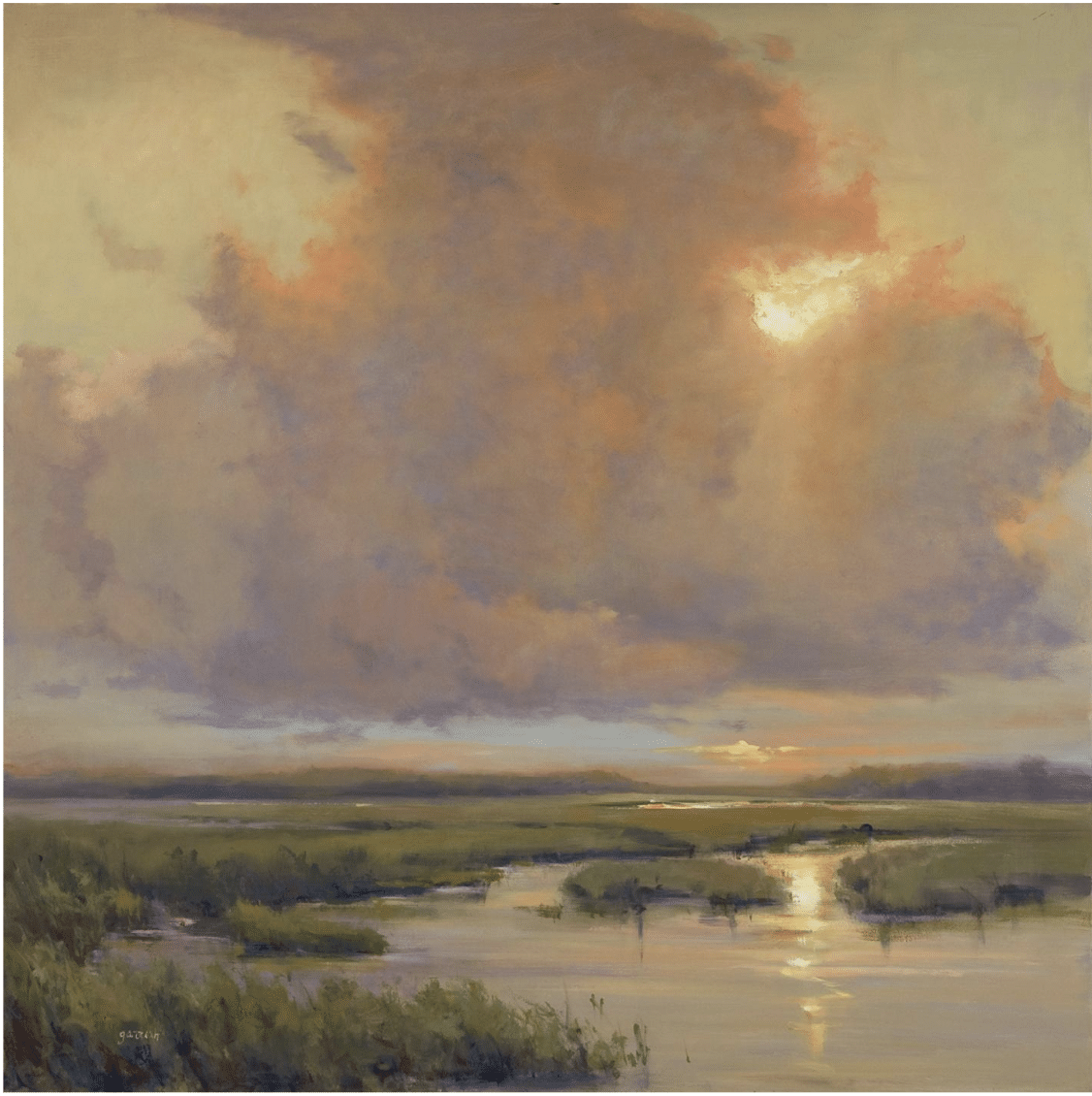

Not sure whether to paint a seascape or a landscape? Try a marsh! Marshes combine the colors and skies of landscape with the light effects of water. They’re a great subject for a painting in any medium, as long as you know how to handle the sky and the sometimes jigsaw-like terrain.

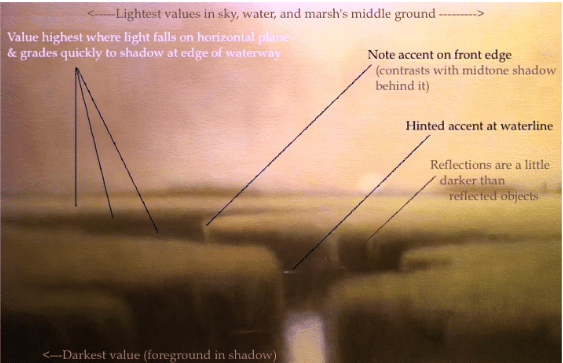

As you can see in the diagram below, in marsh paintings, highlights and shadows are particularly important. Light falls on the horizontal patches of grass and quickly blends into shadows on the vertical sides which darken the deeper they go. Reflections require blending and blurring, but it’s the relationship between the reflection and the overlapping patches of grass that convince the viewer. Think of the vertical reflections and gaps between light and shadow as ways to break up the natural horizontality of these flat spaces.

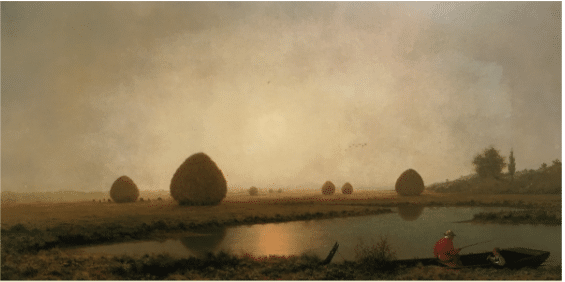

Nineteenth-century painter Martin Johnson Heade (1819-1904) loved painting New England salt marshes. One of his favorite spots was in Newburyport, Mass. The grasses hayed from these locales had a high salt content that cattle loved. Heade took advantage of the large stacks of harvested marsh grass to break up his strongly horizontal compositions.

The horizontality of the marshes, for Head and for anyone painting today, allow full breadth to explore skies and atmosphere.

Martin Johnson Heade, Sunset over the Marshes, 1890-1904

Heade painted his marshes as much for their moods as for their light, colors, and shapes. Heade alongside many marsh painters since follow the Dutch landscape formula: big skies full of drama (including vertical and diagonal elements) and a relatively low horizon line.

Martin Johnson Heade, Sunrise on the Marshes, c. 1875

Heade’s marshes are far more than records of place – marshes then were utilitarian haying and grazing areas, even more mundane and ordinary than they seem to us now. By the standards of the grandiose Hudson River School, they were flat, both literally and figuratively, lacking in dramatic mountains or vast timeless distances.

And that’s exactly why Heade chose them – if he was going to paint a worthwhile marsh, it would be because of what he put into it rather than only what was there. Novelist John Updike has written about Heade’s “calm,” in which he finds something universal that speaks to our own time:

“Heade’s calm is unsteady, storm-stirred; we respond in our era to its hint of the nervous and the fearful. His weather is interior weather, in a sense, and he perhaps was, if far from the first to attempt portraits of human moods in aspects of nature, the first to portray a modern mood, an ambivalent mood tinged with dread and yet imbued with a certain lightness.”

Martin Johnson Heade, Newburyport Marshes, c 1871

“The mood could even be said to be religious: not an aggressive preachment of God’s grandeur but a kind of Zen poise and acceptance, represented by the small sedentary or plodding foreground figures that appear uncannily at peace as the clouds blacken and the lightning flashes.” (John Updike, Still Looking, Essays on American Art, p. 55)”

May the lightning of inspiration strike while you too stand ankle-deep in mud, swatting mosquitoes away from your ears and eyes as you capture a moody marsh or two on canvas of your own.

In her downloadable video, Mary Garrish demonstrates a marsh painting that is more than just how to paint a marsh: it’s a full course in the elements of design and composition by which any painting lives or dies. Download it now.