“Businesslike while painting, sure of her technique, she ignored criticism, praise, changes in the art world, and demands of society; she called her art and its accompanying research ‘great fun.'” – Florence Woolsey Hazzar

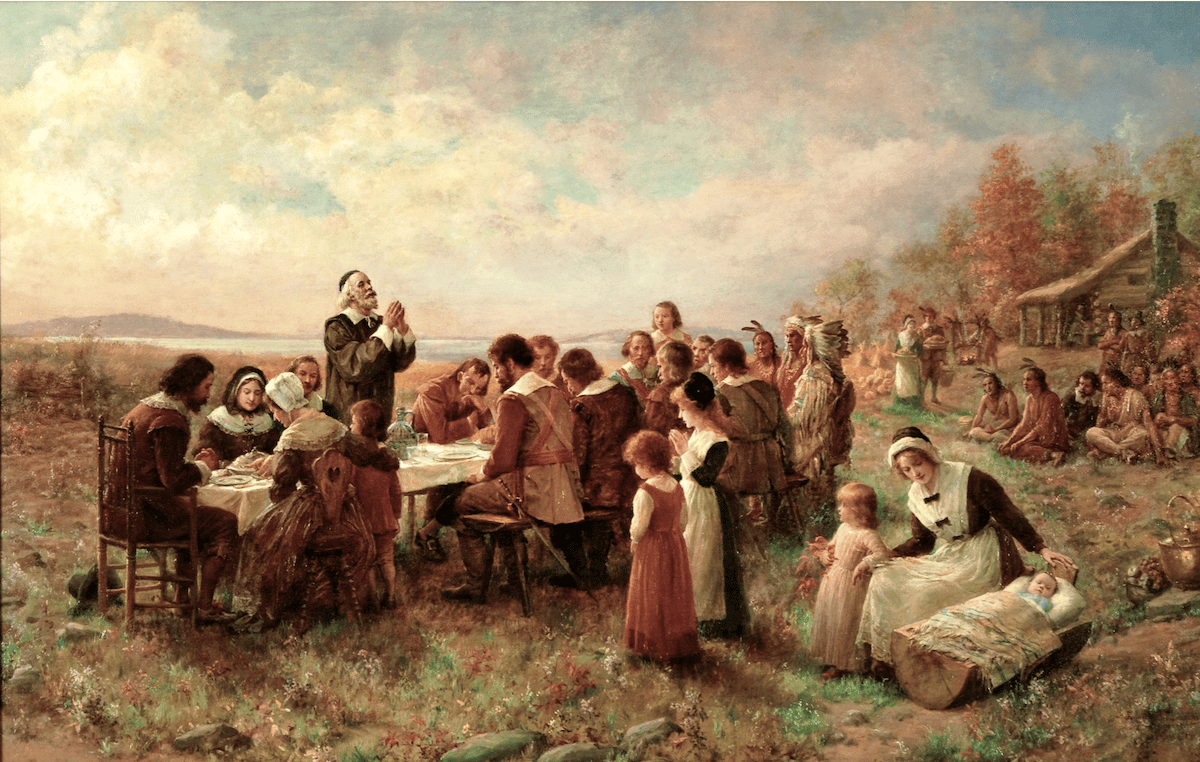

The painting popularly known as “The First Thanksgiving” might or might not be the first one – there are two similar paintings, and they’re often mistaken for each other. Both were painted by enterprising female illustrator and artist Jennie Augusta Brownscombe (1850-1936), and both reflect varying degrees of accuracy and idealization.

Brownscombe was a crowd-pleaser, rendering scenes from colonial American history for patrons who sought nostalgic escape from the increasing urbanization, industrialization, and immigration (i.e. reality) around them. The first version, officially titled “The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth” (1914), hangs in the Museum De Lakenhalin Leiden, South Holland, Netherlands.

Patrons and critics of the day viewed it as true to life despite some verifiable historical inaccuracies (the log cabin and Sioux Indians of the western plains). Historical records affirm that the Pilgrims and Wampanoag Indians indeed shared an autumn feast celebrating the colonists’ first successful harvest in 1621. Brownscombe’s idealized version of the story played to the mainstream vision of the event that was codified during the last quarter of the 19th century.

Perhaps wanting a “First Thanksgiving” that could be viewed on American soil, she reprised the theme in a second version in 1925. Titled Thanksgiving at Plymouth, this version omits the inaccurate Plains Indian headdresses.

Whereas in the first version a praying Pilgrim (Miles Standish, perhaps), acts as focal point (head, bathed in light, rises prominently above the horizon line), in the second the spotlight shifts to the scene playing out in the foreground, where a young mother surrounded by children rocks an infant tucked into a crib.

Jennie Augusta Brownscombe, Thanksgiving at Plymouth, 1925; Oil on canvas, 30 x 39 1/8 in.; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

Brownscombe painted until 1934 when she was 84 years of age. She died August 5, 1936, and is buried in Bayside, New York.

————-

Henry Ossawa Turner’s Quiet Realism

A n0-less moving, though far less idealistic ceremony of thanksgiving appears in The Thankful Poor, by Henry Ossawa Tanner (June 21, 1859 – May 25, 1937). It pictures two African-Americans, presumably a father and a son, praying at a modestly laid table.

Tanner taps into the tradition of genre paintings of the poor by the 19th-century Dutch and French Realists to suggest the hard realities of African-American life, the racial discrimination and injustice that were then, and still are, commonplace in America.

Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Grateful Poor, 1898

Tanner was an American artist and the first African-American artist to achieve international acclaim. He studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. There he was a favorite of the master painter Thomas Eakins (who painted his portrait) and made important connections with influential artists such as Robert Henri and others.

Tanner moved to Europe and studied at the Academie Julian in Paris, where his work won a third place medal in the 1897 Salon. In 1923, the French government awarded him the prestigious Legion of Honor.

Thomas Eakins, Portrait of Henry Ossawa Tanner

Although Tanner gained confidence and recognition for his work, he always faced racism working as a professional artist. In his autobiography, The Story of an Artist’s Life, Tanner described it this way:

“I was extremely timid and to be made to feel that I was not wanted, although in a place where I had every right to be, even months afterwards caused me sometimes weeks of pain. Every time any one of these disagreeable incidents came into my mind, my heart sank, and I was anew tortured by the thought of what I had endured, almost as much as the incident itself.”