Abstract landscape painter Brian Rutenberg names as one of his favorite strategies what French painter Pierre Bonnard called the “void in the middle.” Though as a compositional approach it seems counter-intuitive not to center a painting on the main subject, it’s a device any landscape or figure painter should have in their toolbox. Let’s dive in.

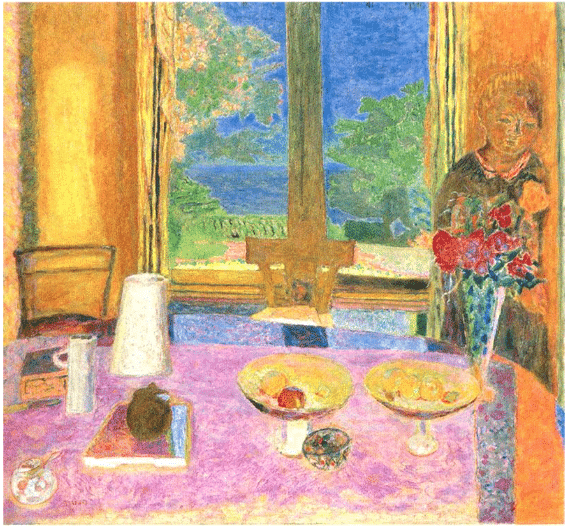

Bonnard painted many marvelously colorful and complex interiors, kitchens, bedrooms and drawing-rooms, in which he loaded up the sides of his paintings with subject matter, details, and thicker paint while leaving the middle relatively open. Sometimes he’d add a slight curvature to the space at the outer edges as well; the effect both mimics peripheral vision and draws the viewer into the painting and keeps the eye moving within it, going around the periphery and bouncing in and out of the center.

Pierre Bonnard, “Dining Room on the Garden,” 1934-1935, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Manhattan, New York City, USA, North America

It allows for a packed and otherwise potentially crowded surface to have variety and a little more air. Rutenberg often lays the paint down more thickly at the edges and more thinly and “vaporously” toward the middle, “to suggest humidity that sort of capitulation one experiences when it’s 108 degrees and you’re standing this deep in pluff mud in South Carolina being bitten by mosquitoes.” (Pluff mud is a thick, clay-like, dark brown mud that is made up of decaying matter, including marsh grass, fish, and animals. The mud is unique to South Carolina’s salt marshes.)

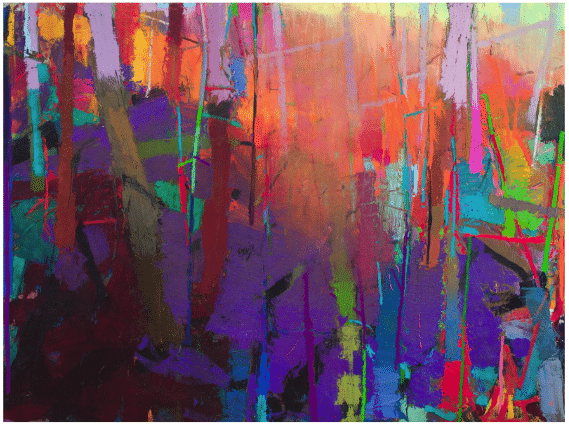

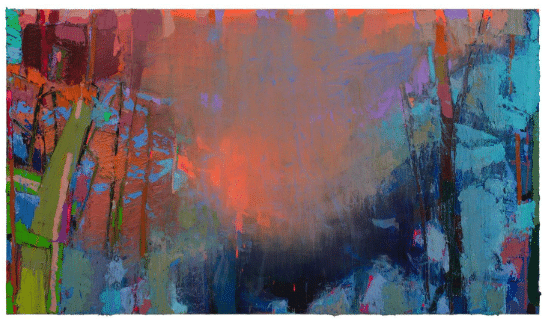

In his painting titled “Banner of the Coast (Silver Sides),” (below), Rutenberg uses the “void in the middle” design strategy to advantage. The sides of the painting teem with compacted shapes of jagged-edged color (much of it cool). As we move toward the center, the edges get lost and (Rutenberg is one of the best “youtube artists” for knowledge, advice, and inspiration; for years, Shapes dissolve into an increasingly atmospheric glow. Our gaze goes inevitably to the center of the composition, where everything seems to converge.

Brian Rutenberg, “Banner of the Coast (Silver Sides),” Oil on linen, 40×70 in.

The “void in the middle” design needn’t be confined to abstract landscapes. The circular composition, where the eye moves around the edges of the painting in a subtly designed circuit, might count as a distant cousin.

As in the painting below by Daniel Keys, there’s neither a void nor an atmospheric field suggesting distance. However there is a relatively calm and center in the magenta flowers there. It anchors the surrounding objects (like an axle) and offers space for the eye to keep coming back to as our vision travels from one object to another (vase to teacup to pitcher to vase to teacup, etc.)

Daniel Keys, “Spring Azaleas,” oil, 20×20 in. (Daniel Keys has a number of fascinating still life “how to” videos you can check into here.

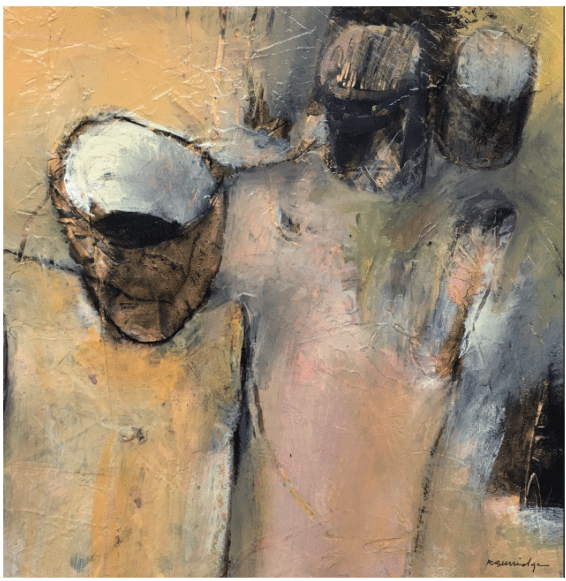

Often, it happens intuitively when an artist wants to arrange a group of things (clay bowls, for example, as in the abstract still life by Robert Burridge, below) without placing them all together or right next to each other. It allows for an unusually “open” design.

Robert Burridge, “Clay Bowls,” acrylic on paper mounted on board, 18 x 18 in.

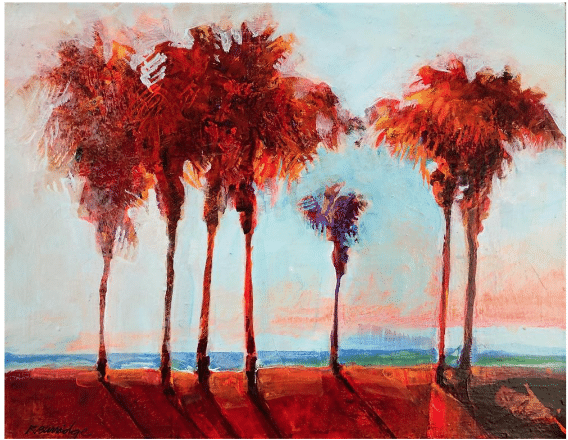

If you are interested in exploring a more abstract approach to your own painting, including landscape painting, maybe check out Robert Burridge’s video Painting Abstract Landscapes and Trees.

Robert Burridge, “After the Storm,” acrylic, 14×18 in.