My teenaged niece has a poster in her room that shows a beautiful painting of natural scenery with two old-fashioned gentleman standing on a promontory that looks out over waterfalls and mountains in the distance.

My niece’s room with her poster of Kindred Spirits (1849) by Asher Brown Durand, a member of the Hudson River school of painters who painted it to memorialize his mentor.

The scenery is imaginary but based on the Catskill Mountains in the Hudson River region of New York. The two men pictured are painter Thomas Cole, (1801-1848), considered the father of American landscape painting, and American poet William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878).

Titled Kindred Spirits, the painting is by Asher Brown Durand (1796-1886). He painted as a memorial upon the death of Cole, who was his friend and mentor. When I first saw the image, it was reproduced on the cover of the Norton Anthology of American Literature, and it was among the first Hudson River School paintings I’d ever seen. I think it was also in a book I once had that paired 19th century American landscapes with poems by Walt Whitman.

Durand was the only student Cole ever took on, and all three men, Bryant, Cole, and Durand, were good friends from way back. Some 20 years before Kindred Spirits, Bryant had invited both Durand and Cole to provide illustrations for The Talisman, a literary annual he started back in 1827.

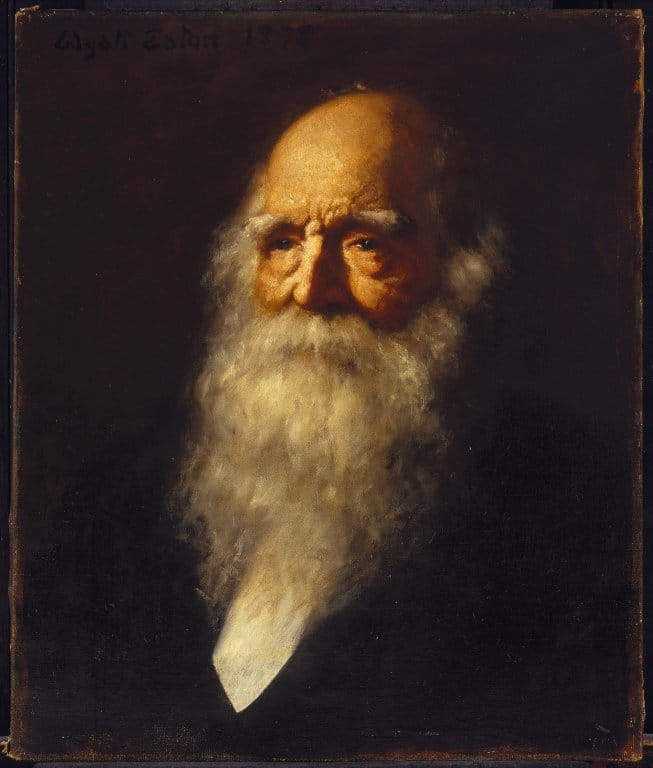

Warren Eaton, Portrait of William Cullen Bryant, 1878, the year he died

In the third issue of The Talisman, which came out in 1829, Bryant published the following poem, To Cole the Painter on his Departure for Europe, in which he urges Cole to take in the Old World’s venerable sights but to stay true to “that wilder image” Cole so masterfully captured of the North American “wilderness”:

![]()

To Cole the Painter on his Departure for Europe

By William Cullen Bryant

Thine eyes shall see the light of distant skies

Yet, Cole, thy heart shall bear to Europe’s strand

A living image of thy native land,

Such as on thine own glorious canvass lies.

Lone lakes – savannahs where the bison roves –

Rocks rich with summer garlands – solemn streams –

Skies where the desert eagle wheels and screams –

Spring bloom and autumn blaze of boundless groves.

Fair scenes shall greet thee where thou goest – fair

But different – every where the trace of men,

Paths, homes, graves, ruins, from the lowest glen

To where life shrinks from the fierce Alpine air.

Gaze on them, til the tears shall dim thy sight;

But keep that earlier, wilder image bright.

![]()

It’s easy to see why this painting gets reproduced so often, isn’t it? For once we have a Romantic painting of lush, unspoiled nature in which the human figures aren’t tiny, insignificant pixels in an overwhelming galaxy of nature run riot. On the contrary, the painter and the poet are featured prominently because they are nature’s translators to the world of humanity, with whom nature is in perfect harmony. In a sense, poet and painter stand in for us, the viewers, inviting us to join them and, in Bryant’s words, “Go forth, under the open sky, and list(en) / To Nature’s teachings.”

Now Part of the Walmart Fortune

Until 2005, Kindred Spirits hung in the New York Public Library as it always had, ever since Durand painted it. When the library decided to sell it to raise funds needed for its “core mission,” a consortium of desperate bidders including New York’s wealthiest major museums, were unable to pool together enough millions to keep it from leaving the state and entering the collection of Walmart heiress Alice Walton, whose resources permitted her to offer some $35 million for the painting.

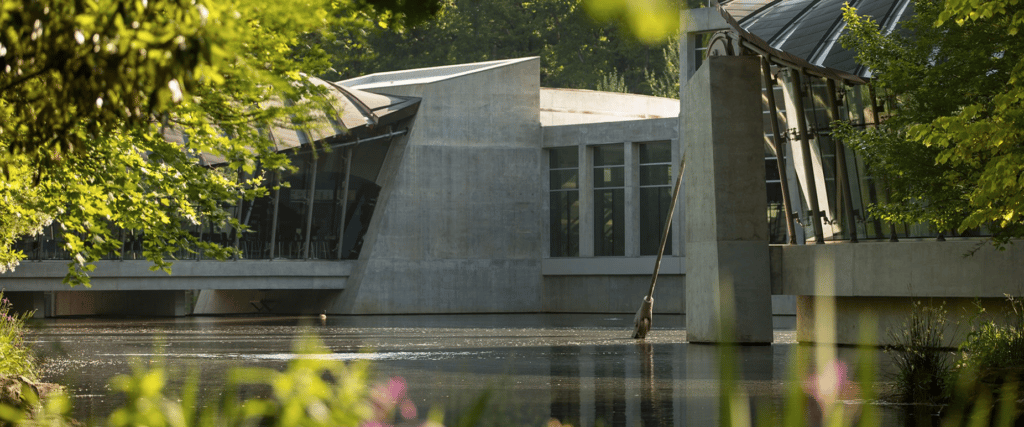

Ms. Walton houses her collection of American paintings in the Crystal Bridges museum in Bentonville, Arkansas.

Crystal Bridges, Bentonville, AK

The whole episode provoked a barrage of outrage and disgust in the New York art-historical world and beyond. On this and other acquisitions by Ms. Walton (including some that violated original agreements that the work never be sold or broken up from a specific collection) the Wall St. Journal opined:

“The Walton Effect is a destabilizing influence in the art world, since Ms. Walton dangles before financially challenged institutions the enticement of an easy, if ethically dicey, alternative to old-fashioned fund raising.” However, the piece’s author, arts writer Lee Rosenbaum, was quick to note that the sword cuts both ways: “To be sure,” she continued, “any institution taking advantage of her ready cash to alleviate its financial difficulties bears full responsibility for violating professional principles.”

Yet, after all the painting is still publicly viewable by the anyone willing to make the trip to the tenth largest city in Arkansa, the Waltons’ (and Walmart’s) hometown.

Cole’s legacy, of course, lives on in American painting to the present day. It’s even being recognized now how deeply (and prophetically) concerned he was about the loss of America’s natural beauty to the encroachments of industrial civilization, already well on its way to effacing, in his lifetime, “that wilder image” of a thriving natural world.

“We are still in Eden,” Cole once said, “shall we turn from it?”

Gouache: the “Opaque Watercolor”

Artist Carla O’Connor works in both watercolor and gouache.

I think of gouache as a sort of hybrid between watercolor and acrylic/oil in that it behaves like watercolor but goes on opaque like those other mediums. Those interested in exploring gouache can catch a free one-hour video demo by Carla O’Connor or peruse instructional DVDs here.

In the paint,

Chris