Nineteenth-century American painter Martin Johnson Heade achieved popular success with paintings of the flat salt marsh regions along the East Coast. His humble landscape subjects set him apart from those contemporaries who pursued more dramatic vistas of the American wilderness such as, say, Thomas Cole or Thomas Moran.

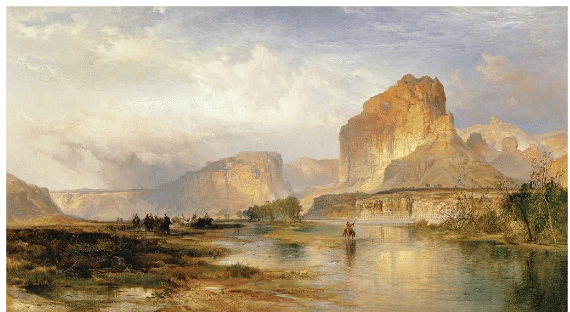

Moran set out as part of the Hayden Expedition of 1871 with the goal of documenting Yellowstone, but he was floored by the sight of cliffs rising above the town of Green River, Wyoming.

Thomas Moran, Cliffs of Green River, Wyoming. Oil, 25 1/8 x 45 3/8 in.

1874. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Combining the skills of scientific and topographical illustration with a sensitive, painterly style and unique color palette, his painting “Cliffs of Green River” (above) captures the changeable colors of the multicolored, sedimentary bluffs towering above the river, while the dizzying reflections of the cliffs meeting the open sky semi-dissolves the foreground in light. Representations of the craggy, unfamiliar landscape of Wyoming captured the imagination of the United States, which increasingly associated its national identity with the untrammeled wildness of its western territories.

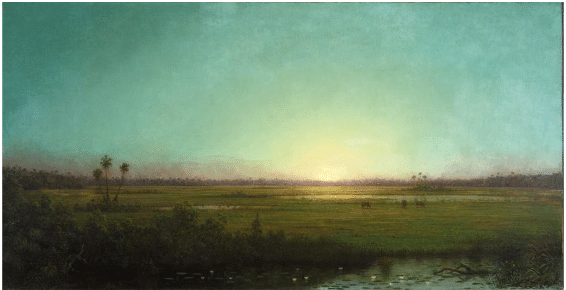

But Heade went his own way. Along with the artists known today as Tonalists, Heade’s work featured the effects of light and atmosphere, often with a limited palette, evocative of mood. Heade’s many marshes make use of horizontal compositions of striking simplicity.

Martin Johnson Heade, Florida River Scene, c. 1889

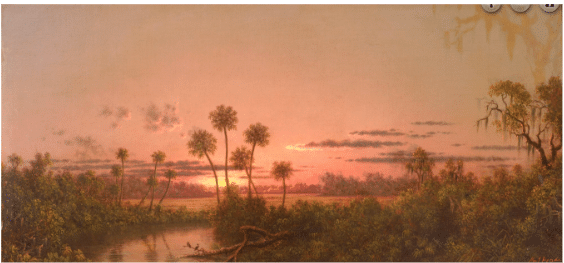

During the 1880s, American industrialist and railroad magnate Henry Flagler invited Heade, along with other popular American artists (including Maine landscapist Maria a’Becket) to escape the northern winters as artists-in-residence at his numerous luxury hotels in Florida, including three in Saint Augustine alone. Flagler needed ways of selling Florida as a vacation destination (so that folks would use his railroad and hotels), and installing artists to hobnob with gilded age vacationers was a successful ploy.

One of industrialist Henry Flagler’s Florida luxury hotels.

Heade painted “Twilight” (top of page) in Saint Augustine, where he settled permanently in 1884. Some art historians see in “Twilight” and others like it a reflection of the transitional mood of what Heade called “our worn-out country” after the Civil War. There certainly is a stark contrast between Heade’s backlit, late-in-the-day meditations and the cinematic grandeur of paintings Moran produced, though both were painting after the war.

The difference is in the approach to the role of painting and the feeling each artist channels into the work. Moran’s grand painting of Wyoming is a nostalgic fantasy of a site that had already been transformed by progress. Moran returned in memory to the same geological landmark in more than 40 canvases over a period of some 30 years. But when he created his panoramic “Cliffs of Green River” in 1874, the landscape was already a major rail crossroads. Only in his mind’s eye did it remain a landscape untouched by colonization and industry. Heade’s marshes too rely on artistic intervention. Unspoiled landscapes like the ones Heade painted in Florida were already beginning to vanish and fill with encroaching houses and hotels.

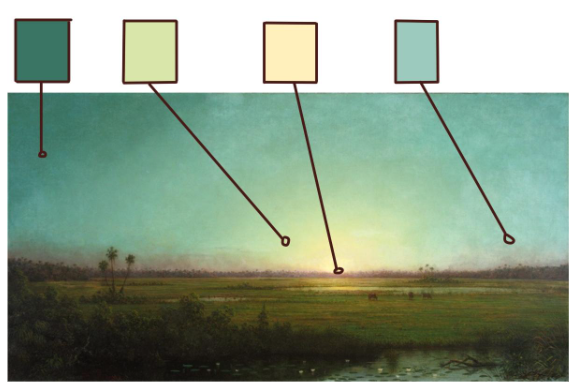

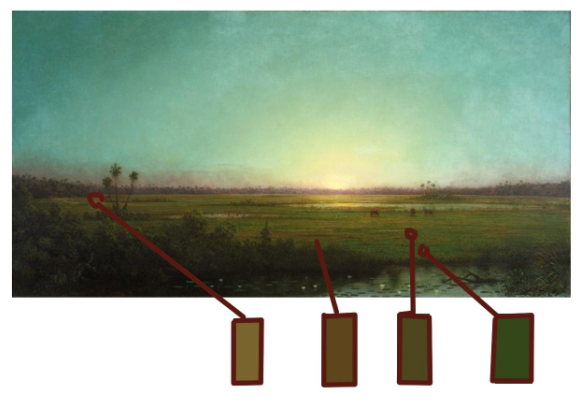

Heade painted his skies with color mixtures of his own concoction. Perhaps at first glance you assumed the painting at the top of the page had a blue sky, a blue with some green in it like Prussian or phthalo blue? I certainly did, but Scientific™ analysis proves otherwise. As the swatches called out of the painting below make clear, we’re actually dealing with a variety of bluish shades of green and yellow, with only the hue on the far right even coming close to approximating “light blue” as we usually think of it.

Because the green in the sky is very different from the orange-tinted green in the foreground, we assume it’s on the blue end of the spectrum, even though we’ve just seen that it isn’t. Colors “change” based on the other colors they’re near or next to. Painters say when this happens in landscape such as Heade’s that “the sky reads as blue;” we “read” it as blue because that’s how we process it visually.

In the selection below, you can see that only a small percentage, if any, of the foreground is a “true” (think rainbow-spectrum) green; most of it is a species of ochre, or olive green with orange-yellow mixed in and warming it up considerably. Heade was an especially adventurous colorist.

“Heade was the first artist of national repute to make his home in Florida,” says Thoman Graham of Flagler College. “He brought the Hudson River school to the St. Johns River. An avid outdoorsman, he spoke out for preservation of the state’s natural resources both in his writings and, most memorably, in his magnificent landscape paintings….”

“The history of Heade’s career in Florida is, like many Florida stories, a complicated interplay between the forces of tourism and development and the rich natural beauty of the state,” says the publisher of the art historical study, “Martin Johnson Heade in Florida,” by Roberta Smith Favis.

In that book, Favis closely examines Heade’s relation to the evolution of tourism in St. Augustine and uses (Heade’s) writings to show his conflicting attitudes toward development and conservation. Heade “artistically celebrated the beauties of the state being touted as “the new Eden,” but he was an active participant in the projects of Henry Flagler to transform St. Augustine into a mecca for northern tourists, while his writings expressed concern that the pristine environment and its inhabitants were already threatened.”

There’s an interesting video on the subjects and colors of Florida that you might like titled CARL DALIO: IN THE FLORIDA KEYS.

You might also be interested in learning more about color mixing and color theory with Johnnie Liliedahl’s Understanding Color video.