I find it strange that people who make art hesitate to call themselves artists. I know lots of “people who paint” or “just mess around,” or worse, “used to be” artists but now just “paint because they enjoy it.” All these people are artists, and if you’re making art at all (especially if you’re enjoying it!), you are too.

Here’s what it comes down to:

“There really is no such thing as Art. There are only artists.” So begins the most famous and popular book on art ever published, “The Story of Art,” by E.H. Gombrich. In print since 1950, it remains one of the most readable and accessible introductions to the whole subject, from the earliest cave paintings to contemporary art, circa 1989. “Probably no other book in the world represents the priceless heritage of mankind so elegant and easily,” as one enthusiastic online reviewer summed it up.

I’ve owned several copies, but the one I have now is a wonderful pocket edition published by Phaidon. It’s thick but lightweight, thanks to the elegant “onion skin” paper it’s printed on. It has two satin ribbon bookmarks, one to keep your place in the text and one so you can follow along as you refer to the beautifully printed color illustrations that form the whole second half of the book. It’s a super well designed companion you can take anywhere.

I think people sometimes shrink from calling themselves artists because the word is so loaded with expectations and cultural baggage. I wonder sometimes, if part of the issue – besides a lack of confidence – is that society, and many artists too, have a distorted idea of the history of art and artists.

We tend to know the so-called Genius artists and their handful of universally revered masterpieces. What you learn from reading art history though, is that it’s a messy incremental process, even for the rockstars of art. Everybody is trying to do the same thing with basically the same tools, which is to do something meaningful and memorable that connects with others.

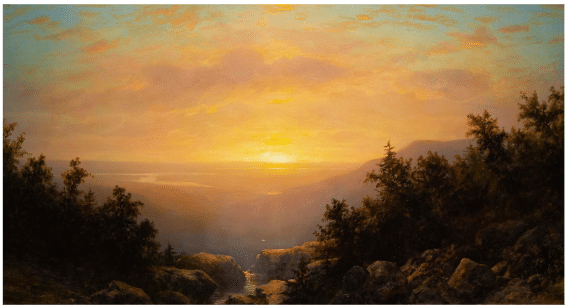

Erik Koeppel, “Sunrise Over the Hudson,” oil on canvas, 18.5 x 33.5 in.

That’s what artists do, and a lot of art by many artists, most of whom are not household names (amateurs included), does that in spades. Even if you’re just *trying* to do something real or good you’re part of the gang, and you get to call yourself an artist.

Erik Koeppel’s videos teach you the rich variety of techniques of the Hudson River School Masters in two volumes, Vol. 1 I and Vol. II

Artists who understand basic history get that it’s not a zero sum game or a “you have it or you don’t” proposition. It’s a process even for the greats, and no one feels like they ever know enough. Studying strong paintings is surely one of the best ways to learn how to apply the skills you acquire as you learn to paint. Why not study the greatest work ever made? For the first time in history, the entire history of art is freely accessible to all (via the web), but it’s not in any manageable order. For that, books like “The Story of Art” can help.

Contemporary academics have plenty of bones to pick with Gombrich, because it’s extremely out of fashion to talk about things like universal beauty, truth, and the human spirit. More’s the pity. If you take issue with humanism, you’ll find him the perfect pin cushion. There’s no denying that the book is “dated”; after all it was written almost 75 years ago and last revised in 1989.

But the heart of “The Story of Art” is in the right place and the author writes with as much clarity and appreciation of ancient pre-Columbian Peruvian, Inuit, Islamic, and Chinese art and architecture that he applies in the sections on classical Greek, Renaissance, or Impressionist painting. And if there were ever a time we needed more champions of what’s worthwhile in human endeavor, it’s now.

“Actually, I don’t think there are any wrong reasons for liking a statue or a picture,” he writes. What’s important, he says, is to approach all art free of prejudices, assumptions, and knee-jerk judgments. Gombrich wants to teach us how to “learn the language” used by artists whose work falls outside the realm of what we “like” simply because it’s what we already know and understand.

“Actually, I don’t think there are any wrong reasons for liking a statue or a picture,” he writes. What’s important, he says, is to approach all art free of prejudices, assumptions, and knee-jerk judgments. Gombrich wants to teach us how to “learn the language” used by artists whose work falls outside the realm of what we “like” simply because it’s what we already know and understand.

And from the artist’s point of view, knowing and understanding more about art, past and present, can significantly strengthen your grasp on the essentials of what you’re doing and why (and, arguably, help make you a better artist for it).

“One never finishes learning about art,” writes the author. “There are always new things to discover. Great works of art seem to look different every time one stands before them. They seem to be as inexhaustible and unpredictable as real human beings. It is an exciting world of its own with its own strange laws and its own adventures. Nobody should think he knows all about it, for nobody does.”

The Secret to making and understanding art? An open mind.

“Nothing, perhaps, is more important than this,” says our guide, “…that to enjoy these works we must have a fresh mind, one which is ready to catch every hint and to respond to every hidden harmony: a mind, most of all, not cluttered up with long high-sounding words and ready-made phrases…. To talk cleverly about art is not very difficult. To look at a picture with fresh eyes and to venture on a voyage of discovery into it, is far more difficult but also a much more rewarding task. There is no telling what one might bring home from such a journey.”

I hope to write a number of Inside Art articles in which I share some small gems from the vast treasures to be found in the works examined in “The Story of Art.”

Meanwhile, a great source for insight into contemporary fine art and its ties to the past is the Streamline publication Fine Art Connoisseur.