Under the name of “Phoebus Apollo” (Phoebus is a Greek word that means “shining, radiant, bright”), the god Apollo daily drove the sun across the sky, manning a chariot drawn by four barely controllable horses.

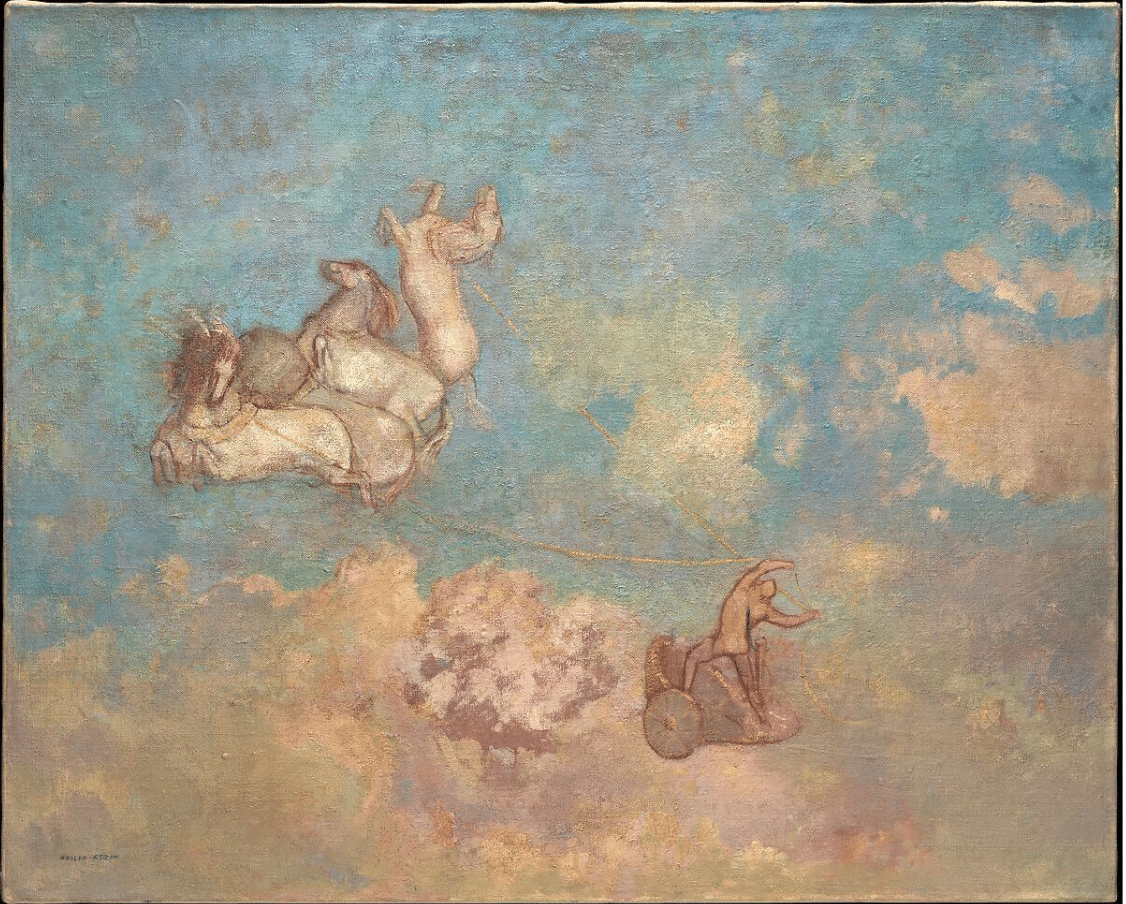

In Odilon Redon’s painting (above) the chariot may be driven by Apollo, god of light and poetry, or by Phaethon, Apollo’s half-mortal son, whose foolish attempt to steer the horses had serious consequences, as we’ll soon see. Redon made over 30 depictions of the motif in oil, pastel, and pencil. In this version, he omitted any indication of a ground plane, so that the horses and charioteer appear to race across a boundless sky.

Redon intentionally painted the horses and charioteer in a simplified style less concerned with realism in favor of the stranger symbolic representations we meet in dreams. It’s his color that floors us most though, even today. Contemporary painters can find a refreshing sense of possibility and daring in these harmonies of peach, gold, aqua, violet, grass-green, turquoise, tangerine, pink, and ultramarine. Redon’s colors are rich, varied, and radiant without ever seeming glaring – no mean feat, that. As you can guess from studying the colors, a big part of the secret is, of course, mixing – not using anything straight out of the tube, especially white.

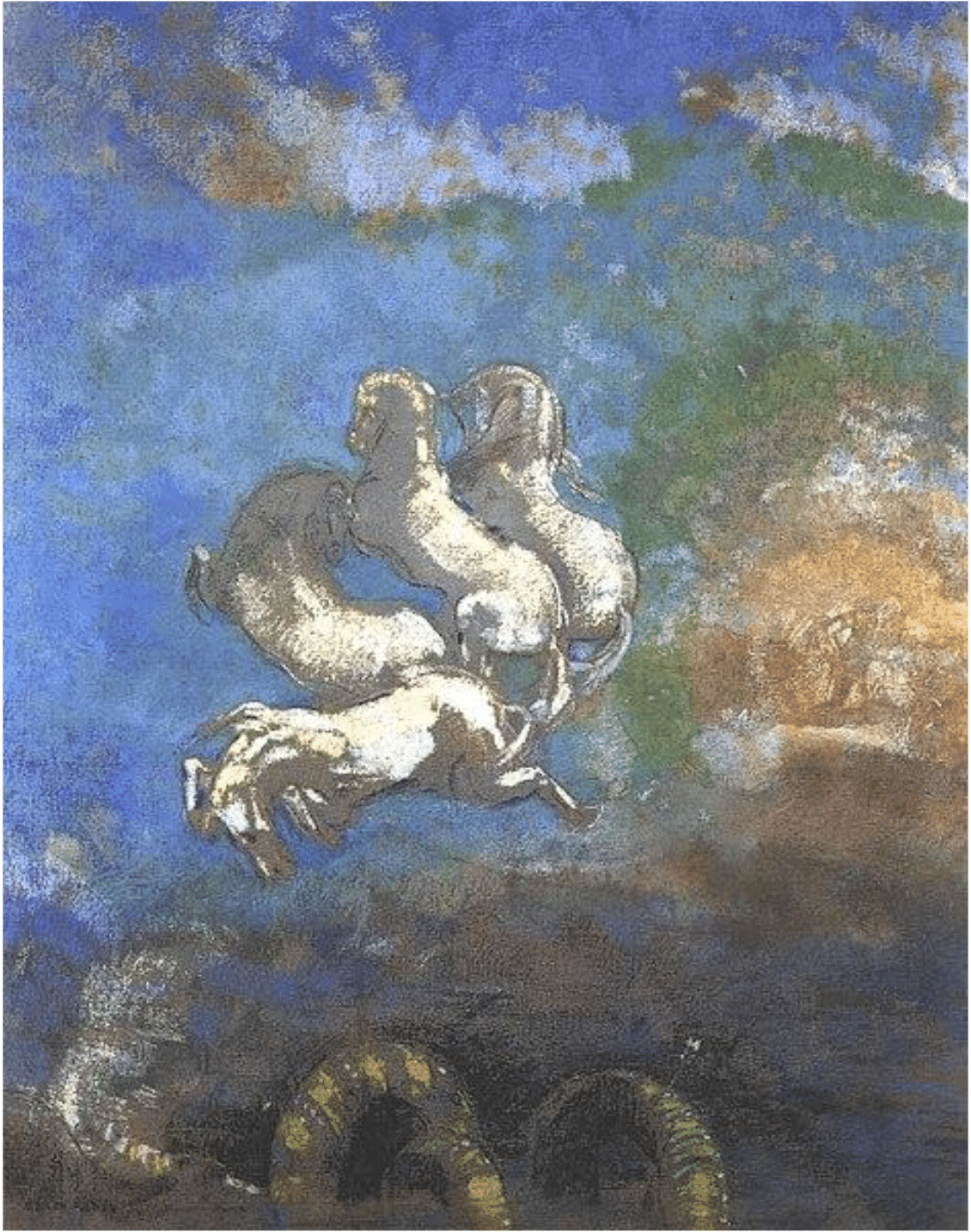

Redon takes a different approach to color when using pastels, as in the version below.

Odilon Redon, The Chariot of Apollo, pastel, unknown date.

The myth of Phaëthon, Phoebus’s son, has inspired paintings by some of Europe’s most renowned masters. In the story, which is found in Ovid’s collection of myths titled Metamorphoses, Phaëthon asks Apollo to give him a way to prove to his bullying friends that he’s really the son of a god. Apollo basically says, “Sure, kid, anything you want.” Phaëthon says, “Cool! Let me drive the chariot of the sun.” and Apollo, bound to his word (oath), has to let him. So Phaëthon jumps up, grabs the reigns, and immediately loses control, running the sun off its course. Ovid relates how the chariot gets too close to the earth and starts melting the polar regions, setting the world on fire, mountains first:

…. The highest altitudes

are caught in flames, and as their moistures dry

they crack in chasms. The grass is blighted; trees

are burnt up with their leaves; the ripe brown crops

give fuel for self-destruction—Oh what small

complaints! Great cities perish with their walls,

and peopled nations are consumed to dust—

the forests and the mountains are destroyed.

The earth’s rivers turn to vapor and that’s the final straw for Gaia, the Goddess of the Earth. She demands that Zeus intervene. The king of the Olympians hurls a thunderbolt, nailing Phaeton, and the chariot crashes to the ground in splinters, its horses scattered.

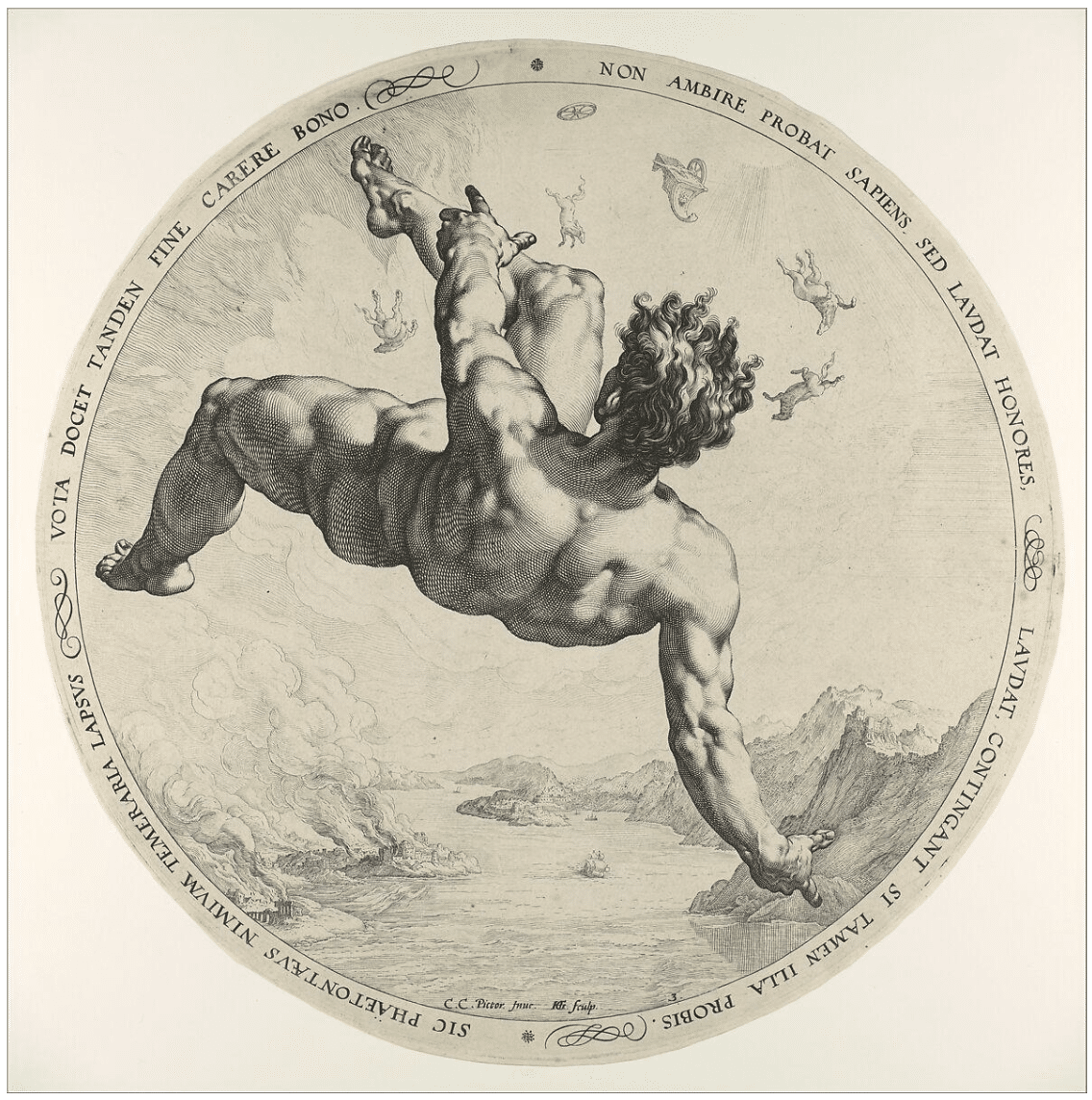

To my mind, the Phaeton myth is about that oh so winning combination of ignorance plus arrogance that pops up in politics and disastrous world events again and again throughout history. To the great artists of Europe, it was an opportunity to paint the human figure in a radical variety of poses and unusual angles in space.

Hendrick Goltzius, Phaeton, from “The Four Disgraces” series. (1588)

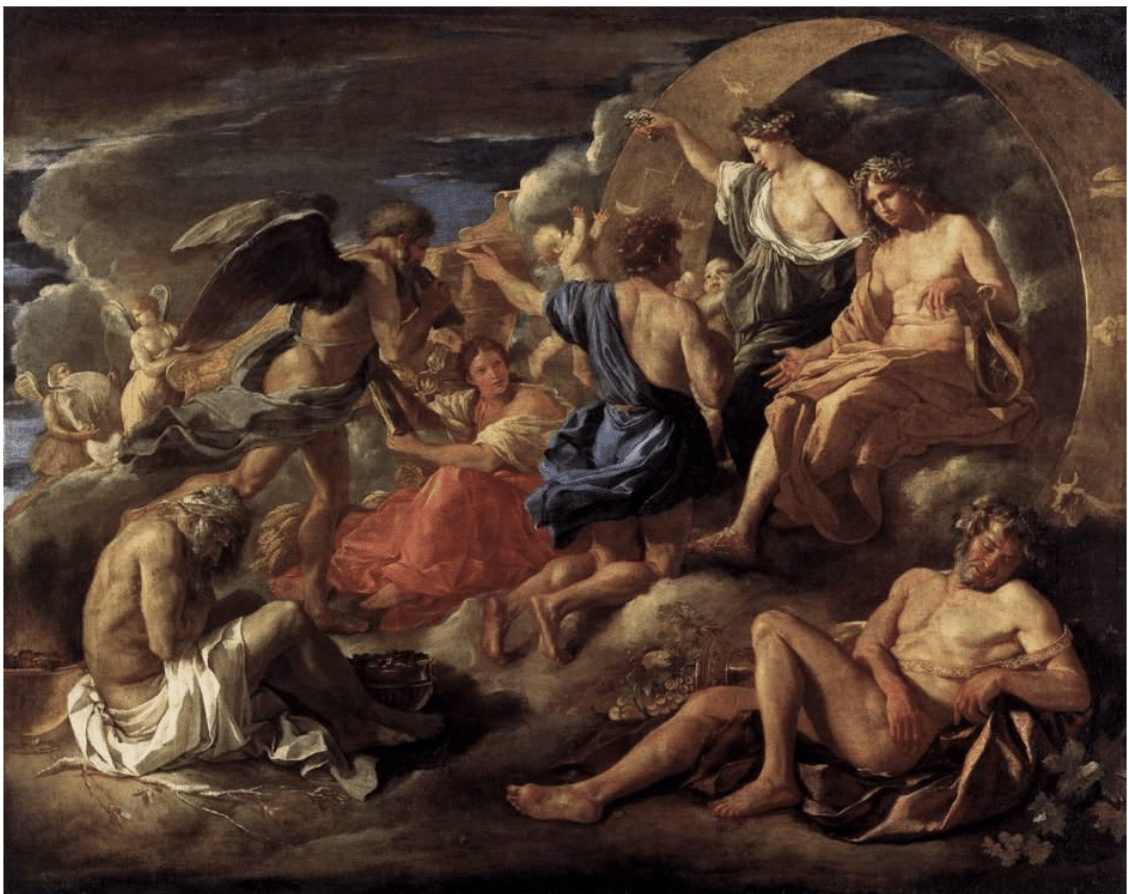

Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665), Helios and Phaeton with Saturn and the Four Seasons (c 1635), oil on canvas, 122 x 153 cm, Staatliche Museen, Berlin. Wikimedia Commons.

In Poussin’s Helios and Phaeton with Saturn and the Four Seasons (c 1635), Phaëthon (in the blue tunic) is on his knees in front of Helios, god of the sun (who would later be replaced in the myth by Apollo), pleading to be allowed to take charge of the chariot of the sun, just visible behind and to the left. That’s the ring of the Zodiac arcing over the figures, which is the track the sun’s chariot is supposed to follow.

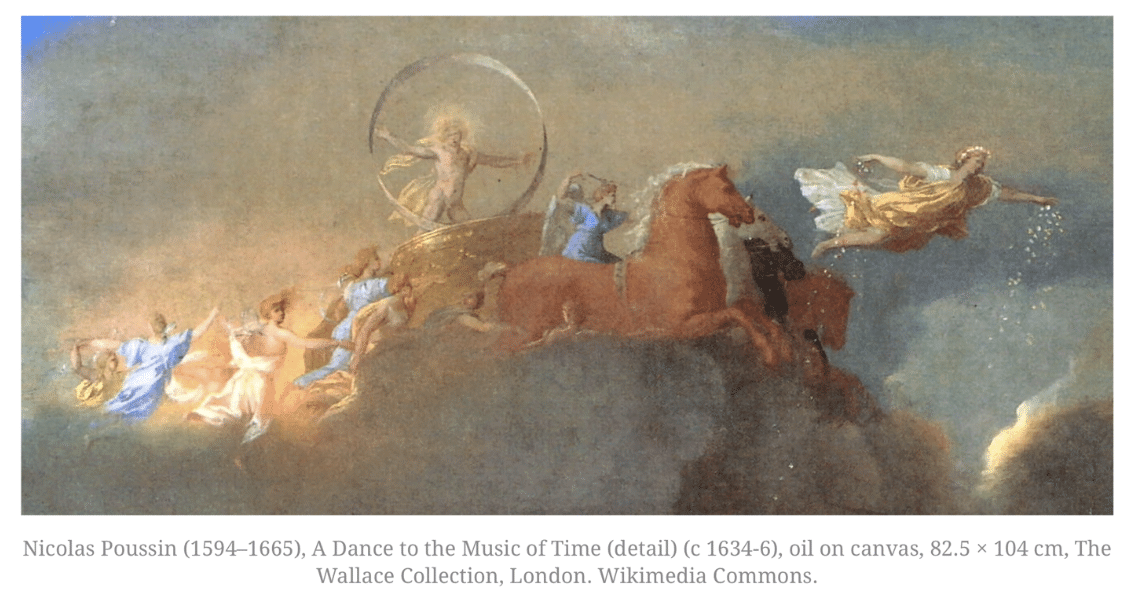

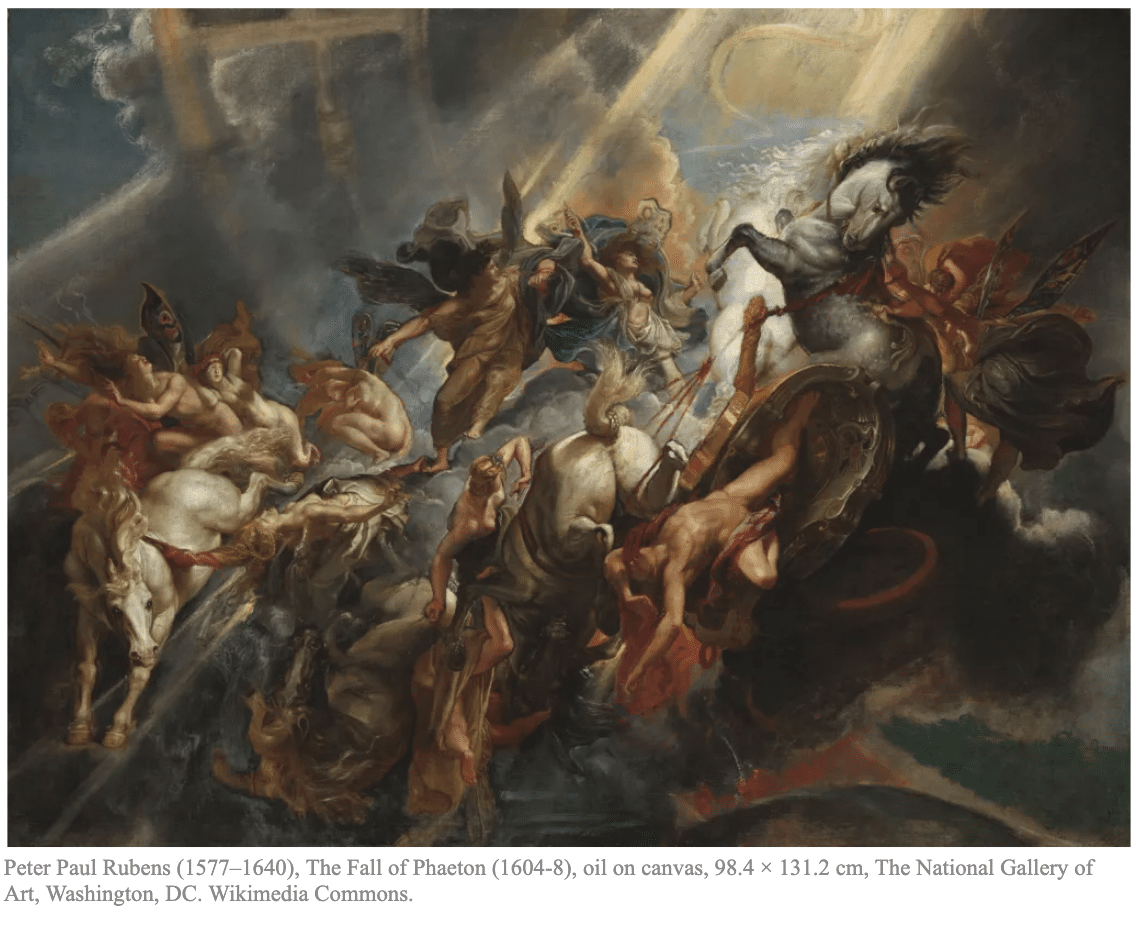

Rubens’ The Fall of Phaeton, above, embraces the chaos, peopling the scene with all kinds of supporting actors, including the Hours, some of whom wear butterfly wings, looking full of dread as everything goes south.

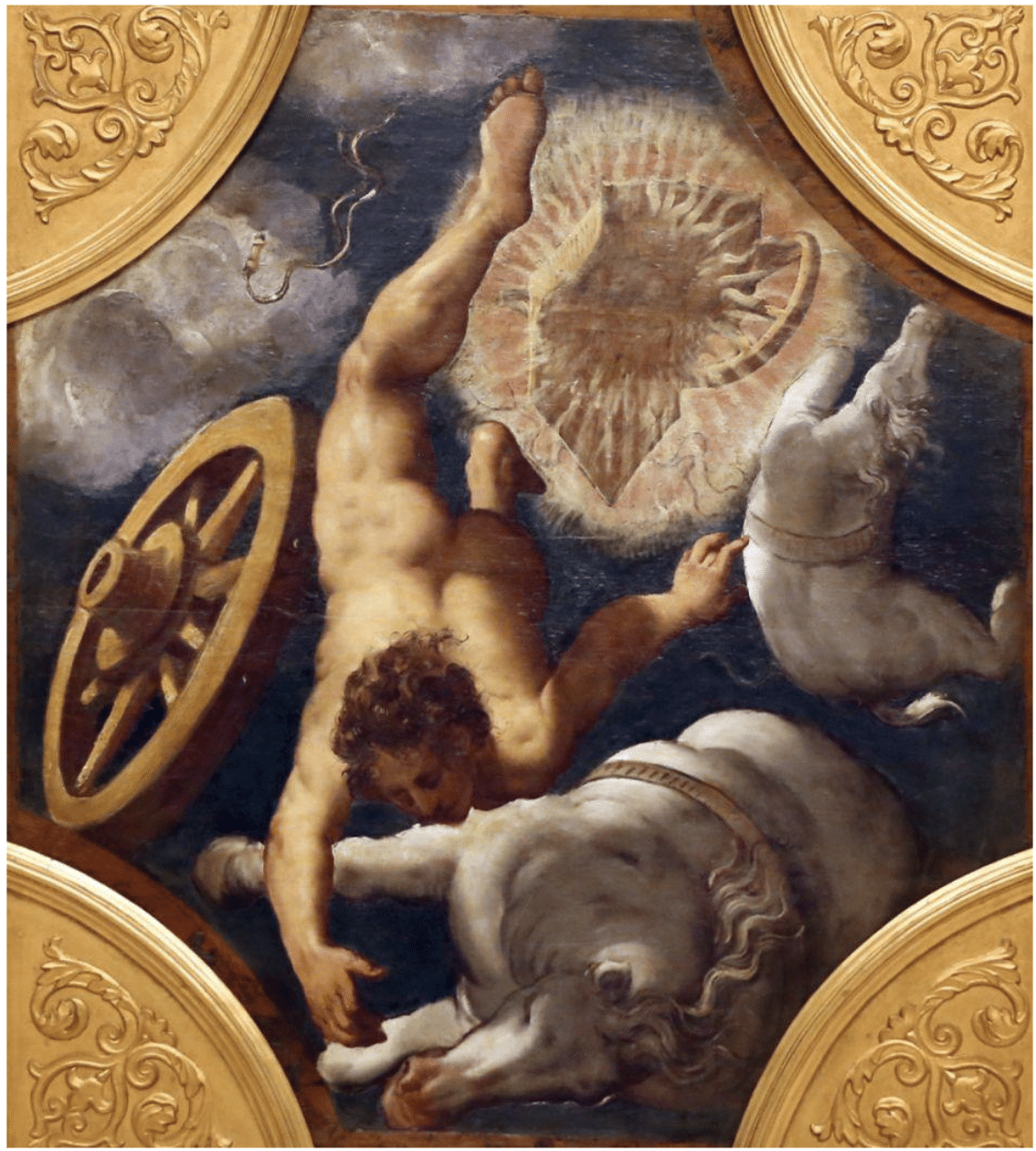

Jacopo Tintoretto (c 1518-1594), Fall of Phaëthon (1541-42) (E&I 18), oil on panel, dimensions not known, Galleria Estense, Modena, Italy. Image by Sailko, via Wikimedia Commons.

Jacopo Tintoretto’s Fall of Phaëthon (1541-42) above, tells the conclusion to this story. We watch as Phaëthon, having lost control of the chariot of the sun and taken a hit from one of Zeus’s thunderbolts, comes crashing towards the earth.

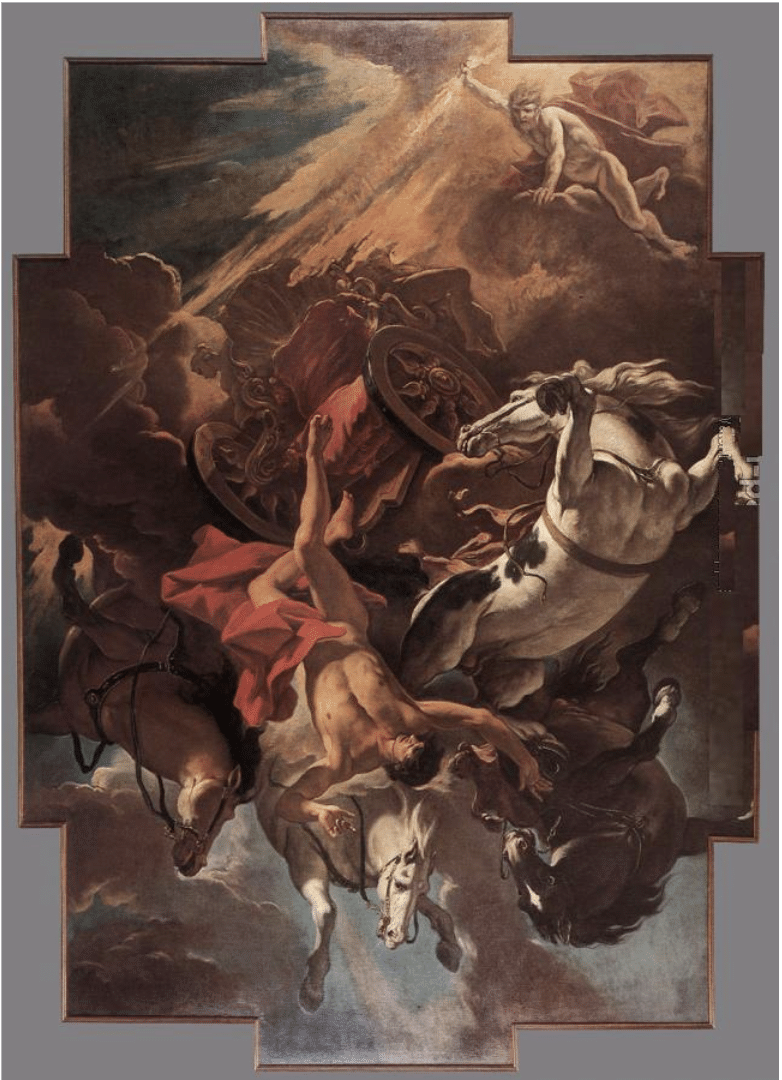

Sebastiano Ricci, The Fall of Phaeton, c. 1699

Late Italian Baroque painter Sebastiano Ricci’s version, above, is a study for a ceiling fresco, so it was meant to be viewed by people looking up. Consequently, Ricci paints the hectic scene in perspective as seen from below: Zeus with his thunderbolt, the upset chariot, the four wild horses, and Phaeton tumbling arms akimbo, as if all are about to fall right on top of us from out of the sky. This is the essence of the Baroque style – an essentially literal realism wedded to high drama, and all of it coming straight at the viewer in stark dark/light contrasts (aka chiaroscuro) and vivid color, as if about to fall right out of the picture frame. What a field day for a figure painter!

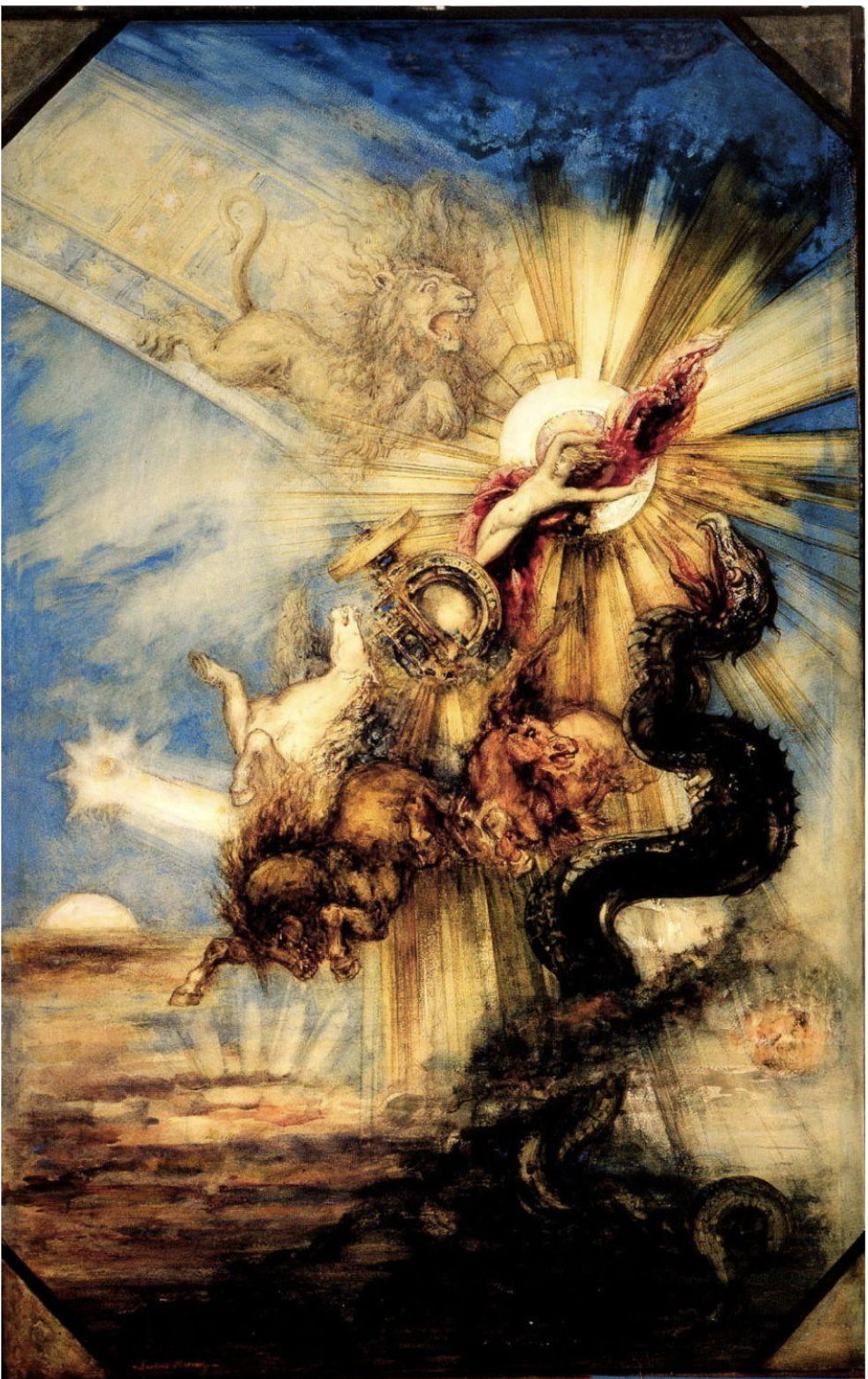

Skipping several centuries ahead and back to where we started in 19th century Paris, in Gustave Moreau’s amazing watercolor The Fall of Phaëthon (1878) everything is searing orange, blazing sunlight, chaos, flame, and mayhem. The sun chariot has just slipped off its zodiac track and is plummeting to the ground, and Phaëthon stands in the chariot in dismay, the horses lurching this way and that. The lion is Apollo, who’s taken that form to pursue the chariot. A huge earth-creature has been set loose from the earth’s opened depths. The moon rises unnaturally on the left as the sun “sets” all too soon.

Gustave Moreau (1826–1898), The Fall of Phaëthon (1878), watercolor, highlight and pencil on paper, 99 x 65 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

Gaetano Previati (1852–1920), Dance of the Hours (1899), oil and tempera on canvas, 134 x 200 cm, Gallerie di Piazza Scala, Milan, Italy. Wikimedia Commons.

If all of these amazing images have whet your appetite for the challenge of painting the human figure, browse through a collection of high quality instructional videos right here. << https://painttube.tv/search?type=product&q=figure*