Evidence has been put forward that a group of teenage boys who persecuted van Gogh, led by a rich kid with a cowboy fixation, may have accidentally shot the artist in the stomach while playing with a loaded gun. It took hours for the artist to die of the wound.

Despite what everyone has always said, the famous “symbolically charged” Wheatfield with Crows (1890) was not van Gogh’s final painting. In fact, his last was Tree Roots, a fascinating painting for its near abstraction, but one that suggests nothing about death or despair. On the contrary, it was discovered a few year ago that Andres Bonger, Theo’s brother-in-law, wrote in 1893 that “the morning before his death he had painted an underwood, full of sun and life.”

“Tree Roots,” 1890, believed to be Van Gogh’s last painting

“Tree Roots,” 1890, believed to be Van Gogh’s last painting

Actually, the artist’s life was looking up. A few months earlier he’d received his first review by a critic, and it was an overwhelmingly positive one. He had just put in an order for new paints, brushes, and canvas for work he had planned.

Additionally, there was no note (a “possible suicide note” found in his pocket turned out to be the draft for an upbeat letter he’d sent to his brother a few days prior). And it’s well known Vincent didn’t own a gun.

None of the eye-witness accounts of his death confirm that he shot himself, not even Vincent. When asked if he had wanted to kill himself, he remained vague, and all he said was, “I think so.”

“Almond Blossoms”, 1890. Not a trace of morbidity here, another one of the paintings Vincent completed in the last three months of his life.

In the 2011 book Van Gogh: The Life by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith include a meticulously researched appendix referencing a 1950s interview with one Rene Secretan. In 1890, he was the 16-year-old son of a wealthy Parisian family staying the summer at Auvers-sur-Oise, where Van Gogh was staying when he died. Secretan was the ringleader of a bunch of teenage boys (including his older brother) who regularly harassed, ridiculed, and cruelly pranked van Gogh.

That summer, Secretan was under the spell of the “Wild West” craze. He’d seen the Wild Bill Cody and his Wild West Show in Paris and regularly ran around in a cowboy costume. His getup included leather chaps and a loaded, small caliber pistol he used to kill rabbits and squirrels.

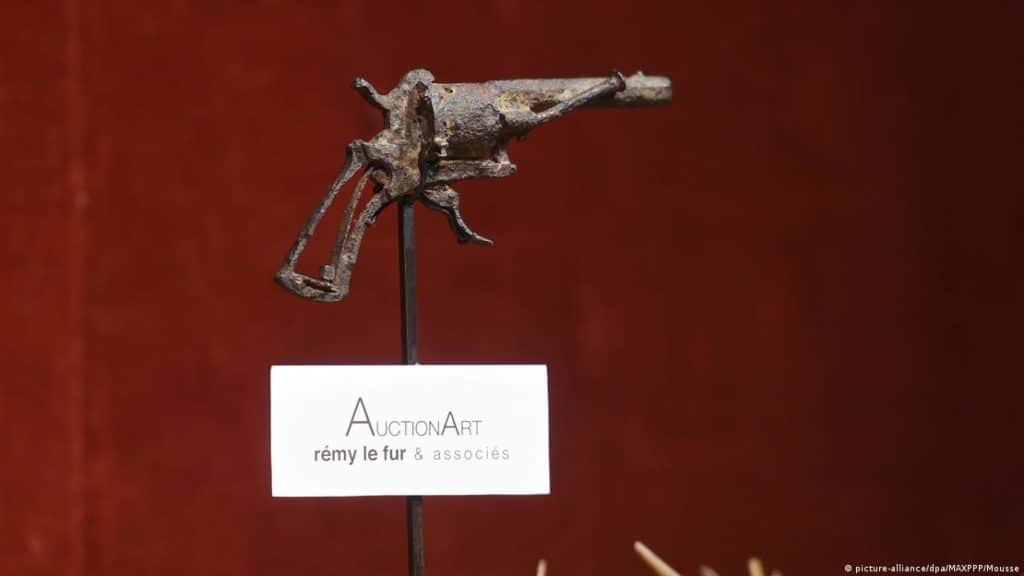

A farmer tilling a field near where van Gogh died in 1890 dug up a rusted low-caliber pistol in 1965. It auctioned for $180,000 a few years ago as the one that killed van Gogh.

Shortly before he died, aged 83, in 1957, Secretan told a French interviewer about the Van Gogh he had known, a man “more like a tramp” than the vigorous genius he had seen portrayed by Kirk Douglas in the film “Lust for Life” the previous year.

Secretan admitted, in detail, his abusive behavior towards Van Gogh but was vague and inconsistent on the artist’s death. He claimed he’d learned of it only from a Paris newspaper – itself a suspicious statement, since no newspaper is known to have printed anything about it.

Secretan grew up to become a well-respected banker and businessman (and an expert marksman). He said of the gun, “It worked when it wanted. It was just ‘fate’ that it wanted to work the day it shot van Gogh.” But why was he so sure it was that gun (his) that killed the artist? There was an extensive search for a gun at the time, and after all nothing was found until eight years after Secretan died.

It would not be out of character for Vincent to protect the boys (one of which, Secretan’s older brother, he knew well and was fond of) by keeping what happened to himself. Maybe he felt resigned to how things played out, maybe even grateful for an end to his struggles.

Why wasn’t the weapon found at the time, despite an extensive search? If van Gogh had dropped or thrown it, it would have been easy to find. It was eventually found underground – did the boys bury the pistol before fleeing the scene of the accident? In his dying days, Secretan claimed he never knew what became of the gun, because he’d given it to one of his mates and left for Paris earlier that day.

In 2013, the late Dr Vincent Di Maio, one of the world’s leading gunshot forensic experts (he examined the bullet wounds of Lee Harvey Oswald and Trayvon Martin) reviewed the newly uncovered research. Di Maio concluded that Vincent could not have shot himself.

For one thing, Di Maio said, firing guns in those days was a very messy affair, with black powder ending up all over the shooter’s hands, none of which was found on Vincent’s hands or clothing. Noting the odd location (stomach) and angle of the bullet’s entry, as well as Dr. Gachet’s description of the wound and the absence of powder burns, Dr. Di Maio pronounced a finding of homicide, concluding that the shot had to have been fired from about two feet away.

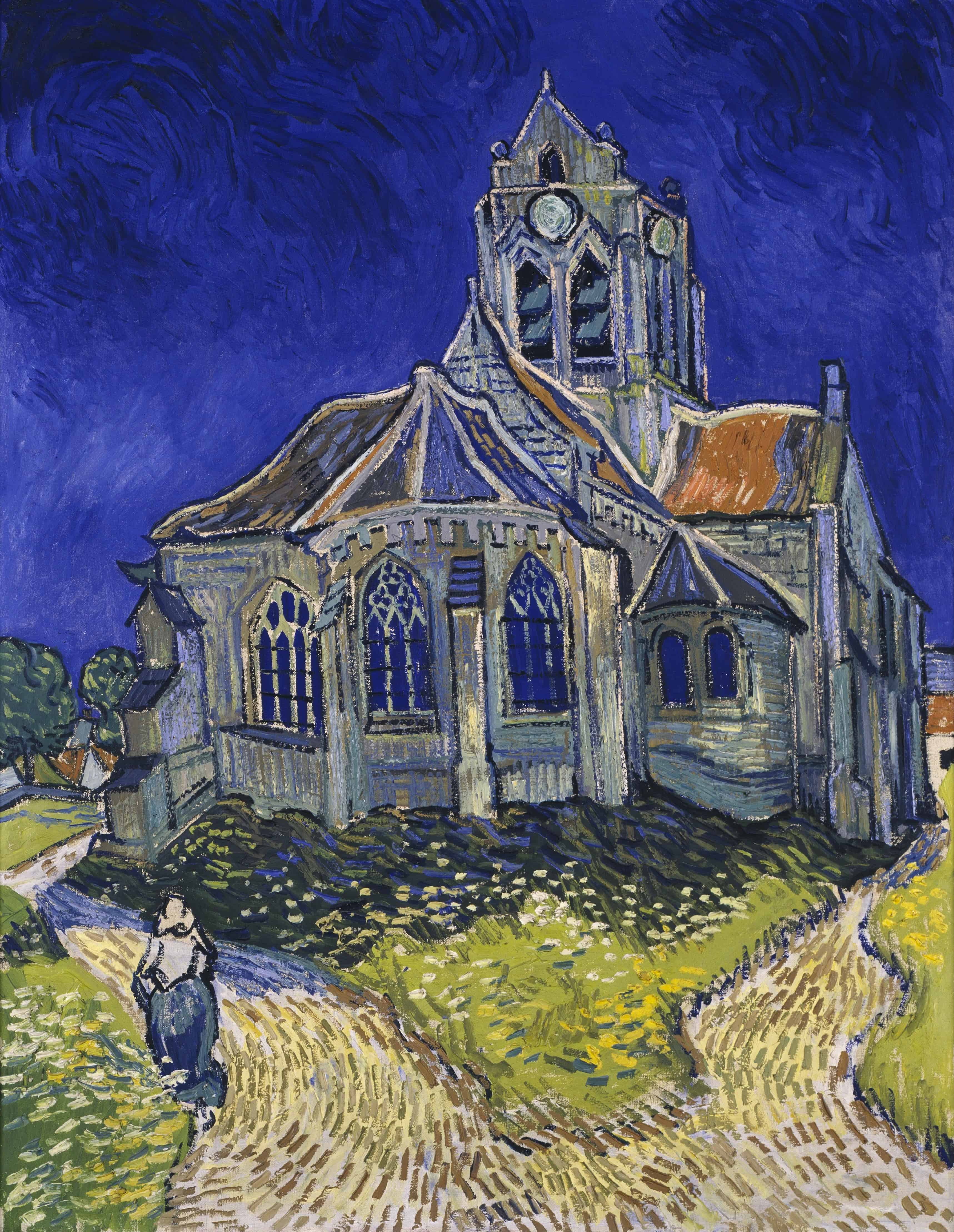

“The Church at Auvers,” 1890, another one of the last paintings

“The Church at Auvers,” 1890, another one of the last paintings

Why isn’t all this common knowledge? Perhaps because a lot of van Gogh fans and scholars simply don’t, or don’t want to, believe it. Most of the official trustees and members of the van Gogh family reject the theory.

Evidently, powerful documentation and expert testimony are not enough to change beliefs that have been strongly held for more than a century,

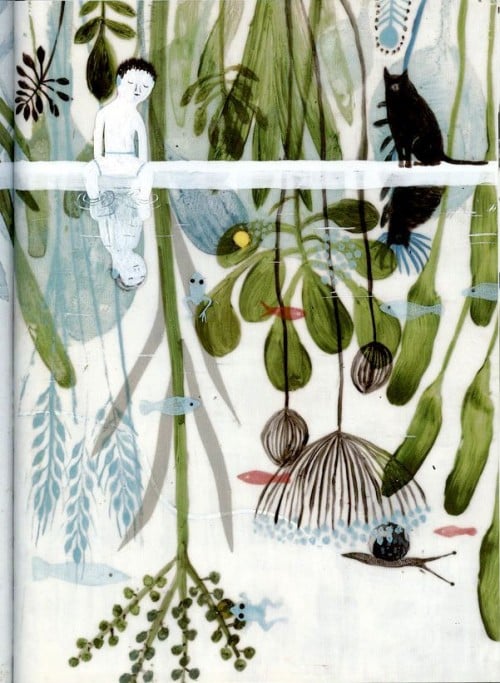

Into the Wild

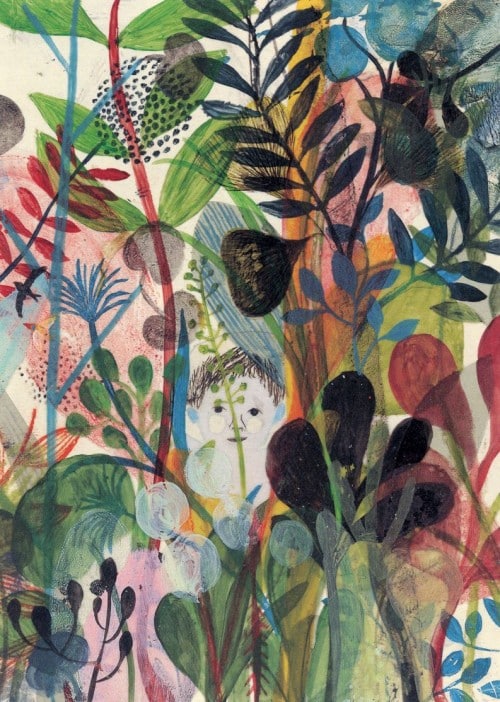

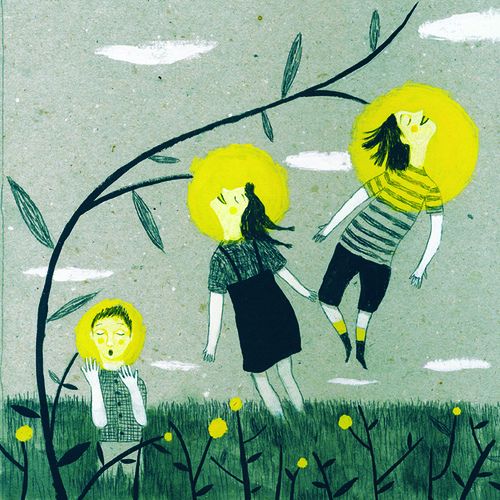

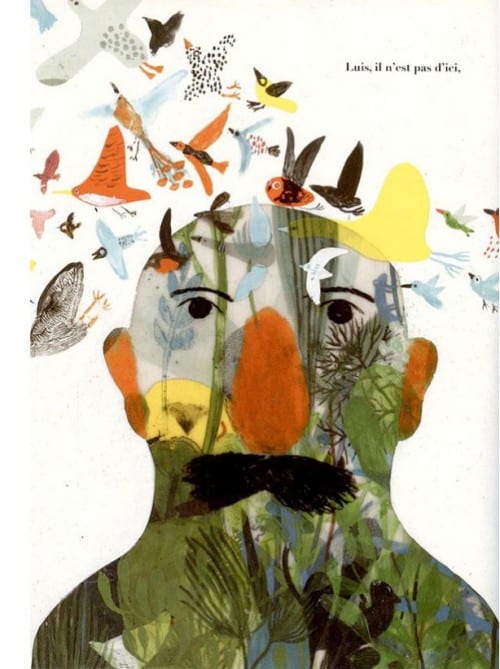

Violeta Lópiz has illustrated for newspaper and children’s books, but her work transcends simple illustration by evading any single interpretation or straightforward narrative. Her characters often paradoxically appear simultaneously lost and at one with their natural settings. Originally from Ibiza, Spain, Lópiz lives and works in Peru. The selection of works here are from a book called Les poings sur les îles, a collaboration with author Elise Fontenaille. Many more examples of her richly imagined, charming and magical work may be found on her blog.