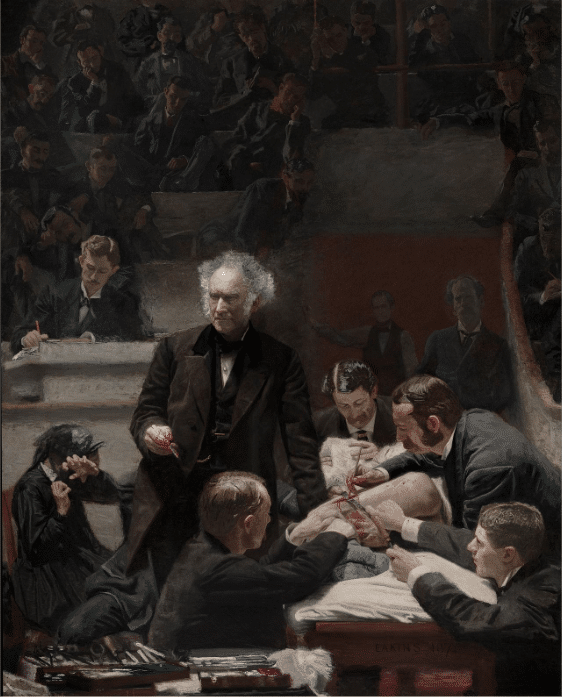

It is recognized as one of the greatest American paintings ever made. The painting is by Thomas Eakins (American, 1844–1916) and it is known as The Gross Clinic (or Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross, as it’s officially titled).s

A young and little-known Eakins created it specifically for Philadelphia’s prestigious 1876 Centennial Exhibition, intending to showcase his talents as an artist and to honor the scientific achievements of his native Philadelphia.

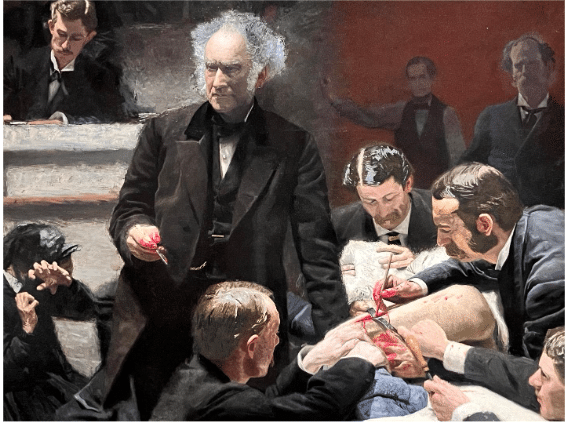

The setting is Jefferson Medical College’s surgical amphitheater. Eakins purposely makes it difficult to tell, but the surgeons are working on the leg of an adolescent boy lying on his side (look for his feet encased in gray socks). The focus, however, is the intense and commanding figure in the center, Philadelphia’s world-famous surgeon and teacher. Dr. Samuel D. Gross is lecturing as he demonstrates for the medical students a procedure that he developed for treating bone disease.

Notice the recoiling woman in the lower left — she is traditionally identified as the patient’s mother. Her cringing, stricken reaction reflects how some of the first viewers of the painting felt too. In contrast, the figure of Dr. Gross embodies the confidence that comes from knowledge and experience. Casting himself as a witness, Eakins can be seen seated over the surgeon’s shoulder, sketching, or taking notes.

There was precedent for such an extraordinary painting from none other than Rembrandt von Rijn’s early masterpiece The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, which was originally created to be displayed by the Amsterdam Surgeons Guild meeting room. Like Eakins, Rembrandt was a young man (aged 25), newly arrived in the city, eager to make a splash. No wonder then that Rembrandt’s anatomical portrait radically altered the conventions of the genre by including a full-length corpse in the center of the image (using Christ-like iconography) and creating not just a portrait but a dramatic mise-en-scène, much as Eakins did after him.

Rembrandt von Rijn, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, oil on canvas, 216.5 × 169.5 cm (85.2 × 66.7 in). (1632). Mauritshuis, The Hague

As it turned out, Eakins’ plan to promote himself and the city of Philadelphia notoriously failed. The fair’s art jury rejected The Gross Clinic, deeming the subject unworthy of fine art and altogether too bloody and brutal for display in the art building. The painting snuck in anyway though, appearing as a prop in a model US army field hospital exhibit. There it provoked one art critic to comment in the Philadelphia Evening Telegraph (June 16, 1876), “There is nothing so fine in the American section of the Art Department of the Exhibition and it is a great pity that the squeamishness of the Selection Committee compelled the artist to find a place in the United States Hospital Building.”

It’s not hard to see why the subject was deemed potentially shocking to viewers unused to seeing such a frightening event depicted in such realistic detail. Bright red blood colors the surgeon’s fingers and scalpel, and the gaping incision is fascinating, repulsive, and confusing because it is so hard to read the position of the patient’s body.

Although some viewers admired Eakins’s command of composition, color, and detail, and praised his convincing creation of form and space, many were repelled. But that same uncompromising realism is at the heart of why this painting is so admired today.

It’s so much more than a portrait – it’s an embodiment, monumental in scale, of the noble cause of reason and science in the communal struggle to wrest control over our lives and bodies from nature.

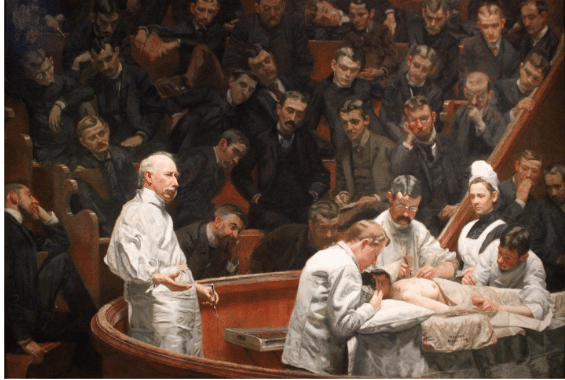

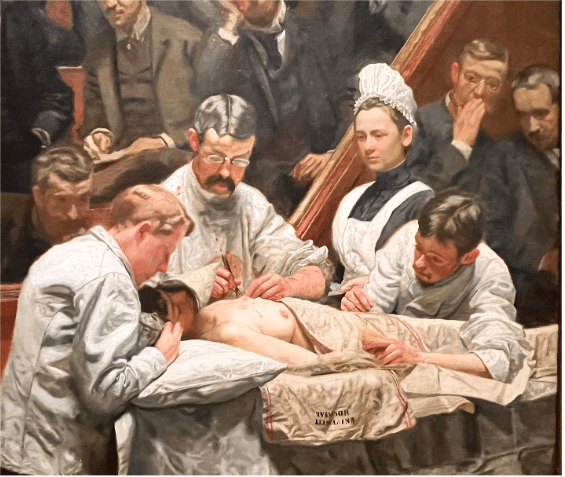

Fourteen years after the controversial Gross Clinic, Eakins was asked to celebrate another great teaching surgeon, the retiring Dr. D. Hayes Agnew of the University of Pennsylvania. Like Gross and Rembrandt’s Tulp, Agnew pauses in the midst of surgery, explaining to his students the mastectomy he has just concluded. Once again, a portrait of the artist appears, at the far right edge of the canvas, this time painted by his wife, Susan Macdowell Eakins.

But everything else is different. Revisiting the subject that earned him his reputation as a ruthless realist, Eakins reconsidered every aspect of the Gross Clinic. He turned the canvas sideways, creating a more even balance between the surgeon and his clinic and drawing the audience of students forward as participants rather than shadowy spectators. Modern artificial lighting makes the setting much brighter and warmer (the Gross Clinic was lit by a stark skylight effect in the dramatic 17th century Baroque manner). Another recent development, the sterile white surgical coat, replaces the street clothing worn by earlier generations.

Thomas Eakins, Portrait of Dr. Hayes Agnew (The Agnew Clinic), oil on canvas, 1889

The fearful mother is replaced by a professional woman on the surgical team, Mary Clymer, one of the first graduates of Pennsylvania University’s new school of nursing. The patient is more legible, if provocatively exposed (Eakins famously insisted there was nothing indecent about the human body), but now the operation is hidden and the blood reduced.

The Agnew Clinic was immediately treasured by the medical school, but public response was cool until the painting was exhibited along with The Gross Clinic at the Chicago World Columbian Exhibition in 1893. The medal Eakins received in Chicago recognizing his artistic achievements marked the turning point in his career.

Postscript:

When it was discovered in 2006 that the Philadelphia Academy of Art had quietly arranged to sell The Gross Clinic for $68 million to a joint ownership by the National Gallery in D.C. and the Walmart family’s Crystal Bridges Museum of Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, the city of Philadelphia sprang into action. Almost overnight, $30 million in donations was raised; a bank loaned the remaining $38 million of the D.C./Bentonville purchase price until the PAA could raise the rest of the funds, which it did, albeit under duress. The painting, one of the most important in America, remained at the Philadelphia Academy, where hundreds of visitors to city view it every day.

For a sense of its scale, The Gross Clinic (above) and The Agnew Clinic, below, as they are displayed at the Philadelphia Academy of Art in Pennsylvania.

If you are interested in learning or improving your skill at painting the figure, check out some of these high-quality teaching videos including classical portraits and traditional oil techniques, and see if something resonates for you.