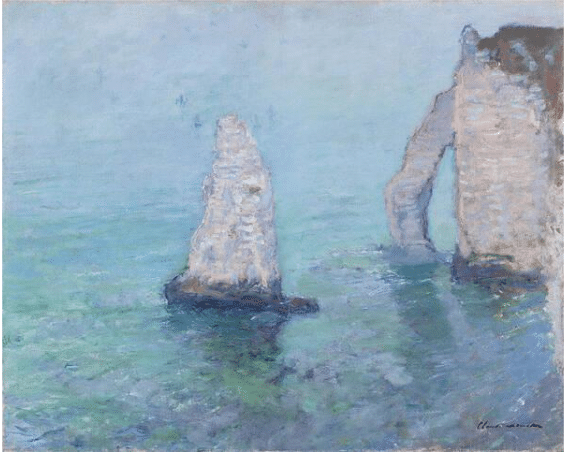

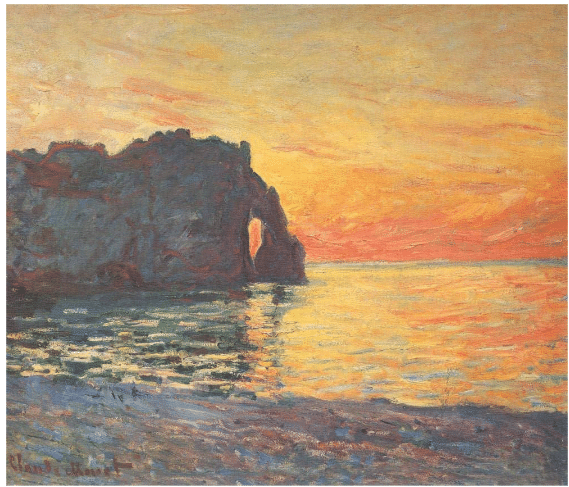

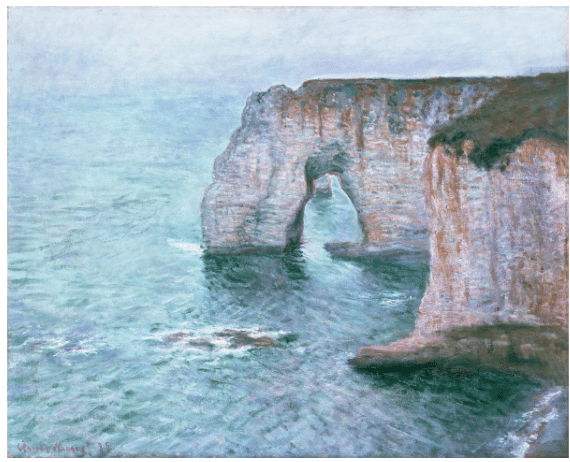

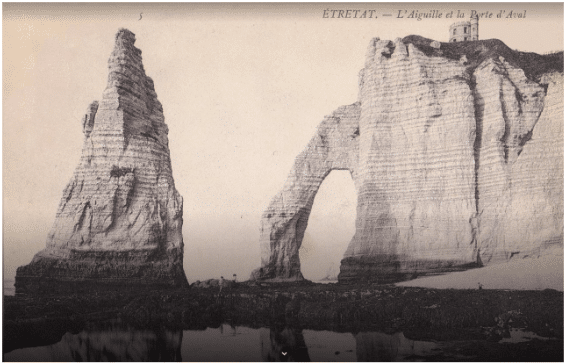

The 1885 painting above, titled The Cliffs at Étretat, shows the Porte d’Aval, a huge natural arch that jutted out into the sea. The natural rock formations and freestanding needle-like rocks attracted tourists and artists alike to Étretat.

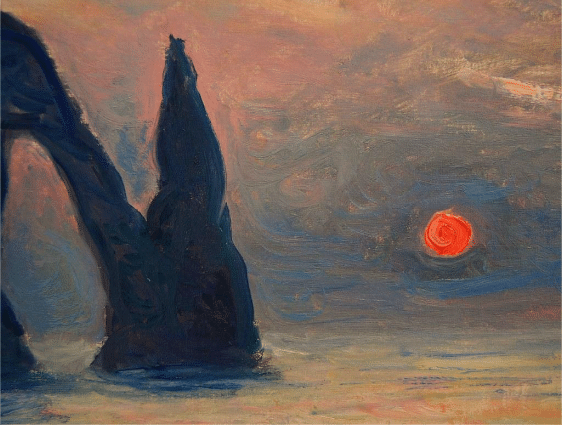

Detail, Claude Monet, The Cliffs at Étretat, 1886

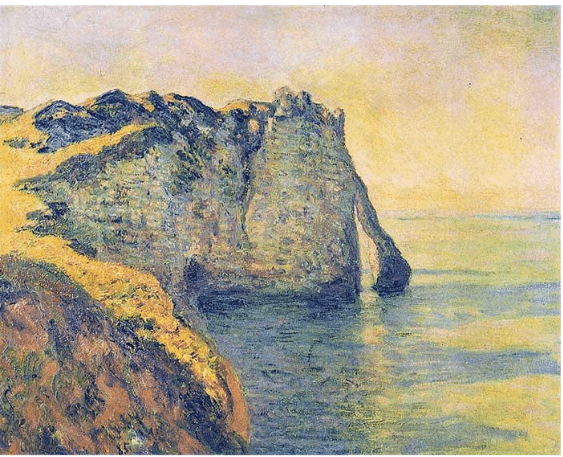

Between October and December 1885 alone, he made nearly fifty paintings at Étretat. In 1883, he’d painted 20 views of the beach and all three of the extraordinary rock formations in the area: the Porte d’Aval, the Porte d’Amont, and the Manneporte.

Monet painted several views of the cliffs from unusual locations, accessible only by boat or via a precipitous path. The writer Guy de Maupassant, who happened to be there at the same time as the famous artist, described how Monet “watched the sun and the shadows, capturing in a few brushstrokes a falling ray of light or a passing cloud.”

“The artist walked along the beach, followed by children carrying five or six canvases representing the same subject at different times of the day and with different effects,” he wrote. “He took them up and put them aside by turns according to changes in the sky and shadows.”

“I saw him catching a glittering fall of light on the white cliff and painting it with a flow of yellow tones that were strangely giving an amazing and fleeting impression of that elusive and blinding dazzle. In truth, he was no longer a painter, but a hunter.” (Guy de Maupassant, “La vie d’un paysagiste,” in “Gil Blas,” September 28, 1886, p. 1).

Claude Monet, Cliffs Of The Porte d’Aval, 1885

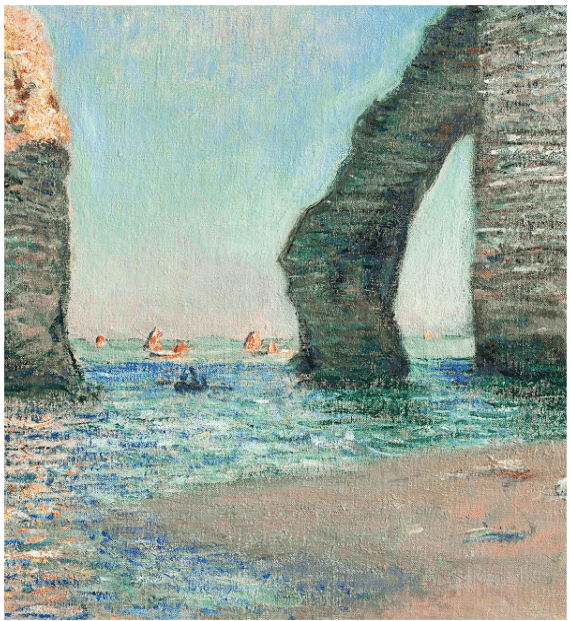

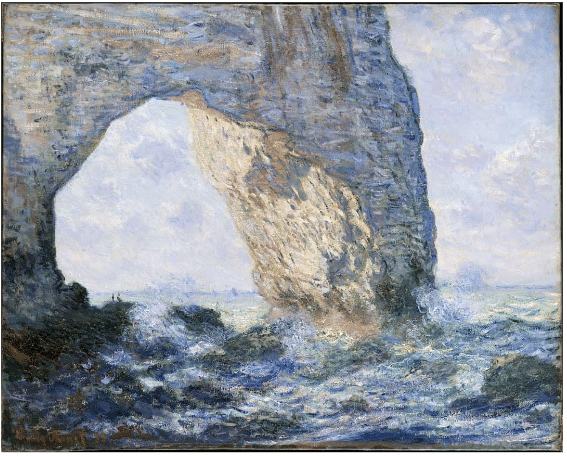

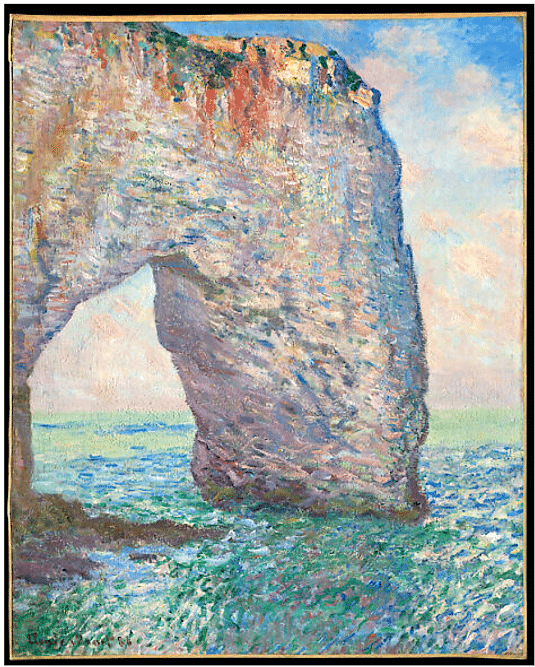

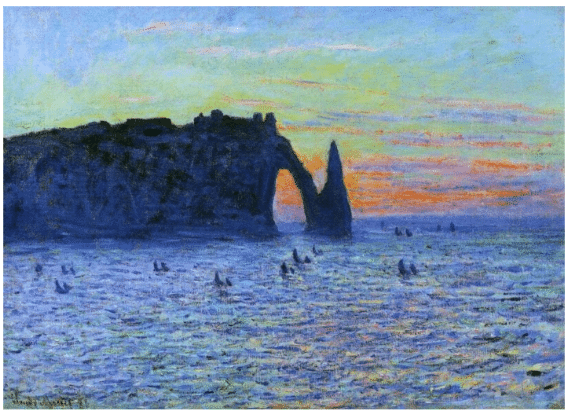

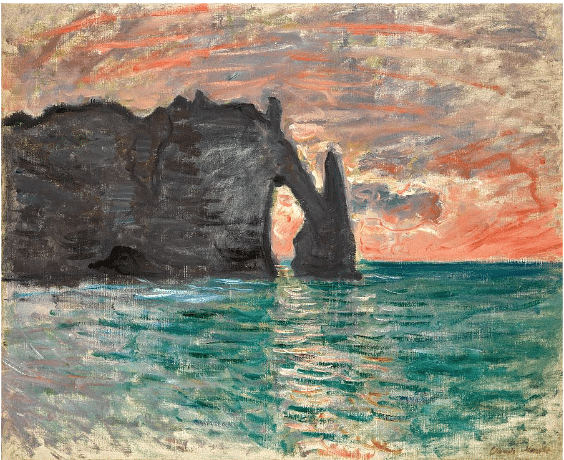

In Monet’s painting (below) of the Manneporte, the sunlight striking the stone has a dematerializing effect that helped the artist to interpret the cliff almost exclusively in terms of color and luminosity.

Claude Monet, “The Manneporte,” 1883

Most nineteenth century visitors were attracted to the rock as a natural wonder. Monet instead concentrated on his own changing perception of it from various angles at different times of day. Doing so brings home the idea that the Impressionists were not painting things and landscapes; they were painting the colors in the light reflecting and the shadows falling upon them.

They were also experimenting with new ways of laying on paint. The characteristic bits and daubs of paint resulted from the theory of “broken color,” which said if colors could mix in the eye rather than on the palette, they’d be more vivid and truer to life. The manner lent a new freshness and authenticity to the painting process. It also, by liberating paint from its function as a purely descriptive, paved the way for modernism and, eventually, abstraction.

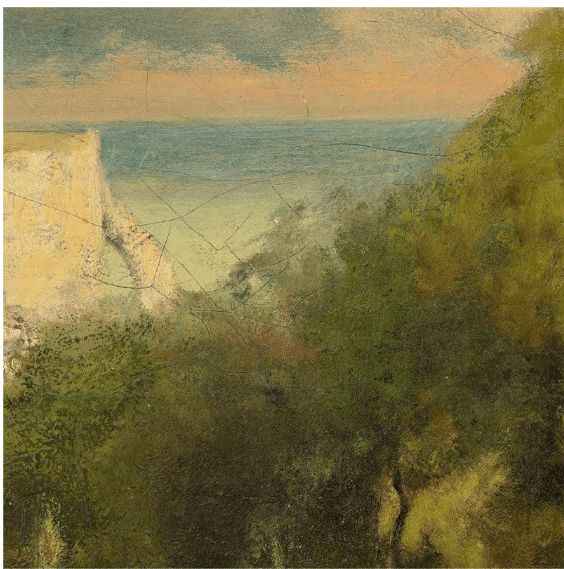

Detail, Claude Monet, The Manneporte, 1883

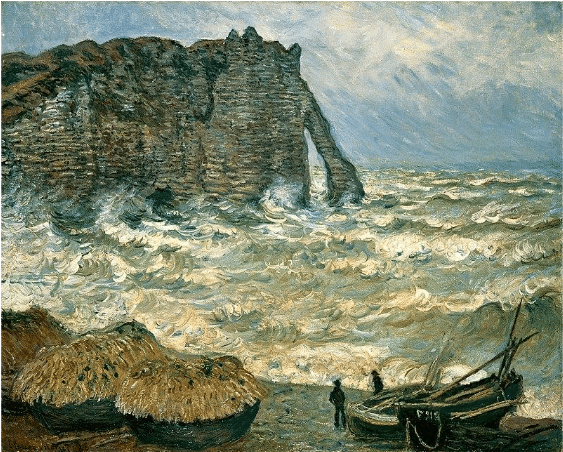

For this view, art historians believe Monet positioned his easel facing west to take advantage of the low illumination of the setting sun. The “frigid” palette and thick brush strokes that describe the motion of the choppy waters have been said to “evoke the physical discomfort posed by the challenge of plain air painting in winter.”

In another rendering of the same location titled “The Manneporte Near Étretat” (1886), Monet flipped the orientation and refined the liquid light of the sea and sky with a calmer and still more luminous patterning of waves and reflections. Perhaps painted late in the day, as the sun began to sink low on the horizon, the cliff reflects pink light that also suffuses the sky and the sea, making it seem as if the whole scene is lit from within.

“The Manneporte Near Étretat” (1886)

Monet painted the dramatically arched projection in the cliff at Étretat six times from this angle: twice during each of three visits to the Normandy coast in 1883, 1885, and 1886. He refined the pictures in his studio.

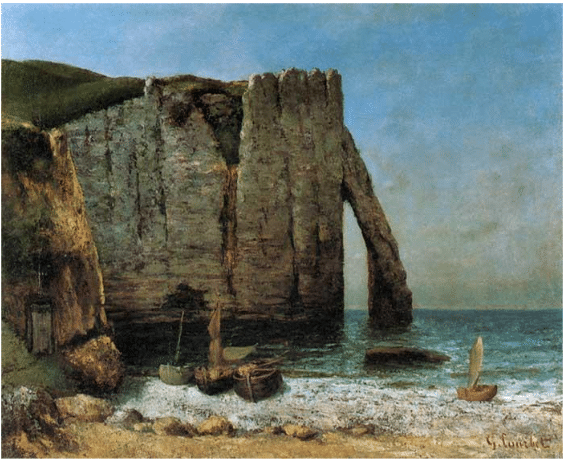

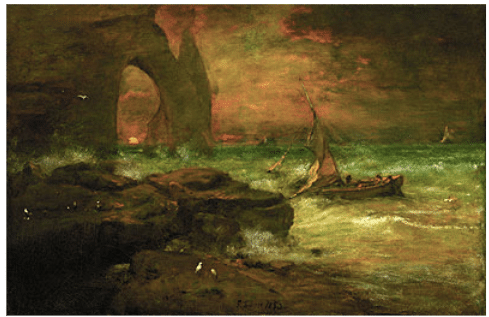

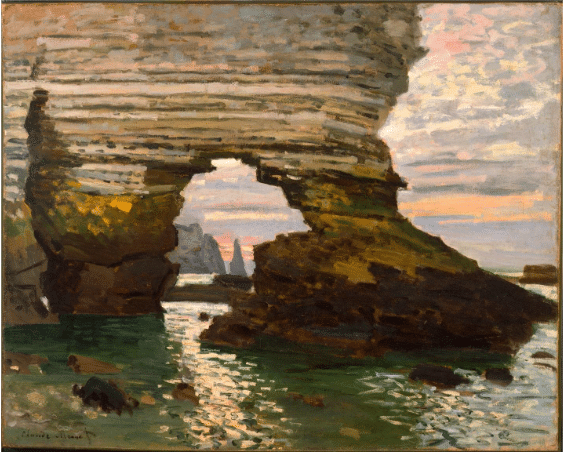

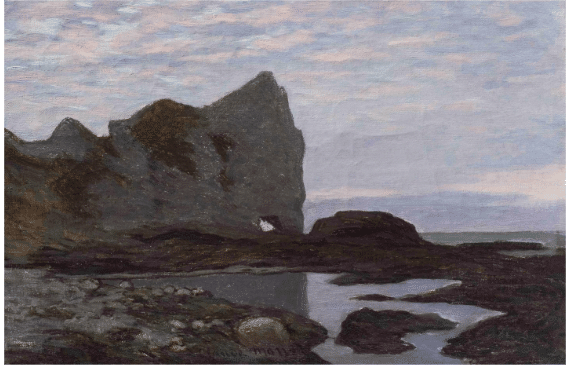

Monet was far from the first or the last to paint the famous cliffs. Gustave Courbet did so in 1870, and American painter George Inness made numerous paintings of the site between the 1870s and 1890s.

Gustave Courbet, Cliffs At Étretat, 1870

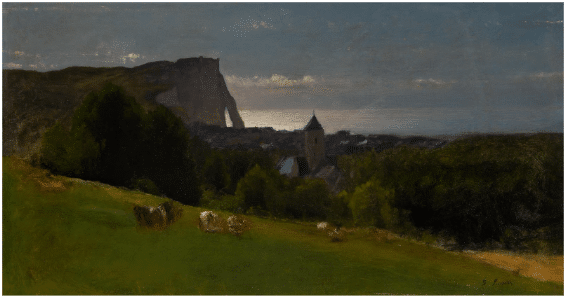

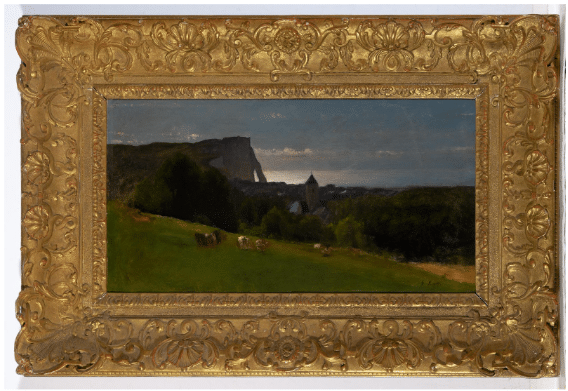

George Inness American, 1825-1894 Étretat, Normandy, circa 1874 14 x 26 1/8 inches

Inness wasn’t interested in painting the light like the Impressionists, whom he did not respect. His approach (which was original to him though today we’d call it tonalist) emphasizes the moody strangeness or almost magical, dream-like quality of the site instead.

Here’s how that painting looked when it was sold at auction in its original frame in 2022.

George Inness, Hillside at Étretat, c. 1874

Inness’s Étretat, 1890s.

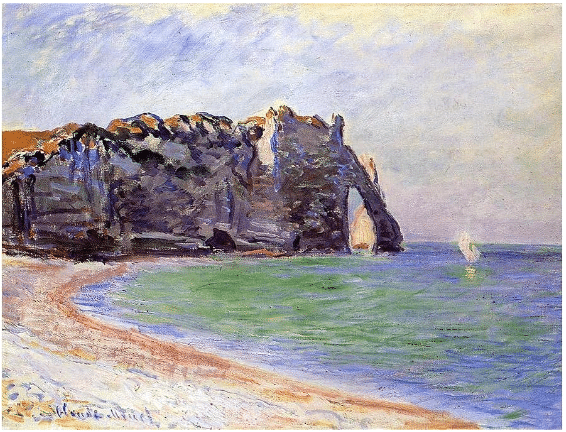

We’ll leave it there and fill the rest of this issue with the beauty of Monet’s Étretat cliff canvases. Titles and years aren’t given because there’s no point to be made here – just a treat for the eyes and imagination as summer in America begins to wane.

Claude Monet, Étretat. 1880s.

Claude Monet, Étretat. 1880s.

Claude Monet, Étretat. 1880s.

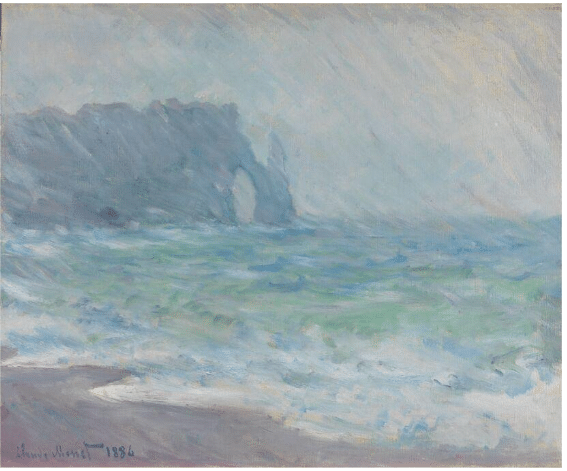

Claude Monet, Étretat in the rain. 1880s.

Claude Monet, Étretat. 1880s.

Claude Monet, Étretat. 1880s.

Claude Monet, Étretat. 1880s.

Claude Monet, Étretat. 1880s.

Claude Monet, Étretat. 1880s.

Claude Monet, Étretat. 1880s.

Claude Monet, Étretat. 1880s.

Antique postcard of the site (presumably at low tide).

If Impressionism is your jam, you may want to look into the professional videos by contemporary masters of the style. Browse them here.