“No situation in the world could be more sad and eerie than this—as the only spark of life in the wide realm of death, a lonely center in a lonely circle…” wrote an early admirer of this painting. “Since in its monotony and boundlessness it has no foreground except the frame, when viewing it, it is as if one’s eyelids had been cut away.”

Critics have described The Monk By the Sea, painted between 1808 and 1810, as “perhaps the first ‘abstract’ painting in a very modern sense” because of its radical composition. Friedrich purposely left out the conventional devices that painters of the day used to create depth.

For example, without a repoussoir — a framing device, such as a tree to the right or left that establishes scale and leads the viewer’s gaze into the image — the emptiness of the foreground disrupts our relationship to the pictorial space. Friedrich has opened a void beyond and between the figure of the monk and the viewer. He cuts the monk off from us spatially and existentially, and there are no traditional landscape elements that might soften the effect.

The tiny figure of the monk (simultaneously a symbol of the spiritual inner life, a self-portrait of the artist, and a stand-in for the viewer) is dwarfed by three different kinds of voids, earth, sea, and sky: the pallid grassless foreground, the iron-black bar of the sea below an inky troubled horizon that shuts down the middle, and the amorphous expanse of vastness that is the sky which occupies the majority of the painting.

In June 1809, the wife of one of Friedrich’s painter friends saw it while visiting him. She later wrote in a letter how “shriveling” she felt the loneliness of the setting to be, deploring the lack of consolation that a little more content – some sort of movement or narrative – might have brought to the painting’s “unending space of air.” Friedrich wants the viewer to feel confronted by the question of mankind coming up against a vast and quite possibly “empty” universe.

After a fairly successful career, Fridrich fell out of favor. Misunderstood and all but rejected by his contemporaries, Friedrich would die obscure and half-mad, gloomy and suspicious of those closest to him. It would take the arrival of the twentieth century’s more existential age for his work to be revered for the magnificent achievement that it is.

This pivotal painting has been compared to many other more or less abstract works by artists including Whistler, Courbet, and perhaps most significantly for our appreciation of a still often misunderstood artist of our own time, abstract expressionist Mark Rothko.

James MacNeil Whistler, Harmony in Blue and Silver, Trouviille, 1845

Rothko (1961)

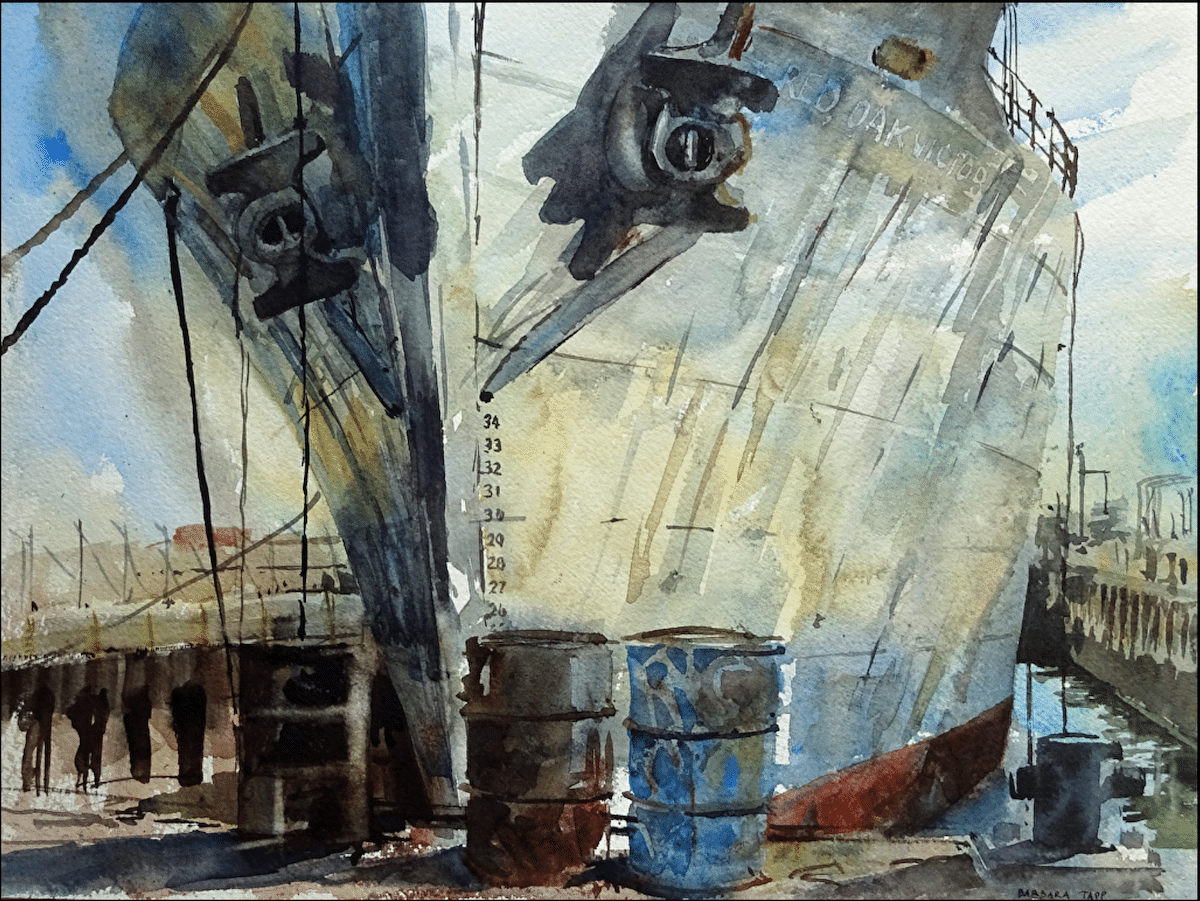

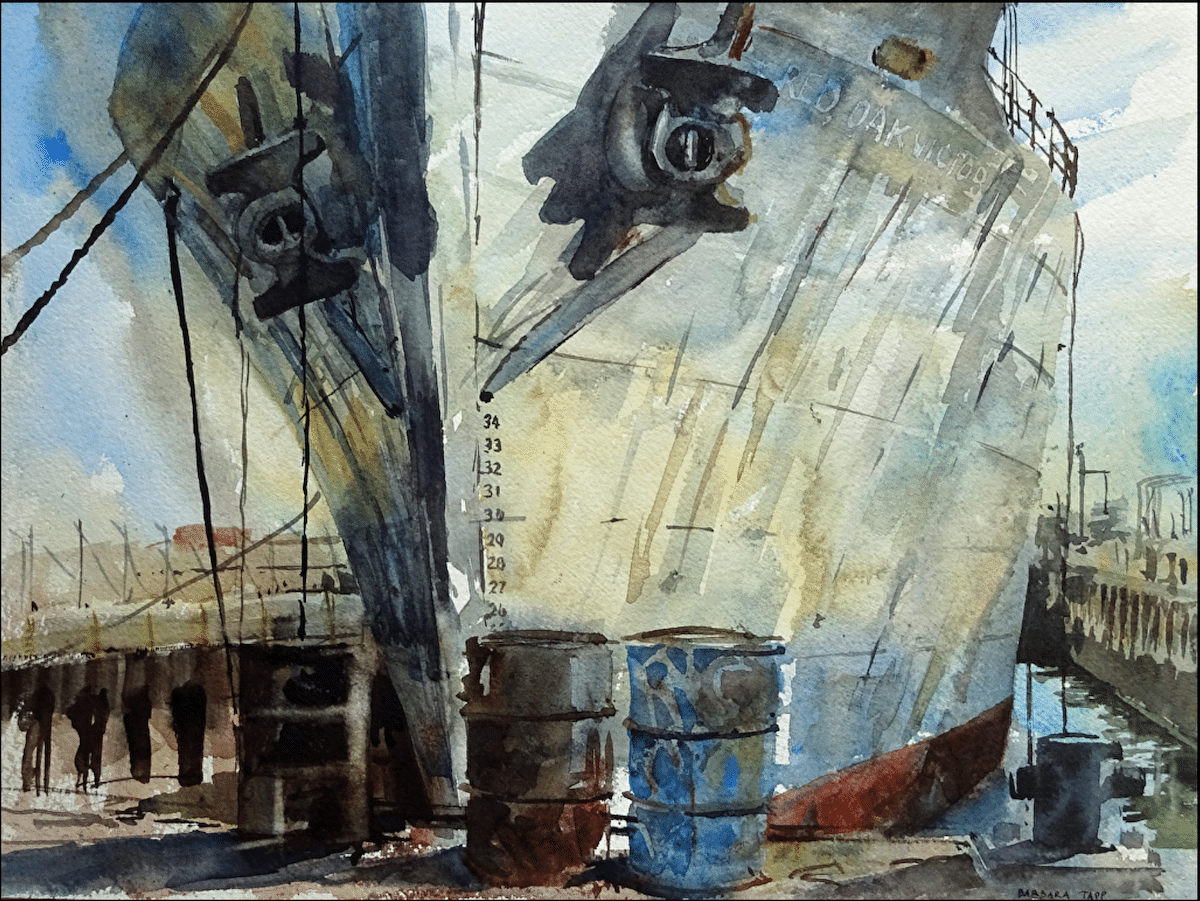

Anchors Away

Barbara Tapp, Anchors, 12×16, plein air watercolor

Barbara Tapp paints plein-air watercolors of scenes and places the intrigue her as she gets to know them better. Of this painting, one of a series of nearly a dozen, the artist writes: “The ship is part of the Rosie the Riveter National Park in Point Richmond, California and undergoing a volunteer based restoration. Recently the engineers fired up the boilers to much fanfare. There is never a dull moment when I am down there painting.”

Barbara Tapp is one of nearly 60 instructors offering workshops at this year’s PACE Plein Air Convention & Expo.