“Don’t just paint it, paint it doing something.” – Charles Woodbury

American painter and renowned teacher Charles Woodbury (1854-1940) advised his students in his revolutionary turn-of-the-century classes to “paint in verbs not in nouns.”

Woodbury, whose outdoor art school became a cornerstone of the Ogunquit, Maine summer art colony, wanted his students to enter into the life of the things they painted. He wanted to inspire them to fresh, “active” seeing and expressive creativity. “You don’t draw what you see of the wave – you draw what it does!” he would tell his students.

The implication is that painting is perceptual – realism is a record of the felt and the seen (not just of what’s visible, as to a camera). For artists, reality is “participatory” – that is, we play a part in how we perceive what we look at, Woodbury would say, and as painters we get to cultivate that quality of mind.

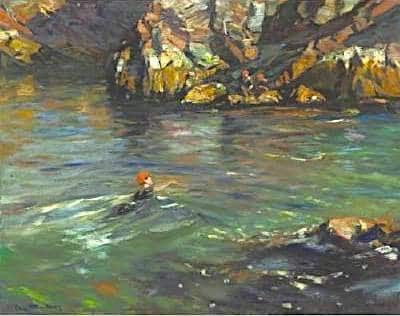

Charles Woodbury, The Swimmer

“Realism is not based on the way things are, but upon things as you see and feel them,” Woodbury said. “Realism is after all only what you think the thing may be.”

Given the fluidity of painting and perception, Woodbury championed art-making as a mechanism for seeing more and better, a powerful tool for recognizing not only what and how we truly think and see, but what we hold dear as well.

To Woodbury, the “Life Force” was the most important thing. It didn’t matter whether he was painting a mountain, a wave, a beach, or a patch of rhododendrons – for him, paintings showed the evidence of universal life energy at work in whatever particular subject before him.

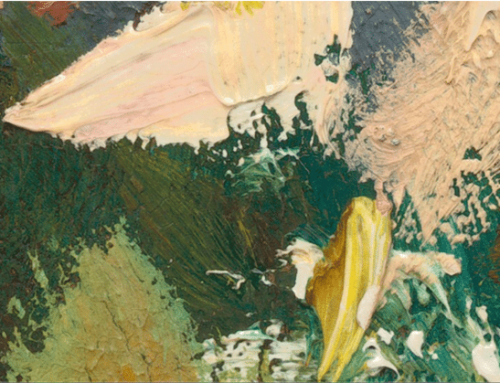

Look, for example, how in Woodbury’s painting Rhododendrons (below) the brushwork sets everything in motion – ragged treetops vibrate against a sky full of brushy, multi-directional clouds; the flower petals toss this way and that, as if straining to take off into the air; the foreground earth ripples and rolls. It is a landscape painted fully in service to life in motion, to growing – to life itself.

Charles Woodbury, Rhododendrons, oil, 29″ x 36″ c. 1930

Painters make choices about what to put into a painting and what to leave out. They also make choices about how expressively vs. how “accurately” they paint what they choose to put in. You can paint a dazzlingly accurate rocky hill and you can paint an “edited” rocky hill or you can paint an imaginative rocky hill and an abstracted rocky hill. Neither approach is necessarily better than the other. It’s what the artist puts into it that matters.

Woodbury favored an imaginative, participatory approach. He would advise, even about rocky hillsides, not just to paint it but to paint it doing something. You can read more about him here.

Nicolas Coleman’s sunset and still water form the backdrop for the “story” of the canoeist leaning over his campfire on the outcropping were he prepares to spend the night.

Nicolas Coleman’s “story telling” paintings are a way to “paint it doing something” and thereby activate the viewer’s interest and imagination. Coleman demonstrates and speaks about his approach in his video, Visual Storytelling, Creating Emotion with Your Brush.

Dutch Master Drawings Discovered |

By Kelly Kane

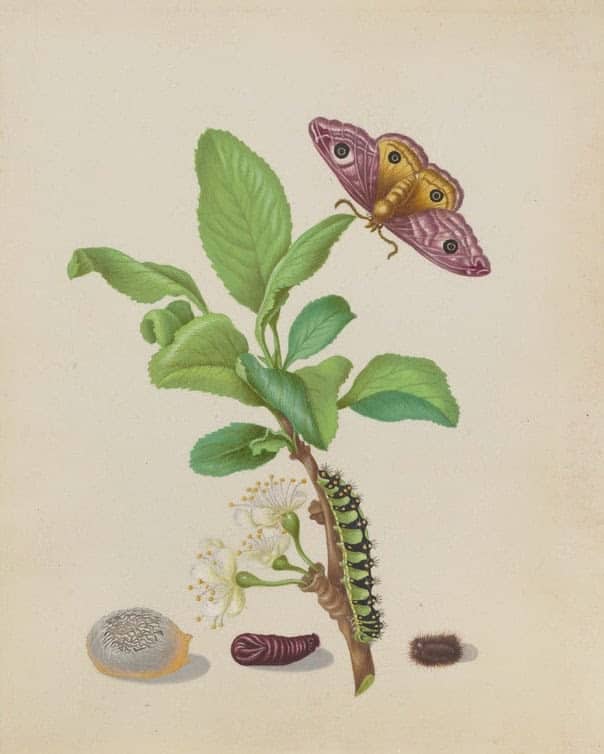

“Metamorphosis of a Small Emperor Moth on a Damson Plum” (Plate 13 of The Caterpillar Book), 1679. Maria Sibylla Merian (German, active in the Netherlands, 1647-1717). Watercolor and opaque watercolor over counterproof print on parchmant. 18.7 × 14.9 cm (7 3/8 × 5 7/8 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles The J. Paul Getty Museum is presenting “Dutch Drawings from a Collector’s Cabinet,” an exhibition showcasing for the first time a magnificent group of 17th-century drawings acquired from a private collector in 2019. On view through January 15, 2023, the exhibition features 50 works in a variety of media by artists from the Dutch Republic, including Rembrandt van Rijn, Adriaen van de Velde, Jacob van Ruisdael, and Aelbert Cuyp, among others.Five botanical drawings in the exhibition demonstrate the fascination with the natural world and the interaction of art and science in the Netherlands. Jacob Marrel’s imposing watercolor, Four Tulips, speaks to “tulipmania,” a period when the speculative prices for tulip bulbs reached astonishing heights before the market collapse in 1637. Maria Sibylla Merian’s watercolor Metamorphosis of a Small Emperor Moth on a Damson Plum is a meticulous rendering of the metamorphosis of an emperor moth from egg to caterpillar based on a counterproof from her Caterpillar Book of 1679. |