“Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire.”

― Gustav Mahler

Visual art has a long history (to say the least) of practice, tradition, and training. And yet, art remains forever fresh and new for each new pilgrim to her shrine.

“Painting is easy when you don’t know how but very difficult when you do.” So said Edgar Degas, and what he meant by it only becomes clear after you have indeed been painting long enough to “know how.” The more you learn about it the clearer it becomes that painting has more to do with the challenge of personal growth than whether to use cadmium red light or cadmium red deep for a given rose petal.

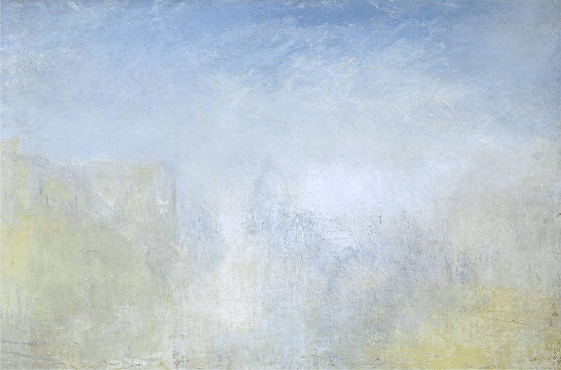

Of course you must learn the basics of composition, drawing, edges, color, and all the fascinating principles and techniques passed from master to student for hundreds of years. Design is HUGE in painting. Yet, in throwing ourselves into all these new concepts, we tend to neglect expression, the very thing that drives creativity in the first place. For the creative artist, tradition is a tool, not an end in itself. Think about how many so-called accepted rules Turner breaks in his painting of Venice below.

J.M.W. Turner, Venice with the Salute, c.1840-5 Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

After all, every standard academic technique was once an intuitive improvisation: An artist’s vision once demanded an expression with enough force that, out of desperation and intuition, they came up with a move that answered the sheer need to convey something important to the viewer, and a new technique was born.

Still, somehow we’re supposed to find our authentic voice AND learn the secrets of conjuring three-dimensional forms onto a two-dimensional surface – the stages of building a painting through design and draftsmanship, which tools to use and how, etc. etc. It’s a lot all at once!

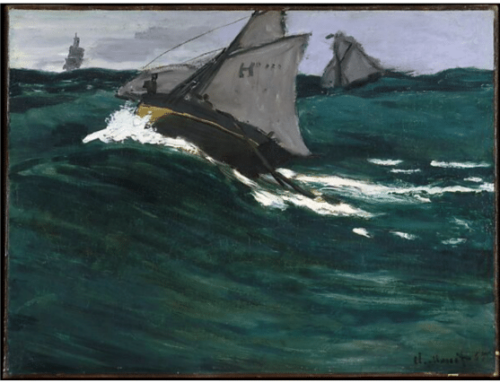

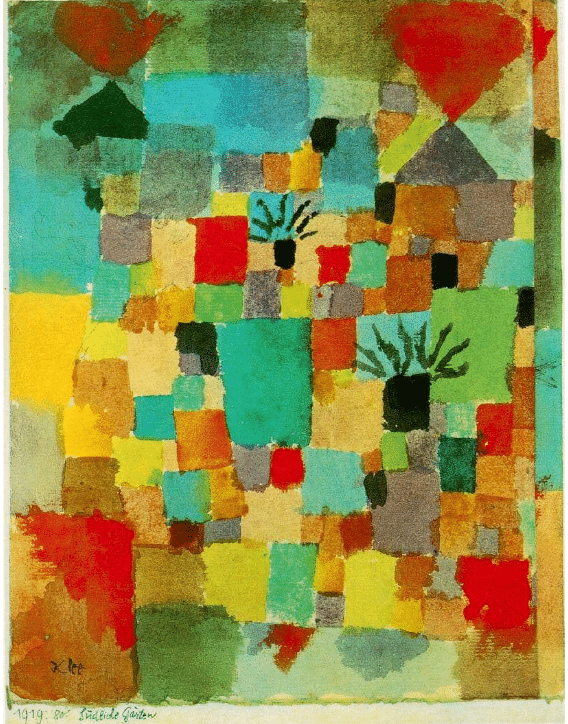

Paul Klee, Southern (Tunisian) gardens, oil, 1919

The real problem here is not the inability to create something of value – it’s our inability to see what’s of value in what we create. You have to see past technical shortcoming to how much of yourself you got into it and how you can carry that into your next canvas.

Because, and you already know this on some level if only you’d let yourself see and believe it, in each “hot mess” you make, there’s a little of yourself in there. There’s something unlearned, uncontrived, honest, and raw, something that corresponds to how you really feel and who you really are in the world. See that. Honor it.

You don’t have to show those paintings to anyone, but make them, keep them, own them for what they are and what they could be. The way to see them is to drop your preconceptions of what a painting is “supposed to look like,” just for a minute. Your so-called failures are the flagstones that will lead you to yourself.

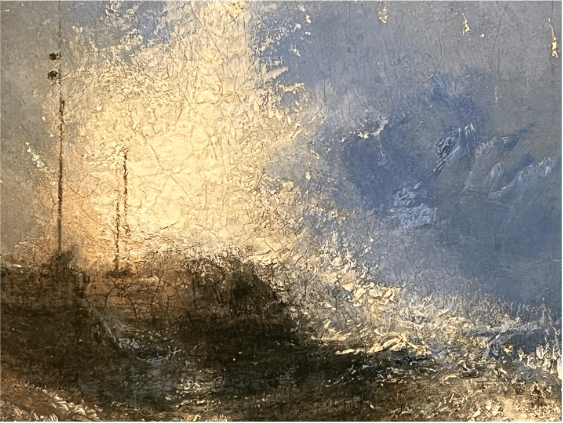

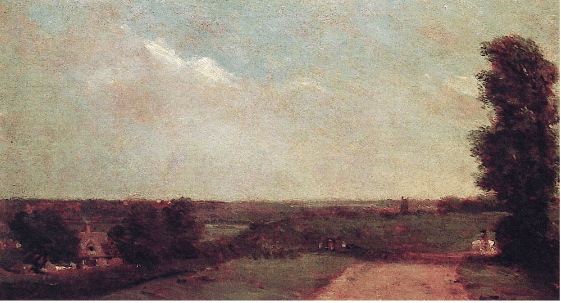

John Constable, View Towards Dedham, oil, 1808

Eventually, when you can allow your emotion to lead but not dominate, you will begin to combine academic technique and personal expression in the free interpretation of what you see and know.

Here are three ideas for stretching yourself as you reach beyond your boundaries:

- Find out what artists do. Seek out an historical artist whose work you respond to immensely and learn everything you can about them as a person. The only requirement is that they be dead. Do some deep-dive art history searches. Find the originators of what everyone is copying: find yourself a Sargent, a Turner, a Klee, a Raphael, Constable or Latour. Don’t settle for free YouTube documentaries; splurge on real art books and read the words in them. Find out what the critics, then and now, as well as what the artist had to say about the work. Seriously, go see the work in person whenever you can. Don’t study them to learn how to use oil paint, watercolor, or pastels; the most important lesson the masters can teach you isn’t about technique – it’s about what inspired them to make the work they did.

- Look at different kinds of art. We tend to gravitate to a particular genre of art and the artists who make it, but there are many art worlds. Stumble onto a few of them now and again. Follow some unfamiliar links online, read about art you aren’t even initially interested in, discover new galleries and seriously consider the merit of the work they show. Always be open to expanding your definition of art.

- Figure out what you have to say. Knowing yourself is a huge advantage as an artist. Ask yourself what you like and why you like it. Why this one, not that one? When it “speaks to you,” what does it “say”? What do you like about the work you admire – not just in terms of technique, but in terms of what’s behind it, what the artist put into it, what the work conveys about life!

Painting is just a fun thing to do sometimes. Yet, as you keep doing it you begin to appreciate the variety and range of amazing work out there, present and past. You also learn more about why people paint and the many was art enriches life, and you’ll want to be part of that more than ever. And you can. As Walt Whitman wrote, “the passionate play goes on – and you can contribute a verse.”

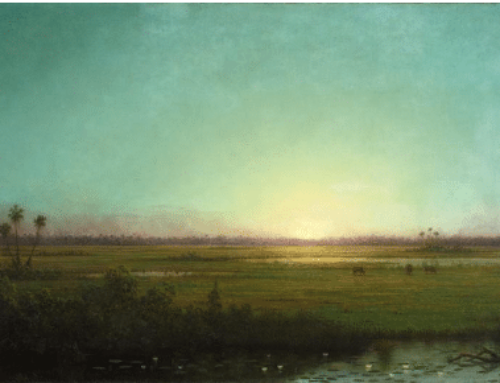

William A. Schneider, Sunset Over Queens, oil, copper panel, 16” x 20”

Design is probably the most important and most easily assimilated aspect of traditional technique. For a thorough overview, you might want to consider an instructional DVD such as William A. Schneider: Design Secrets of Masters – Key to a Successful Painting