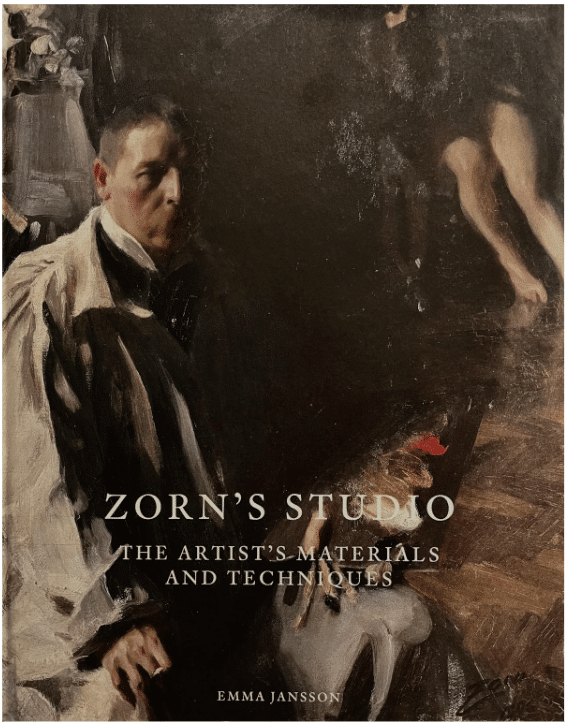

In a fascinating, well-written, gorgeously designed and photographed new book, Emma Jansson meticulously documents what every Zorn admirer has always wanted to know: how did this virtuoso of oil painting seemingly do the impossible again and again?

Anders Zorn (1860-1920) is regarded as one of the outstanding post-Impressionist Salon artists, classed among the Gilded Age portrait and genre masters such as Sargent, Sorolla, and the Italian Giovanni Boldini – inheritors of the Peintres de la Vie Moderne (painters of modern life) tradition, as Baudelaire had written.

It really is like being given free reign insid the artist’s studio, with all the delicious privileges and insights that imnplies. Through the pages of Zorn’s Studio, we follow Zorn’s every move, from his earliest techniques of applying paint through all the major shifts in his studio practice as his career developed. And Jansson takes us, literally, below the surface of the paintings, not only exploring the revelations of 21st century chemical analysis but also teasing our what they say about Zorn’s creative mind.

“There exists a popular perception that the artist favored a restricted palette consisting of only four colors – lead white, yellow ochre, vermillion, and ivory black,” write Jansson, “sometimes referred to as the Zorn palette.” Zorn did recommend a restricted palette to his students, and in his most famous self-portrait (visible in the above image of the book’s cover), his palette is deliberately displayed using only four dabs of paint. However, Zorn may have done this in a deliberate tip-of-the-hat to the Old Masters, notably Rembrandt, Velasquez, and Frans Hals, who had few other pigment choices and with whom Zorn wished to identify himself.

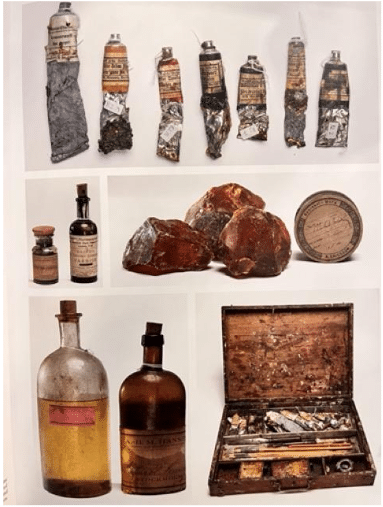

While Zorn certainly did generally use a limited mixing palette, “more recent analyses of his materials have shown that his palette also included a handful of modern synthetic pigments,” Janssen writes. Notable among these are viridian, cadmium yellow, and cobalt blue, without which Zorn would have been unable to mix his various combinations of purple and green, the latter of which dominate many of his landscapes. The bottom line:

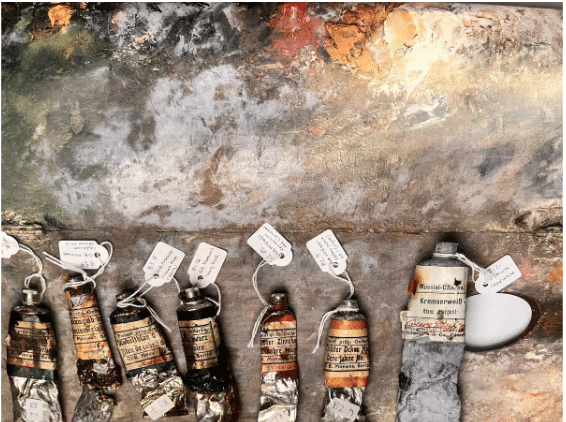

“Based on the technical examination of Zorn’s paintings using X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy and paint cross-section sampling, together with an assessment of his remnant palettes, tube paints and purchase orders, these additional colors have been identified as zinc white, Paolo Veronese green, chrome green, viridian, Emerald green, Naples yellow, cadmium yellow, burnt Sienna, madder lake, cobalt blue and ultramarine blue.” (That’s – count ‘em – FOUR greens, two blues and two yellows including Cadmium! a second red, and an earth, all more than likely to be found on any modern painter’s palette.)

The book is organized in two sections – the first consists of Zorn’s “Materials and Techniques” and the second is a catalogue of “Case Studies.” The “materials” section examines Zorn’s precise way of approaching the foundations of painting, revealing surprises at every turn, including:

- Canvases & Grounds (he mostly didn’t stretch his own)

- Palette (contrary to rumors, he used various blues and greens and cadmium yellow)

- Preparatory Works (contrary to rumors, he sketched and did studies first)

- Painting Techniques (contrary to rumors, he finished and often reworked his paintings in the studio)

- And Varnishes & Coatings (he often used thinned layers as opposed to the bolder and thicker paint applied by the alla prima Sargents of his time, to which he was being compared)

The rest of the book (more than half) is devoted to fascinating studies of individual paintings informed by meticulous scientific analysis. Here is where we learn, among other things, how modern infrared and x-radiograph analysis of key paintings discloses Zorn was not the spontaneous, premier coup painter he wanted people to think he was. Zorn worked up his finished paintings in the studio, only adding trademark rapidly applied brushwork as a final, finishing touch.

Don’t get the wrong impression – this book is by no means a “tear down” of Zorn’s legendary talent. Rather it’s the opposite- a celebration of his unique creative sensibilities, and at times downright transcendental technique. Separating the myth from the reality gets us closer to Zorn the man as well as the artist. This treatment does a tremendous service for today’s students of art and painting.

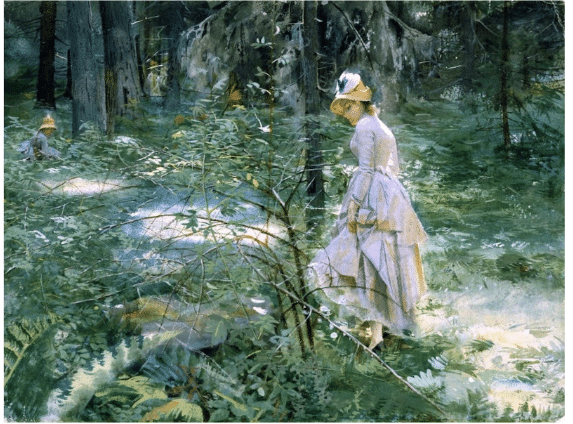

Anders Zorn, The Thorn Bush, oil

Would-be artists only hurt themselves when they remain frozen in hopeless awe before “magicians” like Zorn, Sargent, or Sorolla. These guys were human beings just like us; they had to learn by doing just like us and sometimes felt and acted as petty, as deceptive, and vulnerable as we do, inside and outside of their paintings.

Getting inside the heads of your heroes – understanding how and why they did as they did, seeing what was in their minds’ eyes as well as what was on their palette, what they were trying to do and what they wanted people to think – is one of the most important things you can do on your own creative journey.

Bottom-bottom line: this book would make an excellent gift for the artist in your life (including, of course, yourself).

If you’d like to explore the style Zorn shared with Sorolla and Sargent, have a look into Thomas Jefferson Kitts’ combo set of “Master Artists” teaching videos: Sorolla, Painting the Color of Light and Sargent, Techniques of a Master.

Final Weeks of Sorolla Show in Texas

Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, “Beach of Biarritz (Playa de Biarritz)” (1906), oil on wood panel, 8 7/8 x 7 1/8 inches (photo by Joerg Lohse)

“Everywhere the air was full of miracle,” wrote the American philanthropist Archer M. Huntington about Spanish painter Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida’s first major exhibition in the United States in 1909. “Nothing like it had ever happened in New York,” Huntington continued, “Ohs and Ahs stained the tile floors. Automobiles blocked the street.”

Today Sorolla is an artist’s artist, meaning he isn’t a “household name” like Sargent, the American equivalent to which he is compared, but anyone who paints in oils long enough runs into him and finds themselves in awe of his work.

Now entering its final weeks, an exhibition at the Meadows Museum in Dallas, Spanish Light: Sorolla in American Collections is showing 26 rarely exhibited paintings by the artist from private collections in the US. Curated by Blanca Pons-Sorolla, the artist’s great-granddaughter and a notable scholar of his work, the show is a rare chance to behold the work first hand of one of the greatest, if lesser known, painters of the previous century.

For a deep dive into Sorolla’s technique, have a look at the Master Artists video, Sorolla, Painting the Color of Light by Thomas Jefferson Kitts.