As anyone who spends enough time making art finds out, meaningful creativity demands that we learn about ourselves.

In a recent article by Douglas Fryer published in Inside Art, the artist pointed to a common misconception about painting: that if you want to make a beautiful work of art, you should select a beautiful subject.

Seems logical, but Fryer warned that placing “unbalanced value on the assumed worth of the subject itself” risks leaving out arguably the single most important ingredient of all – the imaginative engagement of the artist. As artists we need to pay attention to what’s true to us.

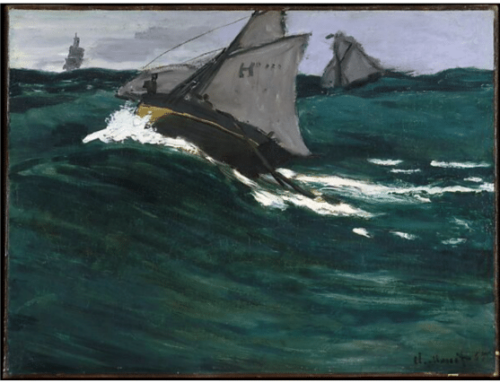

Douglas Fryer, Moonlight on the North Sea, oil, 13″ x 18″

“Technique,” Fryer wrote, “style, effects, ‘proper’ rendering, ‘rules’ of composition – are all ends to which many artists aspire, but as final objectives they fall quite short of the mark. When relying on these elements alone, the work often becomes affected, habitual, and manneristic. On the other hand, a meaningful engagement of the artist with the subject creates dialogue and inspires a search for the method and the materials of invention, and requires an investment of time and emotion.”

We know it when we feel it; as viewers, Fryer said, we “stand before such art almost powerless to resist the honesty and importance of the forms, marks, patterns and colors that make up the composition before us.”

One must master the tools best suited to one’s unique expression. Yet, beyond technique, observation, and any inherent qualities of the subject itself lies the deeper purpose of art – to access the truest parts of ourselves and to foster meaningful shared experiences through the work.

Douglas Fryer, Night Visitors, oil, 17 x 30 inches

Sherrie McGraw: Know Thyself

The artist’s honest, imaginative engagement is what it’s all about. “A visual concept independent of storytelling or literary intent,” says Sherrie McGraw, “lends gravitas and visual delight to a painting and is the real reason a work of art captivates viewers for generations to come.”

“Learning how to paint and draw is possible. While a cloak of mystery surrounds the mythical artist that is often intimidating to the novice, if someone is visually wired, he or she can learn to paint and draw. So why aren’t these disciplines easy? Why do they seem at times so difficult and why are great artists not more prevalent?”

Sherrie McGraw, Chinese Pot and Roses, oil, 12″ x 16″

“Painting and drawing themselves are simple, but there is a reason that in practice, they are not easy. There is the small matter of our own minds. This is the real hurdle that is not broached often enough.”

“Every brushstroke and line we make is filtered through our own perceptions, prejudices and emotional resistance to change. We are each the product of our entire lives and learning to be an artist is really learning about ourselves.”

Sherrie McGraw, Dancing Feet, oil

“And to me the most valuable part of this process is not the product of our labors, it is the richness of deepening self-awareness.”

If you’d like to know more about how Douglas Fryer and Sherrie McGraw create paintings imbued with meaning and vitality, you may wish to look into Douglas’s video Painting with Intuition or Sherrie’s step-by-step still life tutorial, In the Studio with Sherrie McGraw.

Communicating the ‘Character of Place’ in Paint |

|

|

|

| “Terlingua Trading Post Vista” (watercolor, 10 x 14 in.) | |

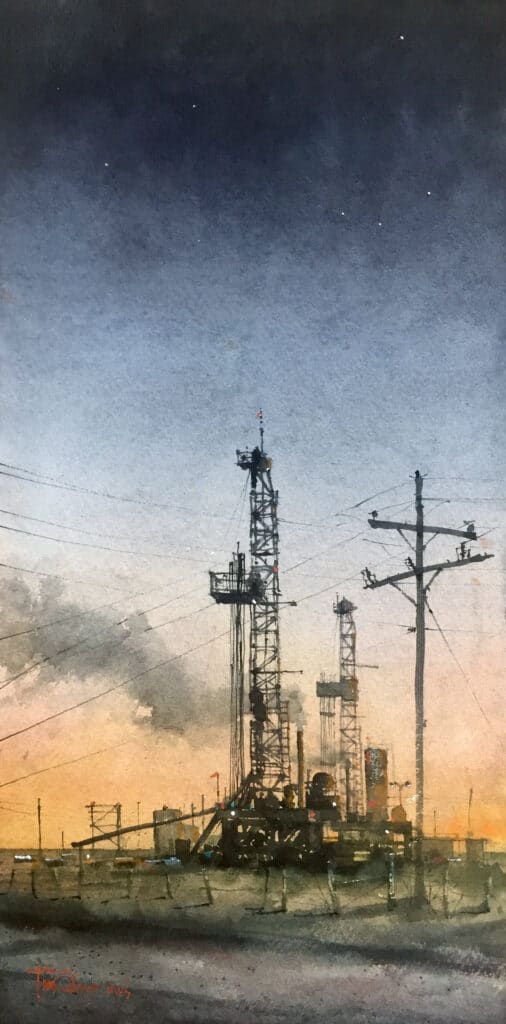

Kelly Kane: How do you feel your day job in landscape architecture impacts your plein air work? What are the sensibilities that crossover? Tim Oliver: Being in a design profession, I’m accustomed to drawing and sketching, so I’ve always felt very comfortable communicating graphically with a pencil and paper. I think I was actually drawn to landscape architecture for the graphic component of the job; it certainly wasn’t the technical side — the math and all that. I believe there’s a shared skill set in being able to see context in a place. In my landscape architecture, I’m trying to communicate the character of a place that I’m designing. With my watercolors, I’m interpreting an existing landscape in a fine art context. Both relate to conveying a sense of place. Read the rest of Kelly’s interview with Tim in American Watercolor.  Tim Oliver, “Evening Shift North of Midland” (watercolor, 20 x 10 in.) |