The leading visual artists of the early 20th century were not interested in portraying a window onto the world as it had appeared since the Renaissance.

In their work, as in the work of the novelists, photographers, psychologists and philosophers of the period, the world was understood to be filtered and changed by the mind in startling ways. Imagination enhanced and often replaced observational renderings. To quote American poet Wallace Stevens responding to Picasso’s painting, The Old Guitarist, “Things as they are / Are changed upon the blue guitar.”

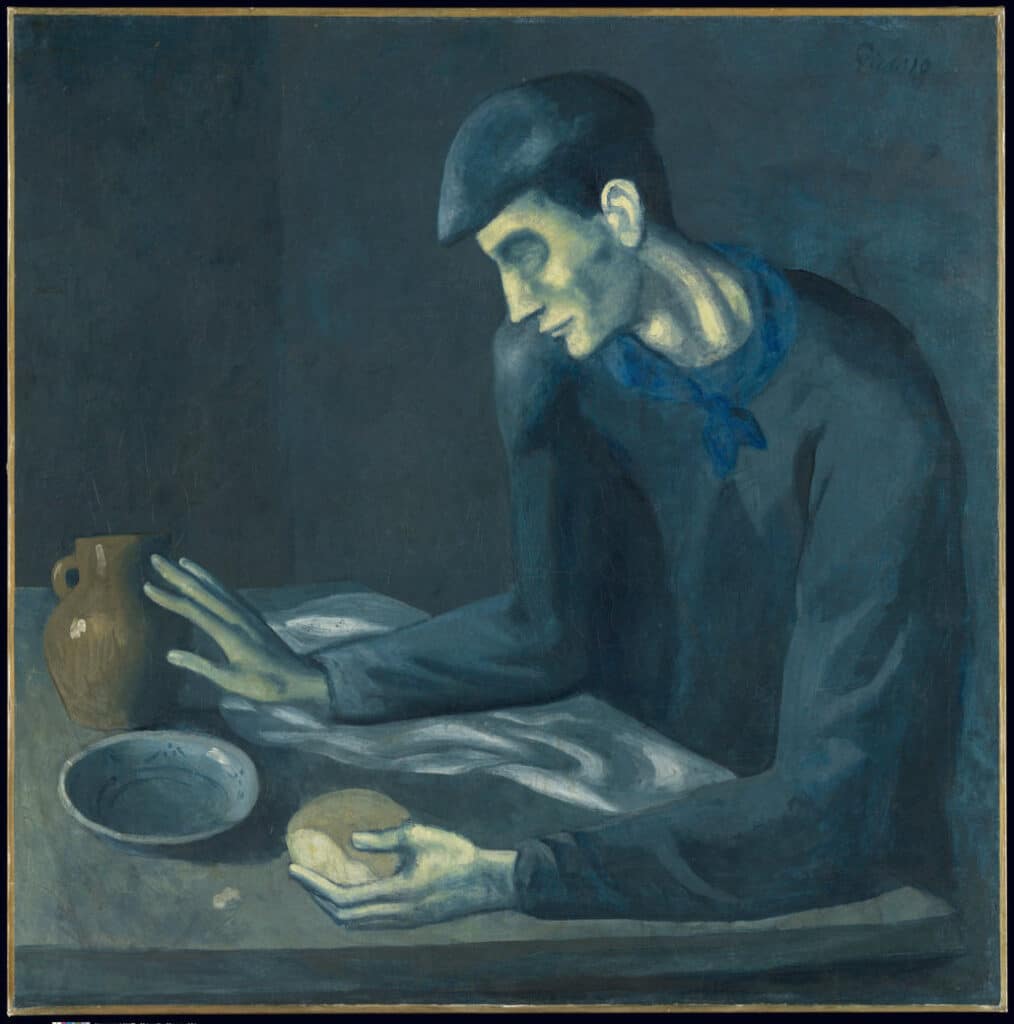

The Old Guitarist belongs to Picasso’s so-called Blue Period, between 1901 and 1904, when he used predominantly Prussian blue in addition to ochre, green and gray pigments to, “cast a melancholy shade on his works,” as Christie’s modern art specialist Allegra Bettini puts it.

Picasso’s direct, non-traditional approach laid a new foundation for what painting could be and do; far from frivolous, the 20 year-old’s work resolutely reflects a sudden plunge into grief and shock.

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) Le Repas de l’aveugle, 1903 Huile sur toile, 95,3 x 94,6 cm New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. 50.188 Photo

Grief over the sudden death of someone very close can suddenly clarify for the survivor what really matters in life and what doesn’t. I think it was that way for the young Picasso when his best friend committed suicide in public. I think he resolved to strain all of his powers of imagination and artistry to do something radically honest and authentic; to allow feeling and creative imagination to dictate every creative choice.

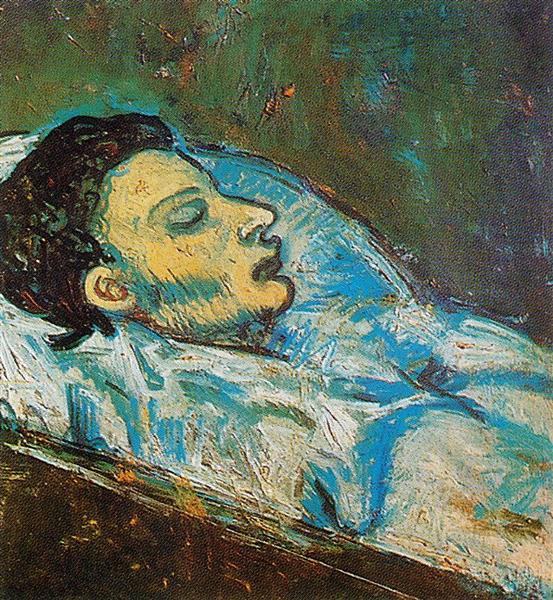

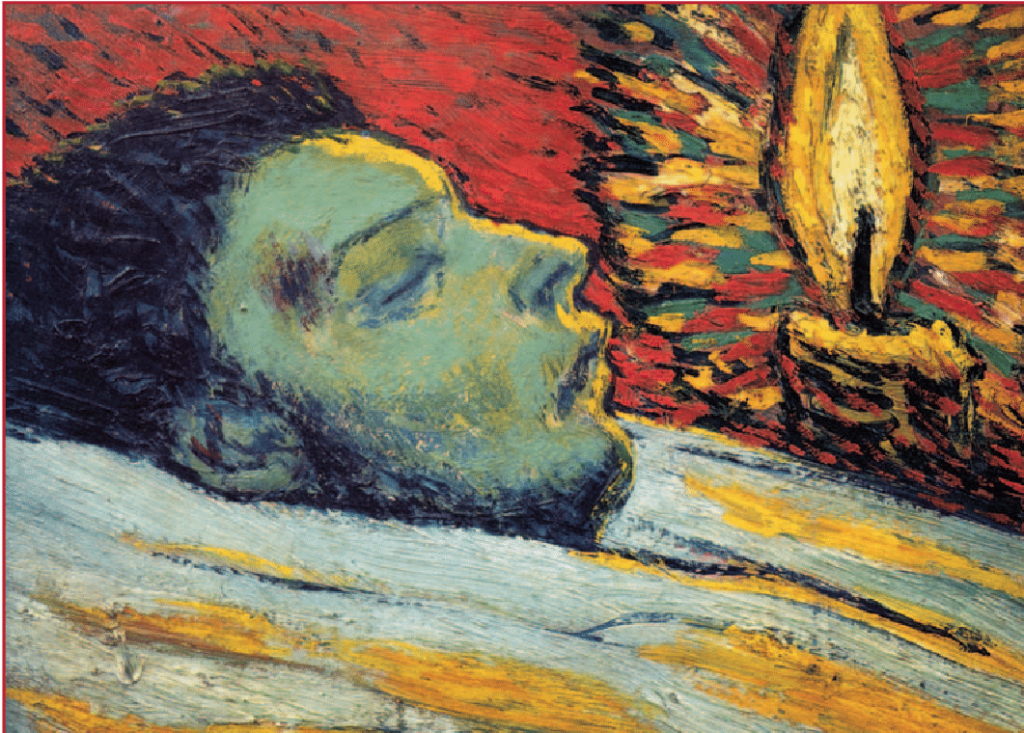

Picasso, La Mort de Casegamas, 1901

Picasso, La Mort de Casegamas, 1901. Picasso in this version of “The Death of Casegama” transforms the naturalistic rendering into a symbolic tableau in which the young poet’s head, floating like the Greek poet Orpheus’ on a fiver of gold and white, is gilded by the radiant warmth of an oversized, fantastical candle-flame, symbolic of the spirit.

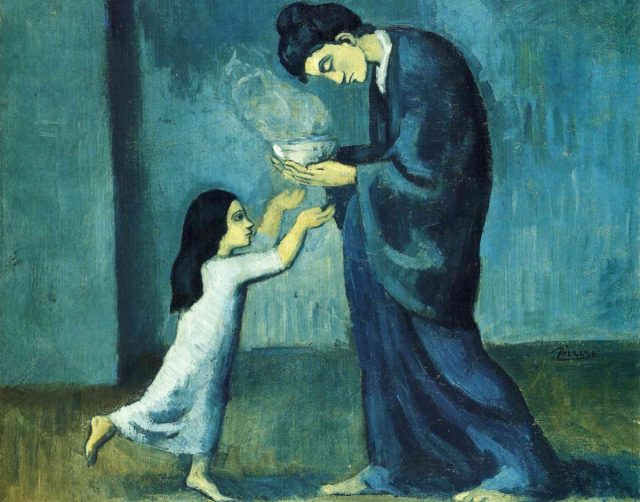

Pablo Picasso, La Soupe (The Soup), like most works from the artist’s blue period, makes extensive use of Prussian blue.

A Painting (and a color) Full of Significance

The Old Guitarist painting has an uncanny power. The way the figure holds the guitar, as if locked with it in an embrace, radiates an almost “Madonna and Child” vibe. Picasso was consciously treating his subjects – cast-offs from society and others living close to the bedrock of life – almost like secular saints.

As for the color, Picasso is using primarily Prussian blue, and at first the painting of the guitar player seems to be more than 90% blue. But look closer and you won’t find more than a few square inches of unbroken blue anywhere; close observation reveals that throughout the entire painting, Picasso offset the Prussian blue’s cold, electric hue with warm orange ochres and grays.

In the image below, the color saturation has been enhanced in a photo-editing program to make it easier to see the many areas and touches of orange, even within the supposedly blue fields of color. As the complementary color of blue, orange creates a contrasting “broken color” effect that everywhere breaks up potential monotony.

Picasso evidently began the painting with a canvas stained with an orange-hued pigment, a warm earth-tone, something like raw umber or sienna, which peeks through the subsequent (blue) layer. Going on color theory that says warm colors advance toward the viewer while relatively cooler ones recede, to the eye the surface of this painting should have something like a visible pulse, a “vibration” that sets in motion and brings to life the otherwise flat fields of color.

Picasso was part of a generation of young artists struggling to survive and make important work without the support of the state or the Academy. To be an avant-garde artist required self-awareness and sacrifice. I had a postcard of this painting when I was a teenager. I saw The Old Guitarist as a strong statement of the independence of art and creativity. As a young artist-writer about same age as when Picasso painted it, I identified with the musician’s bent figure, how he dwells in a rapt inner life despite the cramped, confining space.

Picasso’s painting still speaks to us of the sense of weariness vs. persistence, the democratic comfort of creativity, and the stubborn belief in art and beauty despite the realities of poverty, loneliness, injustice, and time.

As an artist, do you long to take a more personal approach? Do you wish your paintings could tell a clear “story”? In Ann Baldwin’s video, “Telling Stories with Collage and Paint,” the artist goes beyond beginner painting and shows how to use texture and layering techniques along with collage to create a deep and meaningful story. She shares her approach to color, explains her process for directing the eye to the important parts of her design, and discusses the importance of being willing to sacrifice parts for the good of the whole. If you’d like to know how to use texture painting and collage techniques to tell a story, check out Ann’s video here.

Plein Air Convention Ready to Roll

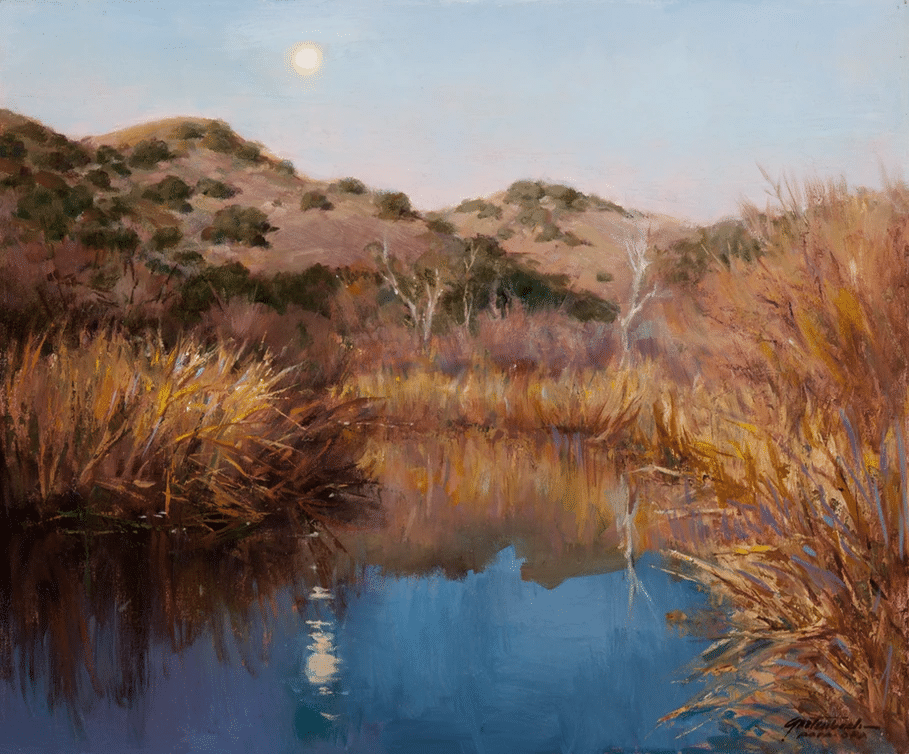

Lynn Gertenbach, Moonrise, Malibu Creek, oil, 20 x 24 inches. Lynn teaches a dynamic plein air approach in her video LYNN GERTENBACH: THE ONE HOUR PLEIN AIR LANDSCAPE.

Every year, hundreds of the world’s most enthusiastic outdoor painters gather at the Plein Air Convention & Expo (PACE) to learn painting techniques from the world’s top artists. They come to see what’s new, what’s hot, and what’s working RIGHT NOW in art marketing. It is the largest gathering of plein air painters on the planet and there is no other event like it. The “Woodstock of plein air” is different every year, yet every year there are artists at PACE who are, or will become, some of the greatest artists of our time… and you get to meet and mingle with them.

Learn more about PACE.