The Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944) is best known for his vivid depictions of love, anxiety, sorrow, and death. Raised in a religious household, and impacted by the early loss of his mother and sister, the artist has always been understood as an isolated and melancholy figure who battled mental illness for much of his life.

Like Vincent van Gogh, Munch animated nature in his works both to express psychological states and to celebrate the abundance and vitality of the cosmos. His landscapes often ponder the mysteries of existence and humankind’s interaction with and impact upon nature and vice versa.

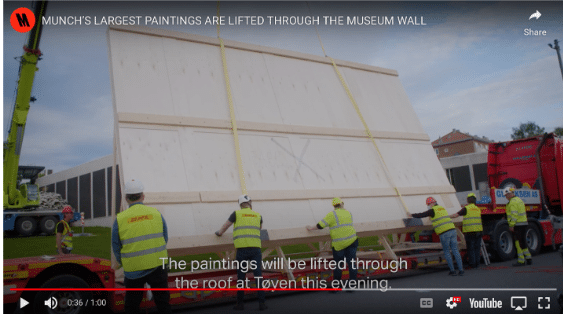

The largest of Edvard Munch’s Sun paintings has just completed an extensive journey from Museum Barberini in Potsdam, Germany, and is currently undergoing installation at MUNCH, the new Munch Museum in Oslo, Norway. Transporting the painting to the exhibition room was a massive undertaking, involving cranes, construction crews, trucks, boats, and airlifting through the museum’s wall to get it in.

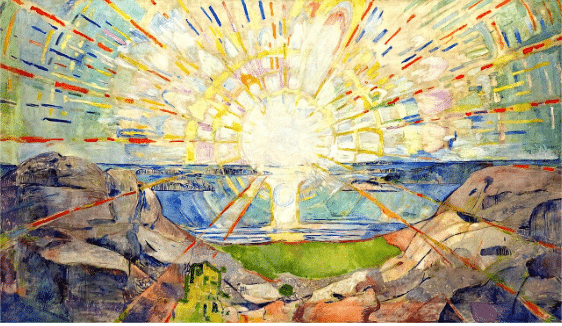

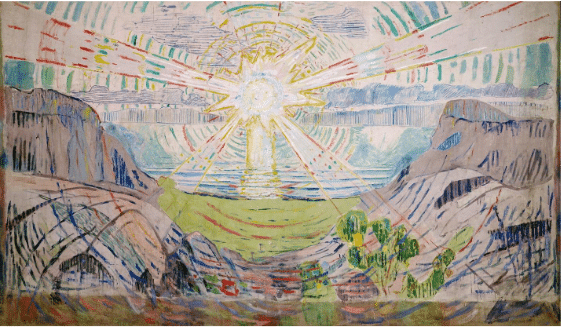

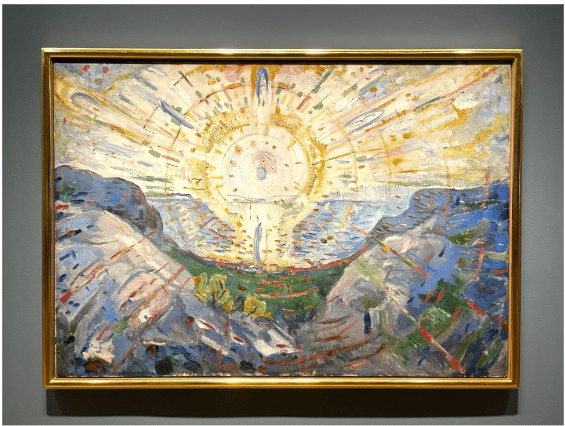

One of the other versions of Edvard Munch: The Sun, 1910–11. Oil on canvas. Photo © Munchmuseet.

The University of Oslo, which owns one of the most vividly colorful Sun paintings (pictured at the top of the page), sees in it “The university’s fundamental task – enlightenment – expressed as a majestic sunrise… The painting radiates light, warmth and nature: a monumental, yet realistic depiction of the force of life and creativity. In thick layers of paint and with strong, bright colors, Munch pulls us into his vision of light and enlightenment.”

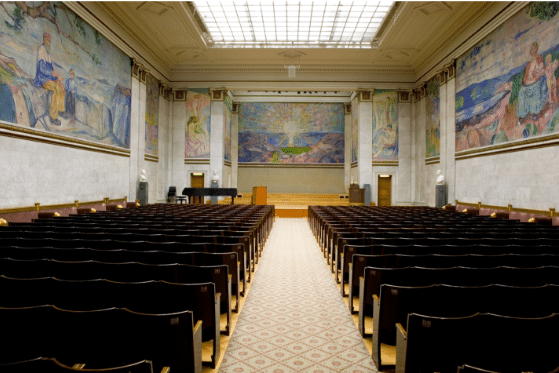

“Trembling Earth” will feature three versions of The Sun spanning approximately 3 by 5 meters. It is exhibited in the vibrant yellow room named ‘Beneath the Sun’ – which brings together 11 early versions of the visionary paintings Munch made for the University of Oslo’s Aula in 1911.Here’s the museum’s time-lapse video of the installation process:

The international exhibition has garnered rave reviews in both Germany and USA. The New York Times hailed it as one of the best exhibitions of last year. Now, “Trembling Earth” is approaching the conclusion of its journey, culminating in a dramatic finale in the artist’s hometown.

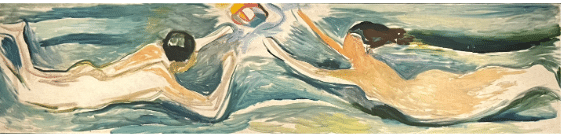

“The sun has been roasting hot all day, and we let it roast [us]. Munch has done a bit of work on a swimming painting, but for most of day we were lying around, overwhelmed by the sun, in deep sand dunes right down by the edge of the fjord, between the big boulders, and letting our bodies drink up all the sun they could bear. No one is bothered about swimming costumes here, the gentle gusts of a warm July wind are the only fabric between us the sun.”

“This is how Christian Gierløff, a close friend of Edvard Munch, described some scorching summer days he shared with the artist in 1904. One can almost feel the life-giving force of the sunbeams on one’s body when reading his words. One may have a similar experience when encountering Munch’s monumental masterpiece The Sun, which depicts a glowing sunrise over the rocky archipelago off Kragerø.” – MUNCH museum

Munch’s work deliberately goes against the grain of pictorial tradition. For his mature work, the artist chose a simplified pictorial language over European realism, because he wanted to be sure his paintings had the impact of primeval symbols rather than function as decoration. In other words, Munch’s style assures his work must be understood for what it says about humanity and nature and not how beautifully or realistically it portrays them. That is where Munch’s work gets its power – from a marriage between its consciously raw stylization and the sense the artist put into it, of nature as an uncontrollable, sometimes almost alien force, akin to existentialism’s struggle with the void underlying human reason.

The Sun’s forever home, The Aula, The University of Oslo. Photo: Jaro Hollan © Munchmuseet

These paintings are meant to be more than just representations of a sunrise over the rocky Norwegian coast. Like most of Munch’s work, they have strong symbolic overtones at their core. In the case of the Sun paintings, these overtones have to do with ideas about earthly and physical well-being, spiritual centering, cosmic connection, and the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, much of which audiences of Munch’s time would have understood immediately.

Painted symbolically to be suggestive of the eternal and the universal, The Sun reflects Munch’s interest in nature and Vitalism, a school of scientific thought that promoted health, hygiene and physical education, and that emphasized the sun as an energy-giving force.

The influence of Vitalism extended into most areas of society, from sport and physical culture to philosophy, literature and the visual arts. The term derives from the Latin word vitalis, which means “of or belonging to life”, and the movement was based on the idea that all living organisms have a special living, or vital, force.

Edvard Munch, The Sun, on exhibit at the Clark Institute last year.

One of the other two paintings Munch painted of the Sun in 1911 is owned by the Clark Art Institute in Massachusetts. It was exhibited as the centerpiece of an amazing show of Munch’s landscapes there in 2023.

Read more and watch videos about the installation process on the museum’s website, here.

“Trembling Earth” is co-organised by MUNCH, Museum Barberini and The Clark Art Institute.