Today we’re turning aside from painting to visit a popular form of sculpture called assemblage. An assemblage is a sort of 3-D collage, wherein an artist puts together (assembles) various elements to create a new three-dimensional image or object.

Joseph Cornell, a solitary man who lived a seemingly ordinary life in mid-twentieth century America, helped invent the genre using material he collected on his daily walks through New York City and environs. Through his work Cornell repeatedly revealed the miraculous properties of the commonplace, ultimately gaining international acclaim and “conquering the art world from his mum’s basement,” as one writer quipped.

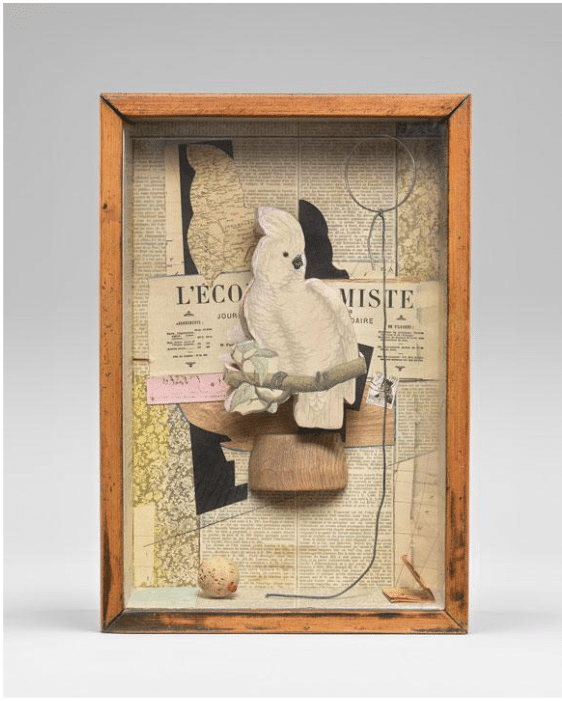

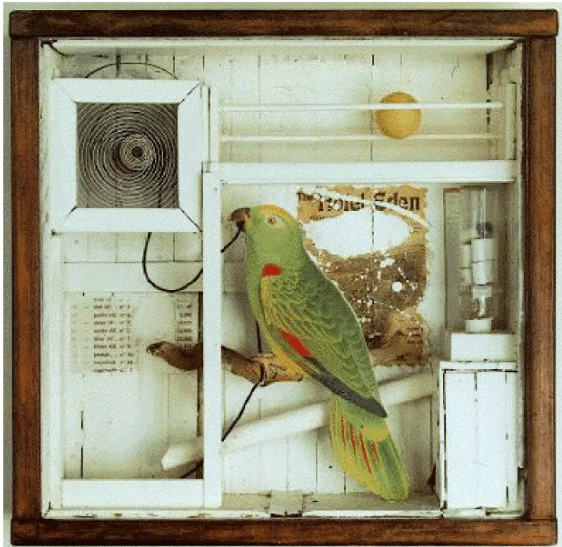

Joseph Cornell, “A Parrot for Juan Gris,” assemblage, 17 3/4 x 12 3/16 x 4 5/8 in. (1953–1954)

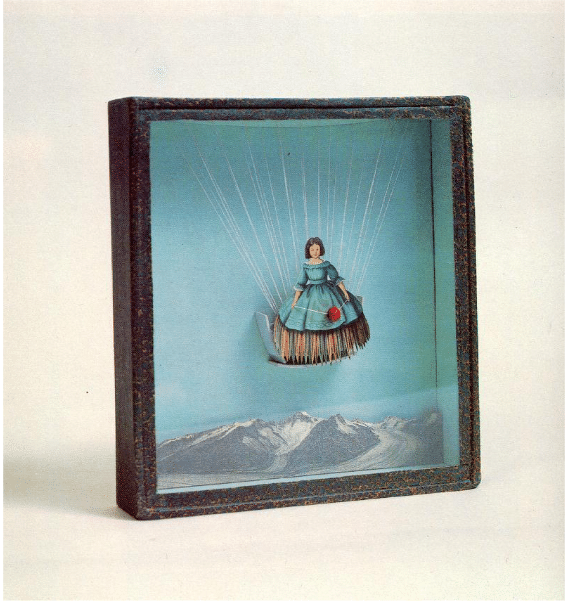

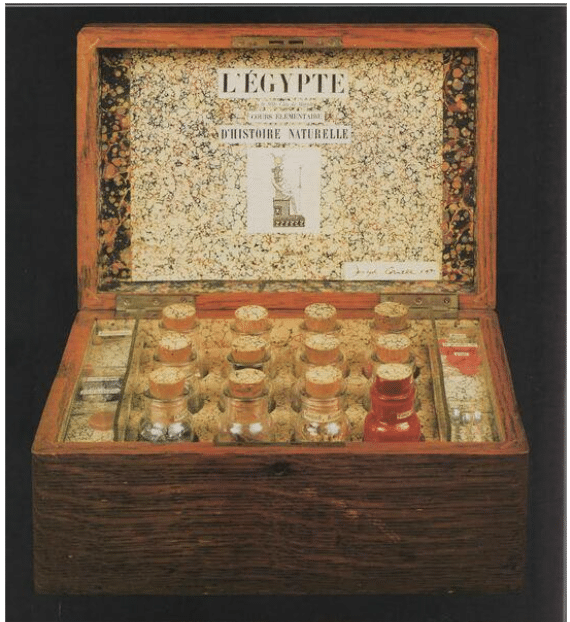

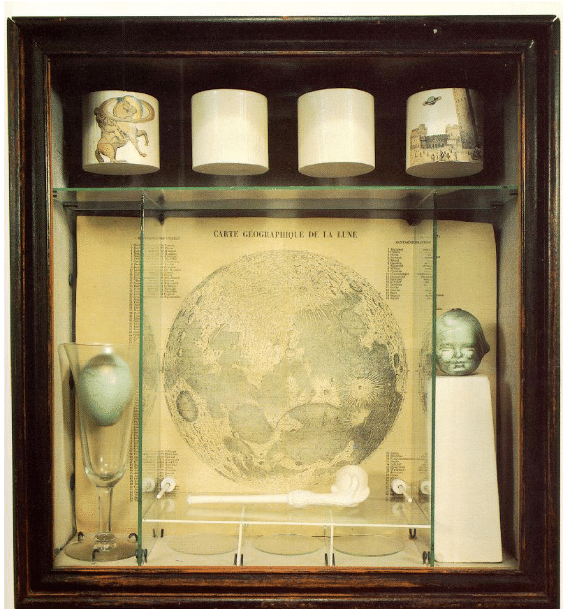

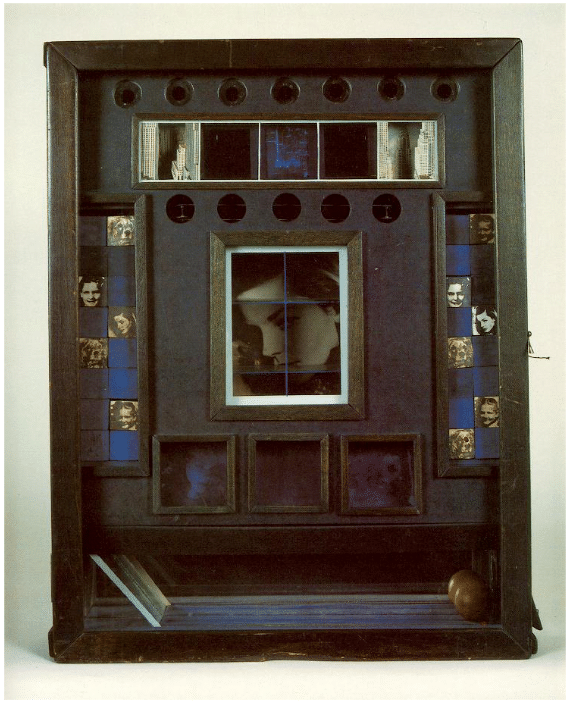

Cornell is revered for his unclassifiable “boxes,” most created during the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s. Cornell’s boxes are something like surreal, glass-fronted dioramas – shadow boxes containing startling, intriguing, and mysterious combinations of objects that, taken together, resonate with inexpressible poetic associations.

Peering into one of Cornell’s boxes, you might find a doll surrounded by a dense forest of cut branches, or a white ball spattered with gray paint like tiny craters on the moon, a white broken clay pipe bowl in visual rhyme with the sphere, amid scraps of faded wallpaper and cut-out illustrations of planets, constellations, and stars.

“Perhaps the ideal way to observe the boxes is to place them on the floor and lie down beside them,” writes poet Charles Simic in the book he wrote about the artist and his work, Dime-Store Alchemy, The Art of Joseph Cornell. “It is not surprising that child faces stare out of the boxes and that they have the dreamy look of children at play,” Simic continues. “Theirs is the happy solitude of a time without clocks when children are masters of their world. Cornell’s boxes are inviting us, of course, to start our childhood reveries all over again.”

Joseph Cornell, “Tilly Losch,” 10 x 9 1/4 x 2 1/8 in. (1935)

Though his work is endlessly intriguing, Cornell lived a quiet, anonymous life with his disabled mother in Flushing, NY, supporting them both by working in Manhattan first as a textile salesman and later as a designer. On lunchbreaks and walks to and from his mother’s house, he collected the unwanted odds and ends with which he constructed tiny universes – treasure boxes full of veiled and secret worlds with vast poetic overtones.

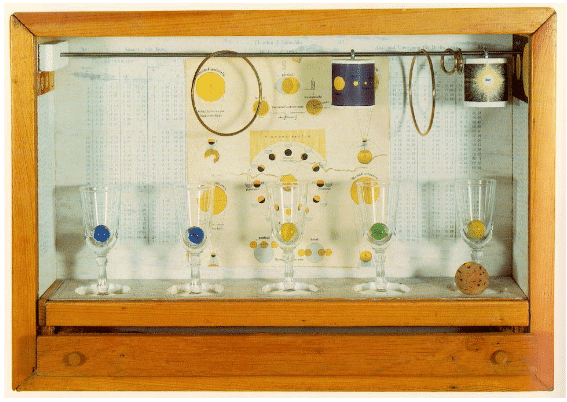

>Joseph Cornell, L’Égypte de Mlle Cléo de Mérode, (1940)

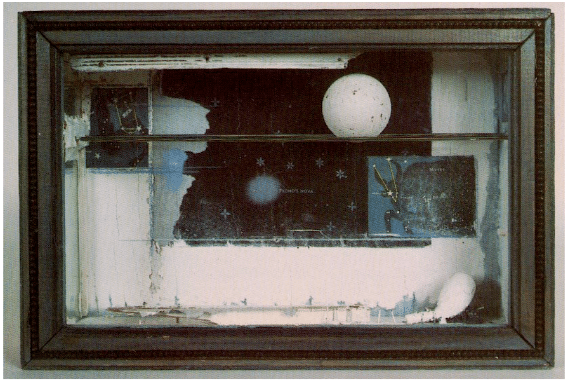

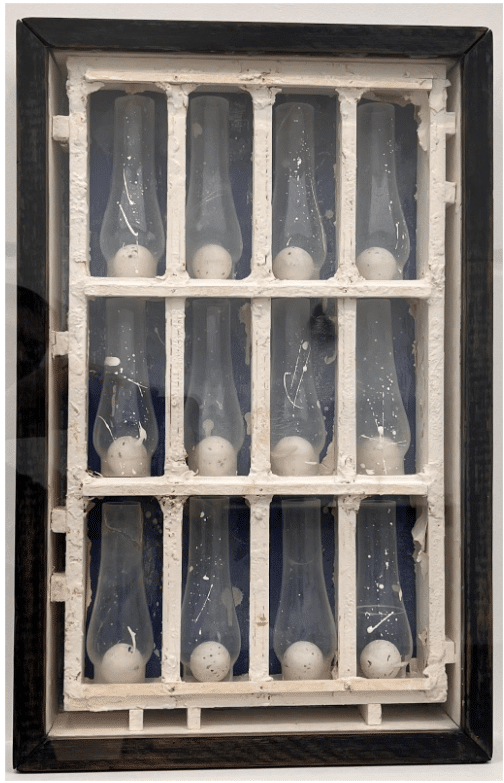

The assemblage below is titled “Observatory American Gothic.” It’s one of the modern/contemporary art holdings of the Philadelphia Academy of Art. At first glance, it appears very modern indeed,

Joseph Cornell, “Observatory American Gothic,” 17 9/16 x 11 5/16 x 2 11/16 inches. (Around 1954). Philadelphia Academy or Art.

Looking longer and closer, we find the work is constructed of seemingly random, yet oddly related, time-worn objects. It’s structured like a barred window or the façade of the old Brooklyn tenement buildings, covered with yellowed and peeling paint. So we have ideas of observation and home.

At the same time, it suggests a curiosity cabinet or a laboratory: science beakers containing specimens categorized on shelves. In each compartment, or “window” sits an antique lamp-glass, or flue, given paint splatters resembling little night skies with white streaking comets, orbiting planets, and shooting stars.

At the base of each glass “vessel” sits a solitary ping-pong ball like an isolated moon – or a speckled egg. The far-flung associations cluster, from the commonplace to the cosmic: science, the passage of time, dilapidated city apartment buildings, astronomy, songbirds, flight, prisons, lamps that long ago lit someone’s way in the dark.

Why we should care

Cornell’s enigmatic constructions of found objects are more than quirky collages. Cornell played with the way ideas get associated with visual elements and objects the same way ideas cluster around the images brought together in poems. Cornell’s boxes are at once playful and profound – they eloquently suggest that the world is beautiful but ultimately unsayable.

Art that isn’t made but found perforates the boundary between art and life. The objects Cornell made, “memory boxes” or “poetic theatres,” as he called them, exhibit not only aesthetic beauty and charm but also mysterious partly obscured narratives that convey messages beyond what meets the eye, visual poems about things we cannot see: ideas, memories, fantasies, and dreams.

The lesson is one we must learn again and again: the commonplace is miraculous if rightly seen. “The question is not what you look at but what you see,” as Henry David Thoreau wrote in his journal.

It’s for these reasons that at least one example of Cornell’s highly original work is a required holding for any major museum in America.

Joseph Cornell, L’Egypte de Mlle Cleo de Merode cours, assemblage (1940).

After Cornell, many contemporary artists began, and continue, to combine fragments of the stuff of everyday life, past, and present, to form fascinating works of art and new images.

Cornell’s work in particular can seem to reflect the “American experience” by rescuing the “wretched refuse” of decades past and recombining them into a melting pot of suggestive new forms. “America is a place where the Old World shipwrecked,” poet Charles Simic writes. “Flea markets and garage sales cover the land. Here’s everything the immigrants carried in their suitcases and bundles to these shores and their descendants threw out with the trash.” Thus, Cornell’s boxes, he says, “contain the poetry of our age.”

Joseph Cornell, Untitled (Penny Arcade Portrait of Lauren Bacall), 20 1/2 x 16 x 3 1/2 in. (1946)

What Kind of Man was Joseph Cornell?

“What kind of man is this,” asker painter Robert Motherwell in 1953. “who, from old brown cardboard photographs collected in secondhand bookstores, has reconstructed the nineteenth-century ‘grand tour’ of Europe for his mind’s eye more vividly than those who took it…[who] can incorporate this sense of the past in something that could only have been conceived in the present?”

This is the kind of man, answers Kate Mendillo, writing about Cornell’s “Pink Palace” for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, who “lived on a street called Utopia Parkway, whose childhood hero was Harry Houdini, the ultimate master of escape and transformation. A man whose art insists that we privilege poetry and imagination over cynicism.”

Joseph Cornell, Untitled (“Pink Palace”), wooden box containing photostat with ink wash, wood, mirror, plant material and artificial snow. 8 5/8 x 14 ¼ x 4 3/8 in. Ca. 1950. SFMoMA.

On “Pink Palace,” above, Kate Mendillo writes, “Joseph Cornell draws back the sparkling blue curtains in this untitled work to reveal tiny actors engaged in a great drama on the steps of a grand but decaying hotel or palace. A sheet of mirror lining the back of the box reflects the viewer, but the reflection is fractured.”

The Art Institute of Chicago has a large collections of Cornell boxes, and you can zoom in on high-resolution images of more than 40 of Cornell’s works here or visit the Art Institute’s Website<https://www.artic.edu > and search Cornell’s name.

Joseph Cornell, The Hotel Eden, assemblage, approx. 15 x 15 x 4 in. (1945) source: slideshare.net