By John MacDonald

A glaze is traditionally defined as a thin, transparent layer of color applied over a dried under-painting in which its color, and the colors of any previous layers of glazing, are allowed to show through. The technique of glazing has existed for centuries, so its methods of application, the mediums and brushes used have evolved considerably.

Today, different artists advocate using different techniques and materials. Trying to summarize, much less describe in depth, each method of glazing, from the tradi- tional to the newest, is far beyond my expertise or desire. Here, I’ll just describe the two specific ways I work with glazes. They’re not the only ways to use glazes, but they give me the effects I want in paintings. There are countless other methods and materials for glazing. If you find the technique beneficial to your paintings, explore them all.

Transparent Glazes, Traditional Method

Transparent glazes are used primarily to create or change color. They can be applied to a small area of a painting or over an entire image to create an overall tone. Glazing with transpar- ent pigments can be used to change color temperature, darken value relationships, shift satura- tion/chroma, or mute specific colors (by adding a glaze of a complementary color).

The traditional method of using glazes begins with a grisaille – a monochromatic, opaque underpainting. Multiple layers of transparent glazes are then applied to create

color, each glaze comprising a single hue.

The colors in the finished painting are created by the optical mixing of all transparent layers rather than the physi- cal mixing of pigments into a single, opaque layer. The grisaille establishes the value structure, forms, and details in the painting while each succeeding layer of glaze provides color. Most of the painting process involves glazing, one layer upon another. This method requires patience, thorough technical knowledge, and a clearly defined plan. (None of which, I confess, are my strengths nor interests as a painter.)

When well done, it can result in as- tonishingly luminous color and a nearly photographic realism with a glasslike, perfectly flat surface.

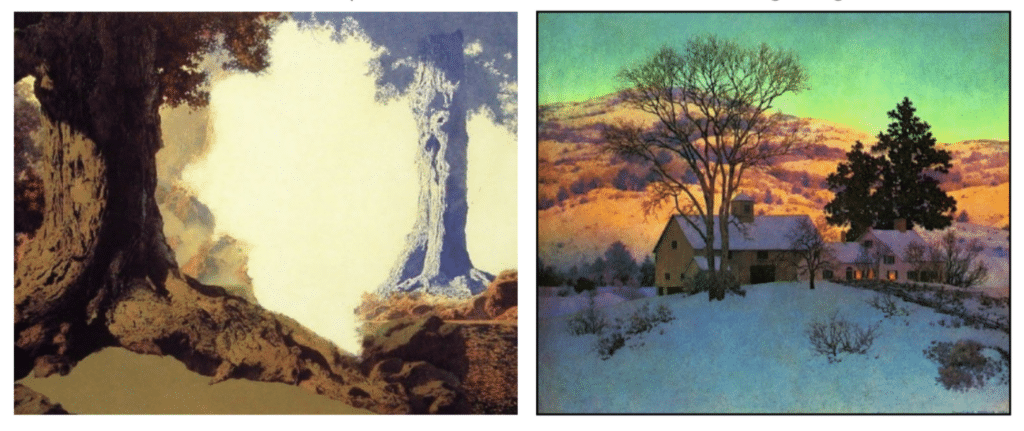

In the unfinished painting by Maxfield Parrish (above, left), it’s clear how methodical and controlled were his applications of glazes. On the right, a finished work of Parrish’s shows the beautiful color and luminosity that can result from skillful glazing.

Transparent Glazes Today

An alternative method of applying a transparent glaze is to use it to create a desired effect in the end stages as the painting. Most contemporary artists, myself included, use glazing in this fash- ion. It’s a secondary, not primary way of painting. Some paintings require it, some don’t.

In the nearly completed painting above (left), the snow line beneath the trees needed to be darker and more intensely blue. Applying an opaque mixture would have produce the correct value but using a transparent glaze of Prussian blue and a touch of Dioxazine Purple created a blue of the right value but with a higher intensity of saturation and transparency.

CONSIDERATIONS when using transparent glazes:

• A layer of transparent glaze will almost always darken the area to which it is applied. Adding a very small amount of white may be necessary to adjust values but be cautious when adding white. The more white, the less transparent the glaze.

• Because a color mixed optically by two or more transparent layers is always more satu- rated (higher in chroma) than the same color mixed physically as a single opaque layer, us- ing glazes is ideal for creating highly saturated color mixtures, especially in the lightest val- ues where the addition of white would make the resulting color chalky, or in the darkest darks. Glazing can be used to create dark shadows that glow with color.

• Using a transparent layer of glaze of a grayed, muted color, rarely works well.

• When painting highlights, transparent glazes applied over white are perfect for adding subtle color to snow, sunlight in the sky, etc., while preserving saturation.

• A transparent glaze can be applied to a roughly painted surface and then wiped or scraped off to accentuate the texture in the brush or knife work.

• Transparent glazes are perfect for creating gradients with subtle value shifts and or smooth changes in color.

In the subsequent parts of this essay to be published in future issues, John MacDonald covers opaque glazes as well as how to mix and apply the medium he uses for transparent and opaque glazing in his oil paintings.

John MacDonald teaches the essentials of his painting methods in several videos, one of which, Understanding Values, provides beginners a rock-solid foundation for one of the crucial aspects of painting no matter the style.

A Quick Guide to Transparency and Opacity

By Pat Fiorello

(patfiorello.com)

As artists, we think about our paints in terms of hues, color temperatures, values, and intensity. But there is another aspect of the physical characteristics of our paints that is important and that is the distinction of transparency vs opacity.

Understanding the different capabilities of transparent and opaque paints gives you a powerful addition to your painting tool kit.

One major visual difference between the two types of paints is how light comes back to your eye from the painting surface. With opaque paints, the light hits the surface of the paint and bounces back to your eye. Transparent paints operate more like a sheer veil of color. The light will hit the paint and since it’s transparent, will penetrate through to the ground (whether white watercolor paper or a white canvas) and will bounce back thru the transparent paint and back to your eye. In this way, it is like backlighting, which gives transparent paints their luminosity and glow.

In my own painting, luminosity and clean, bright color is important, so I generally start exclusively with a transparent wash/underpainting. This allows me to keep the color clean and avoid mud. I share this method in my workshops and go into greater depth on the topic in my instructional video, “Vibrant Flowers,” available through PaintTubeTV.

Opaques have the benefit of coverage with heavier body to create thick, impasto strokes. Transparents can provide contrasting thinner passages, and allow you to optically mix, since you can see one color through another.

For example, if you lay a transparent blue, like ultramarine blue, over a yellow, you will see green. The transparent blue will not totally cover what’s beneath it. Transparents are often very dark in mass tone. When two are mixed together, you can get some really dark darks. Yet when white is added to a transparent paint, it can act as high chroma opaque. Try adding a touch of white to transparent phthalo green, permanent rose, or Indian yellow.

How to Tell if a Paint is Transparent or Opaque

There are several ways to distinguish between the two types of paint.

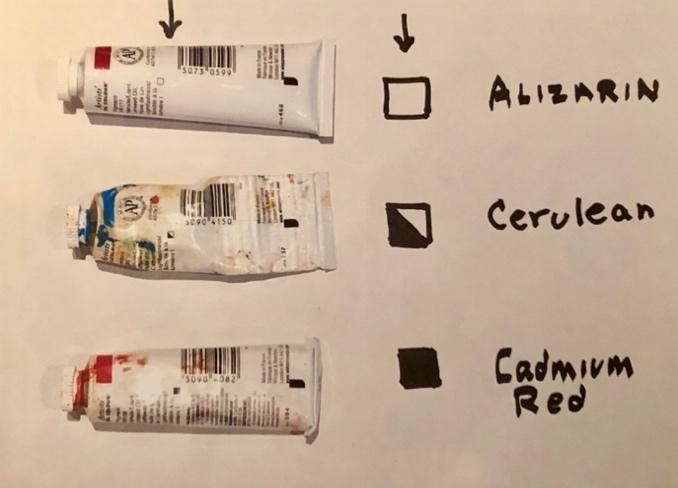

– First, often on the paint tube itself there will be a small box. If the box is empty, the paint in the tube is transparent. If the box is solid, then it’s opaque. If there is a diagonal line, that paint is semitransparent, somewhere in between. Unfortunately, not all brands carry this indicator on the package, but many of the major brands do, so take a look at your paint tubes. For those tubes that don’t have the box, they often note on the back label if the paint is opaque or transparent.

– If there is no indication on the package itself, look on the website for your paint brand.

– For some paints, like transparent red oxide and transparent oxide brown, it’s easy. Transparent is right in the name.

– A quick test you can do for yourself to determine which of your paints is transparent or opaque is to make a vertical line of black acrylic paint or ink. Let it dry. Then run a horizontal stripe of any color over the black line. You will see that opaque paints sit on top of the black line. They appear to advance in front of the line. Transparent paints seem to go behind the black line because they don’t have the same covering power as the opaques.

In my example below, I used cadmium yellow, yellow ochre, and Indian yellow for the yellows; cadmium red, alizarin, and permanent rose for the red family; and cerulean and ultramarine blue for the blues. I also included titanium white, transparent oxide red, and viridian.

You can clearly see for yourself that the cadmiums, yellow ochre, cerulean and white sit on top of the black line where the transparent colors, like Indian yellow, seem to pass behind it. With their excellent covering power, the opaques cover up the black line, but transparent colors cannot completely cover the line.

(Note this same exercise can be done with watercolors. Opacity is a function of the pigment, not the medium, so an opaque paint in oils is also opaque in watercolor.)

I encourage you to do some experimenting on your own with the paints you have, to better understand which are opaque and which are transparent and discover how each type offers particular benefits to your own painting process. The paint in our tubes not only varies in color but in covering power too.