What do people mean by the “expressive landscape”?

Usually, it’s landscape painting that prioritizes the qualities of the paint over paint’s ability to represent what the eye sees. It can also refer to landscape painting that in some way radically simplifies, selectively chooses, enhances, or reconfigures certain aspects of the observed world to create something new that “tells a story” or emotes feeling.

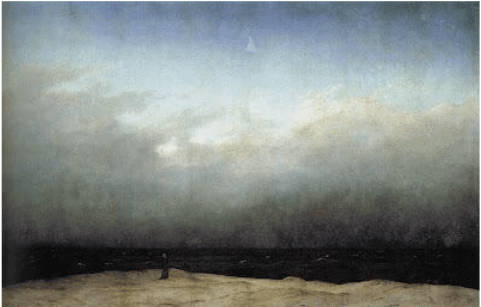

Some art historians consider Casper David Friedrich’s stark 1810 painting, The Monk by the Sea a kind of precursor to abstraction. This work struck people of the time as really extraordinary. It sounded a note in painting more desolate and existential than had ever been heard.

“No situation in the world could be more sad and eerie than this—as the only spark of life in the wide realm of death, a lonely center in a lonely circle…,” wrote an early admirer of the painting. “Since in its monotony and boundlessness it has no foreground except the frame, when viewing it, it is as if one’s eyelids had been cut away.” Yikes!

Friedrich in hindsight seems to have been a painter of the human search for an elusive spiritual homeland. He often included symbols and allegories in his work that evoke relationships between humanity, God, religion, and mysticism.

Here, the tiny figure of the monk can function simultaneously as a symbol of the spiritual inner life, a self-portrait of the artist, and a stand-in for the viewer. He/we are dwarfed by three different kinds of voids, land, sea, and sky: the bare and pallid grassless foreground, the iron-black bar of the sea that shuts down the middle, and the amorphous expanse of vastness-stepping-off-into-eternity that is the sky that occupies the majority of the painting.

Without a repoussoir—a framing device that leads the viewer’s gaze into the image – the emptiness of the foreground disrupts the viewer’s relationship to traditional picture space. One cannot mentally “penetrate” the image: Friedrich has created an unbridgeable gap between the figure and the viewer. The monk is cut off from us spatially and existentially, and there are no traditional landscape elements to soften the effect. James MacNeil Whistler took this even further in his Harmony in Blue and Silver: Trouville, 1865 (below).

James MacNeil Whistler, Harmony in Blue and Silver: Trouville, 1865

In June 1809, the wife of one of Friedrich’s visiting artist friends wrote in a letter how shriveling she felt the loneliness of the setting to be. She deplored the lack of consolation that a little more content – some sort of movement or narrative – might have brought to the painting’s “unending space of air.”

Critics agree with her description but not necessarily her judgments about it. Art historians see The Monk By the Sea as perhaps the first ‘abstract’ painting in a sense, because of its radical “color field” style of composition and overall flattened picture plane.

Friedrich wasn’t trying to be “abstract” or innovative so much as he was being expressive of a feeling about life. He chucked the rules and put all of his highly trained skill and technique behind the expression of something he personally felt deeply. It was something that had never been expressed like this because it probably hadn’t really been felt this way before, at least on a cultural scale – that is, the sense that a modern world was coming with the power to shake the old classical, Enlightenment world view of the previous century to its core.

What does Friedrich gain by purposely leaving out the conventional devices that create depth? He wants the viewer to feel confronted by the question of mankind coming up against a vast and quite possibly “empty” universe, a world, as the existentialist philosophers 200 years later would describe it, from which spirituality, contentment, and higher ideals were seemingly draining away.

Gustav Courbet’s answer to Friedrich (or was it Whistler?): The Beach at Palavas,1877

It’s been compared to many other more or less abstract paintings, in addition to the works by Whistler and Courbet above. Some see it pointing in the same direction as the work of a still often misunderstood artist of our own time, abstract expressionist Mark Rothko.

William Nicholson, Mending the Nets, c. 1910

Mark Rothko – Light Earth and Blue, 1954.

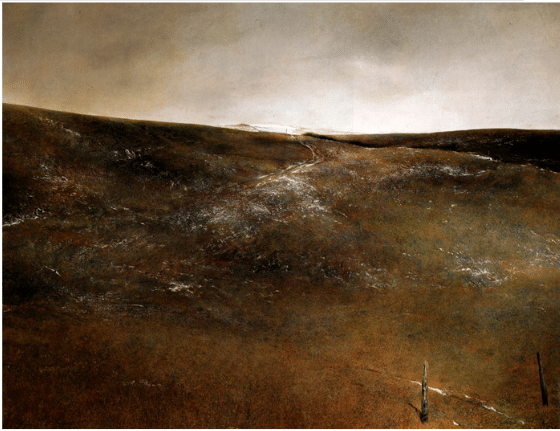

Because of the way Friedrich seems to have felt nature, you get the sense of vast spaces up against the relative smallness of humanity. One can read a certain kinship of feeling in Andrew Wyeth’s stark “Snow Flurries” (below) as well.

Andrew Wyeth, Snow Flurries

If you are ready to explore expression in your landscape work, you might want to have a look into Jove Want’s video, Expressive Cityscapes.