You can learn a lot from looking closely at other peoples’ paintings of rocks, and there’s no better source than the Hudson River School painters. One of the best sources for study must be William Trost Richards, if only because he brought a mad geologist’s attention to factual topography to bear on the prevailing Romanticism of the day.

Painting rocks purely from observation somehow results in what looks like piles of gray sacks of potatoes (at least in my experience!). Knowing that’s the danger helps, because then you can compensate by purposely eliminating too many rounded forms and replacing them with sharper angles and harder edges. (That way at least they’ll look more like cardboard boxes than bags of vegetables!)

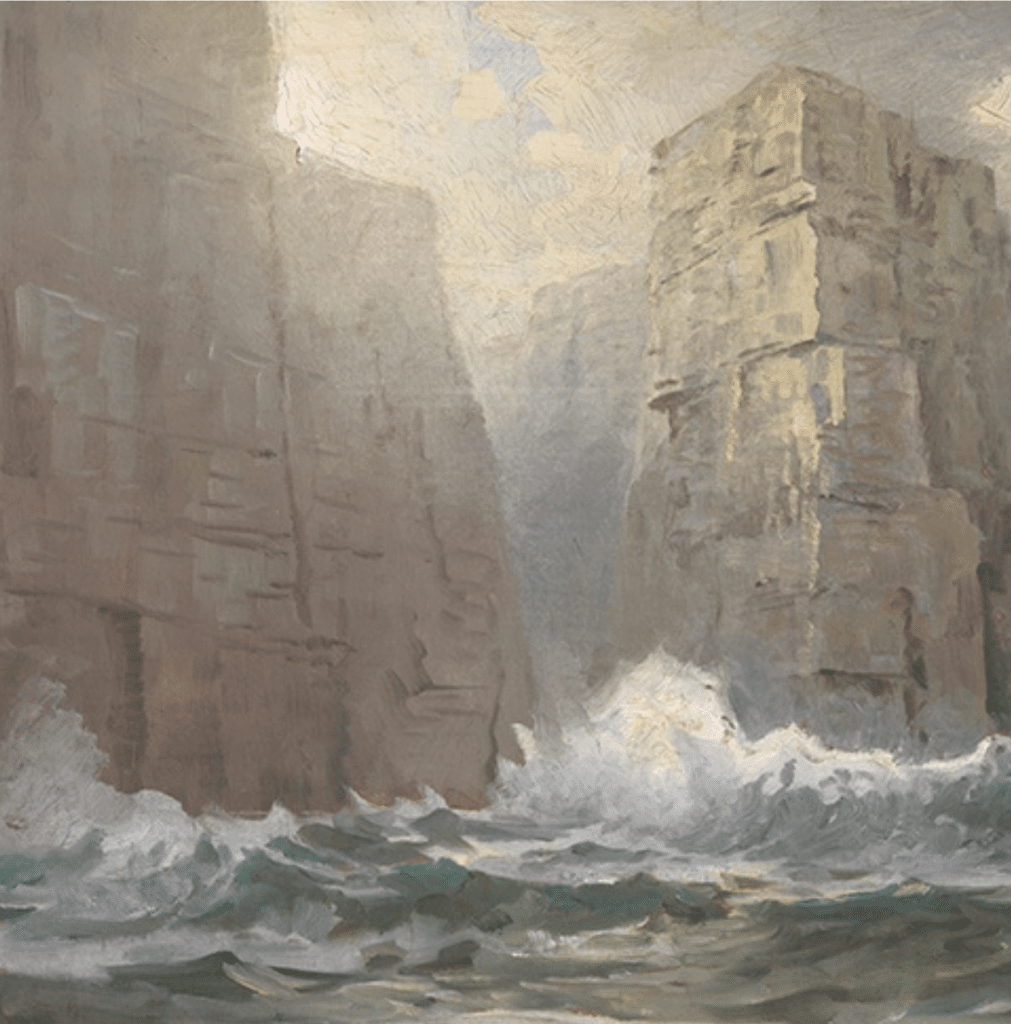

William Trost Richards, Untitled Seascape in Oil, Chrysler Museum

Nineteenth-century American landscapist William Trost Richards parted ways from his Hudson River School peers in two respects – one, he specialized in rocky coasts and large-scale seascapes instead of mountains and valleys, and two, he took a doggedly realistic approach to his subjects. His big seascapes are as full of feeling for the vastness and divinity of nature as any Hudson River landscape, yet his approach combines factual renderings, done with an extraordinary topographical precision and strong design, with the group’s hallmark scale, atmospheric breadth, and a sense of light verging on the spiritual.

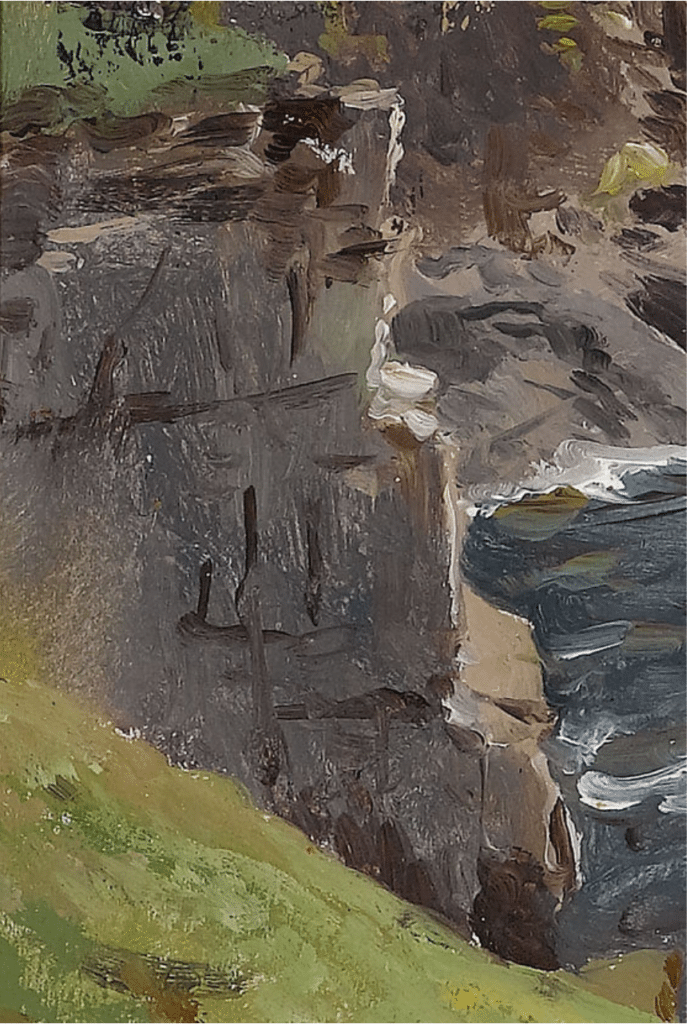

There is a great high-res image of Richards’ “A Rocky Coast” (above) on the website of the Metropolitan Museum. You can click the image above, click on it again to enlarge it, and explore every intricate line with your computer. Amazingly, this is a watercolor – but no matter. Draftsmanship (drawing) is the most important consideration when painting rocks, no matter the medium. Select a small section or two of this painting that you can copy onto a sheet of watercolor paper or an 6×8 or 8×10 canvas. Even if you just do a sketch in pen or pencil, you’ll learn tons.

Detail of “A Rocky Coast” by William Trost Richards

When painting his rocks, Richards probably roughed in the underlying area as a mid-tone, drawing a large-bristle brush across the canvas in the direction of the his rocks’ angles and then adding details (both darker shadows and brighter highlights) with a smaller brush, as was the method of his idol, Frederick Church.

You can see this method at work most clearly in the backlit cliff with its diffuse light on the lefthand side of the detail below.

Detail of a different WT Richards seascape showing the broad, directional, up and down strokes he laid down first and the detail lines he did after with a smaller brush (a palette knife will work well too)

Below I have created a simplified value study from a selected crop of “A Rocky Coast” (above) using my photo application’s basic editing features: you just remove the color (desaturate), dial up the contrast and punch up the exposure. (Color can be distracting and confusing when values are very close; removing the color and turning up the contrast makes it easier to see the most important lines, lights, and shadows. Simplify it even further when you paint the study.)

As you can see in the enlargements, we can break each rock down only three or four major planes joined at modified 90 degree-angles with flat (NOT rounded!) surfaces. It’s the subtle variations in the angles and the values, the fractures, chips and cracks, that clinch it. A close look at WT Richards’ approach shows he painted a flat mass first and then carved out the angles and details with a smaller brush.

Want to paint better rocks? Well, if step-by-step tutorials are what you need to create your best rocks yet, check out these two videos, Painting Rocks and Sunlight with Matt Ryder and Albert Handell’s Painting Water and Rocks in Oil.

In the Basket!

Lana Privitera wins First Place Overall in Monthly Salon

Lana Privitera, Looking for a Way Out, watercolor, 29″ x 21″

Lana Privatera’s watercolor, Looking for a Way Out, has been awarded First Place overall in the April PleinAir Salon. Catherine Saks of Saks Gallery was the judge. Additional winners and coverage to follow – stay tuned!

Enter your best work today in the PleinAir Salon, which rewards artists with over $33,000 in cash prizes and exposure of their work, with the winning painting featured on the cover of PleinAir magazine. The next deadline is soon, so visit PleinAirSalon.com now to learn more!