The Pre-Raphaelites were a British circle of nineteenth century artists who passionately believed art had lost its important devotional function as a conveyor of sacred beauty and timeless truths. They chose their name, which means before Raphael, because many saw the painter Raphael as emblematic of the Italian Renaissance, the fifteenth-century “rebirth” of interest in classical humanism, which shifted painting’s primary function from the religious to the humanistic.

The Pre-Raphaelite artists practiced an art that lifted up the identity-defining literature of the British Isles, such as English myth and poetry and the historical legends of King Arthur and his court.

Several found inspiration in a poem called Isabella, or the Pot of Basil by the English poet John Keats. The poem itself was inspired by Boccaccio’s fourteenth-century pseudo-mythological Decameron (kind of an Italian equivalent of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales). Hence the paintings’ medieval imagery.

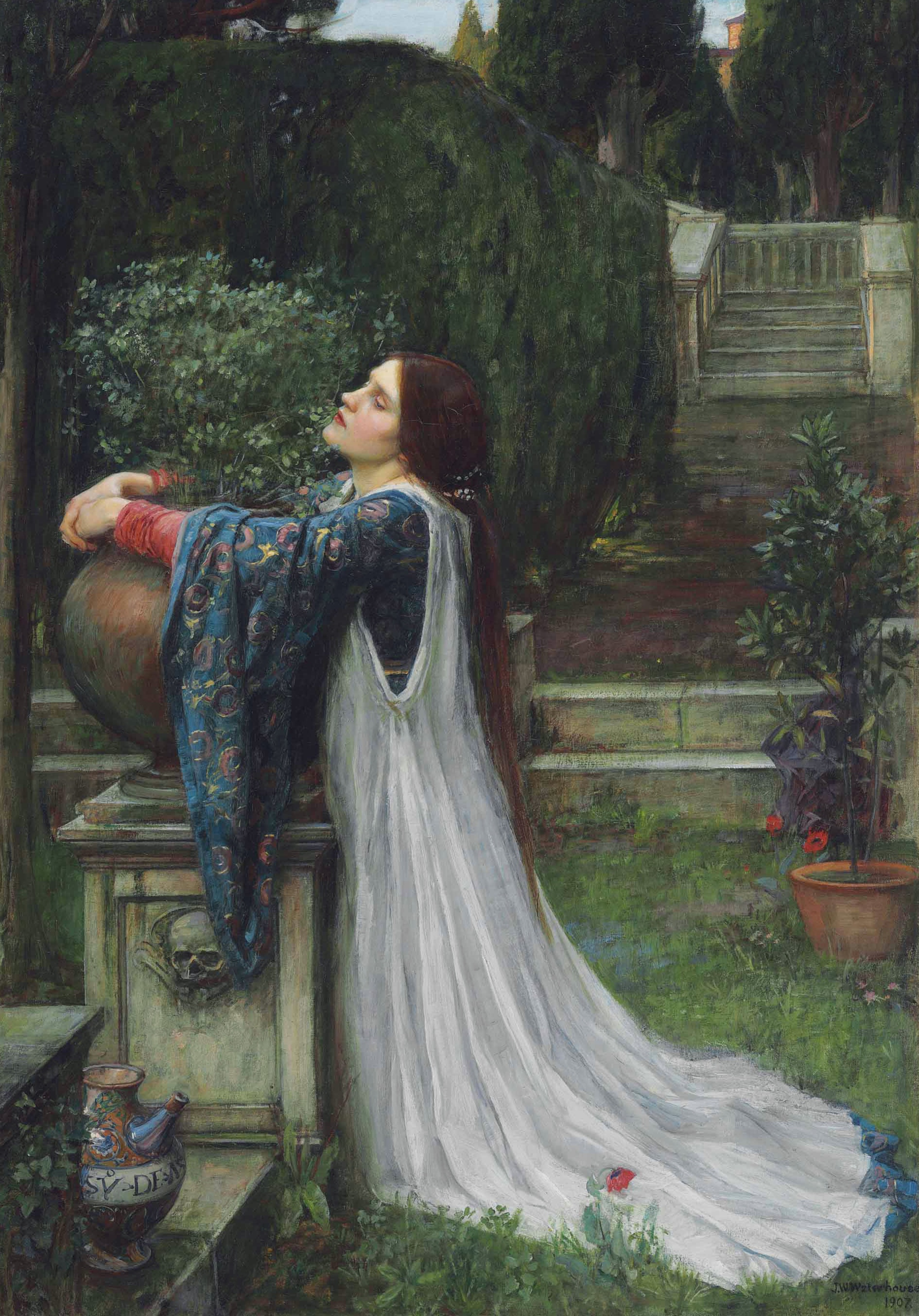

John William Waterhouse, Isabella and the Pot of Basil, 1907. license

Waterhouse gives us a straightforward depiction that matches the story. In Keats’ poem, a young woman named Isabella rebels against her scheming family’s plans to marry her to “some high noble and his olive trees.” She confesses her love for one of the family’s servants, a man called Lorenzo, whom her brothers then murder to prevent the unprofitable match.

John Everett Millais, Isabella, 1849

In this version by Millais, we see the situation before the tragic events unfold. One of the brothers is trying to kick a dog (a stand-in for Lorenzo) that’s devotedly resting its head on Isabella’s lap, while the others at the family table betray no emotion but stoic, self-absorbed indifference. The servant, Lorenzo, offers a blood orange (symbolic of passion) to Isabella, who reaches for it with eyes closed, as if in going through the motions of a recurring dream. Her lover Lorenzo’s intense, adoring gaze says it all. The story is told through metaphor, facial expressions, and body language. Millais further encodes the narrative in the symbolic details of a hawk tearing at a feather on the extreme left, the carving on Isabella’s chair, (an execution? also PRB stood for Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood) and the passionflower above her head.

After his murder, Lorenzo’s ghost visits Isabella in a dream and informs her of the brothers’ deed and where they buried him. Isabella exhumes the body and conceals her lover’s head in a pot of basil which she takes care of obsessively, pining away with sorrow for her loss. Once-fair Isabella, so Keats’ poem reads: … forgot the stars, the moon, and sun / She had no knowledge when the day was done …

And the new morn she saw not: but in peace

Hung over her sweet Basil evermore

And moistened it with tears unto the core.

As her tears nourished the plant, it “flourish’d, as by magic touch,” Keats writes, even as Isabella’s strength and life ebb steadily away. Finally her brothers suspect, steal the garden-pot, find the head, and hide it away from her, which spells the end for Isabella:

And so she pined, and so she died forlorn,

Imploring for her Basil to the last.

No heart was there in Florence but did mourn

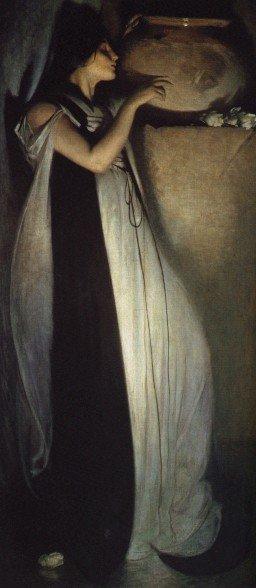

English painter John White Alexander, in his painting Isabella, relies less than the other artists we’ve looked at on literal narrative elements and rather explores the mood of the piece through the poetry of design, tonal color, and shading.

John White Alexander, Isabella, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (how did Isabella Stuart Gardner not end up with this painting??)

It’s a remarkable composition, almost a visible analogue of mourning; at the top of the half-lit painting, Alexander concentrates all of the descriptive elements of the lady “hanging” on the garden-pot, while the whole rest of the painting is given over to this massive, flowing monochromatic river of black under pale billowing garments resembling the cerements of the grave. A more “poetic” painting one can hardly imagine.

William Holman Hunt, Isabella and the Pot of Basil, 1867

In contrast, William Holman Hunt, in his ornate, well-balanced and highly detailed depiction, shows the poem’s heroine with her head resting lovingly on the pot of basil; the ornamentation at its base includes a skull (as did Waterhouse, our first example). It is said that Hunt modeled his version of Isabella on his wife Fanny’s likeness, who had recently died from a fever. Cut flowers and torn petals scatter at her feet.

Ah, the Tragic Romance of it all! Poor Keats, the quintessential Romantic poet, was himself among the “dusty trophies hung” upon the trophy wall of Dame Melancholy. The poet’s one great love, Fanny Howe, refused his advances. He penned the story of Isabella’s unrequited love in verse three years before tuberculosis cut short his own sad life at the age of 25.

Search On for Missing “Jaws” Painting

Jaws audiobook cover. Source: screenshot Googleplay

Who doesn’t know the “Jaws image” – the iconic book cover and movie-poster painting of a monstrous great white shark torpedoing upward toward an oblivious woman swimming on the surface? The image absolutely caught the thrust of the story and surely didn’t hurt the movie’s box office success (it was bl0ck-buster director Stephen Spielberg’s first film and launched his illustrious career).

The painting is arguably as recognizable as any other among American culture, be it Warhol’s Marilyn, Munch’s The Scream or the Mona Lisa. But you can’t go see it in a museum; it’s been missing since 1976.

The artist, Roger Kastel, is now 91, still painting away, and reportedly not bitter about the theft, according to the artist’s son. Matthew Kastel recently penned something of an open letter to greater Hollywood asking if anyone’s seen it (or at least willing to apologize for losing it).

The painting went missing just after winning an award (which also never made it back to the artist). According to the artist’s son, unfortunately it’s not unusual for illustrations for Hollywood properties to go missing. And as for hunting down Jaws painting? Let’s just say he’s gonna need a bigger boat.

“Where is one to start on a mystery over 45 years old with no clues?” writes his son Matthew. “Outside of putting my father’s Jaws illustration on the back of milk cartons under the caption MISSING, I have no clue.”

“Was the painting simply lost, misplaced, or thrown away like an old movie prop by Universal out of lack of care or ignorance? Or was it stolen somewhere in Universal’s care by an admirer and/or enterprising thief?”

“My recourse is limited. By writing this article, I am taking a longshot approach that someone out there reading this may know about its whereabouts or fate and step forward.”

If see something (especially a large, gray, fast-moving fin!), say something!

In the Paint,

– Chris