Today we continue our recent Inside Art spotlight on this important American artist, and we begin with a poem by Emily Dickinson.

We grow accustomed to the Dark—

When Light is put away—

As when the Neighbor holds the Lamp

To witness her Goodbye—

A Moment—We uncertain step

For newness of the night—

Then—fit our Vision to the Dark—

And meet the Road—erect—

And so of larger—Darknesses—

Those Evenings of the Brain—

When not a Moon disclose a sign—

Or Star—come out—within—

The Bravest—grope a little—

And sometimes hit a Tree

Directly in the Forehead—

But as they learn to see—

Either the Darkness alters—

Or something in the sight

Adjusts itself to Midnight—

And Life steps almost straight.

When this poem was written, Emily Dickinson and the artist James MacNeill Whistler, who were close contemporaries, were aged 32 and 29 respectively. For the poet, 1862 was a hard year, a difficult period of loss and struggle for meaning. The sense of her poem, with its dusky atmosphere and its veiled sense that life is ultimately an enigma, takes a very modern, almost “noir” position – life “almost” plays it straight. (To see this poem come alive, watch this two-minute animation by Hannah Jacobs.)

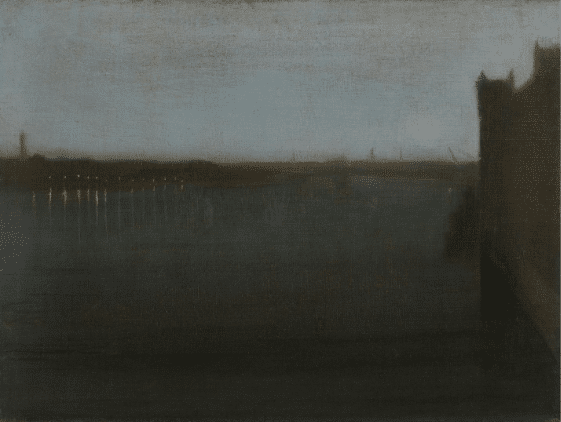

Nine years later, in 1871, Whistler painted his first nocturne. It was a view across London’s Thames (Whistler, who was born in Lowell, Mass., was a European transplant) rendered in a strangely flattened, atmospheric haze that wasn’t Impressionism, nor strictly realism, but altogether something else, and something unmistakably “modern” at that.

James MacNeill Whistler, Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Chelsea, 19.8 in × 23.9 in (1871)

Whistler coined the term “nocturne” as applied to landscape paintings of night scenes. He borrowed it from the piano works of Chopin, largely to emphasize that his paintings didn’t contain uplifting, sentimental messages or the sort of religious or moral content then expected to somehow “improve” the viewer. Rather, like music, Whistler’s nocturnes (a series of nighttime views of the Thames at Battersea between 1870 and the mid-1880s), were to be appreciated as purely beautiful, emotive objects without “story,” without symbolism, and without any moral dimension whatsoever. Though just the way we do things now, at the time for many this was a disturbingly “modern” notion upsetting centuries of European aesthetic theory.

For artists, it’s worth asking what inspired Whistler to make these breakthrough paintings. Where did such strikingly new and unique work come from? The answer is partly Whistler’s creative intelligence and partly excellent timing.

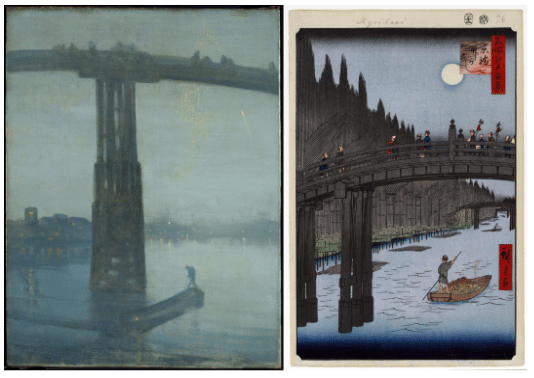

The nocturnes owe their existence to the Japanese art of the period, which also influenced many of the French Impressionists and post-Impressionists such as Gaugin and van Gogh. Whistler took Impressionism’s disregard for objective accuracy and combined it with the flattened, silhouetted forms typical of sumie-e Japanese printmaking. The monochromatic color washes, indirect lighting, visible brushstrokes, distinctive scale and perspectives, and above all the flattening of the picture plane all echo sumi-e. Even Whistler’s use of his pictographic ‘butterfly’ signature, imitating a traditional Asian/East Asian “chop” seal (most visible in the center of the bottom edge of the painting above) points to his sources.

Nearly all of the viewing public didn’t know it, but Whistler even borrowed compositional ideas wholesale from the earlier Japanese prints, as you can see from the side-by-side comparisons below. This is what’s known as “stealing like an artist.” Such is the nature of creativity – putting together already existing elements in new ways to say something authentically your own. (Personally, I find it a reassuring relief when, as with a supposed “genius” creator like Whistler, you get to look under the hood and realize once again that nothing is created in a vacuum.)

Left: Whistler’s Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge, oil on canvas, 1872-1875 and Right: Utagawa Hioshige, Bamboo Yards, Kyobashi Bridge from One Hundred Views of Edo, woodblock print, 1857.

This was something new to Western art. Whistler himself saw his nocturnes as a move towards abstraction, into the timeless, purely aesthetic zone of “art for art’s sake.”

“By using the word ‘nocturne,’” the artist later explained, “I wished to indicate an artistic interest alone, divesting the picture of any outside anecdotal interest which might have been otherwise attached to it. A nocturne is an arrangement of line, form, and color first.”

He used other musical terms too, such as symphony, harmony, study, and arrangemen.t It all emphasized the work’s tonal (another musical term) and formal qualities and downplayed the narrative motive.

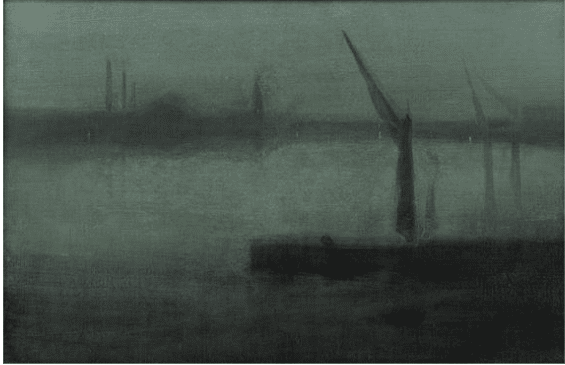

James McNeill Whistler, Nocturne (c.1870-1877)

Nonetheless, Whistler deeply understood that he was striking a nerve – what was in these paintings was in the air, something people felt but rarely found words for: the sense of peering into the murky future and the uncertain transformation of the world by rapid industrialization, all as if seen in a dusky vision, shot through with a “dreamy, pensive mood.”

James McNeill Whistler, Nocturne in Blue and Silver, Battersea Reach (c.1870-1875)

When these paintings were first shown, English art writer John Ruskin, the most prominent and influential critic of the day, savaged them mercilessly. Perhaps the most famous of the series is a depiction of fireworks titled Nocturne in Black and Gold – The Falling Rocket (below). Ruskin condemned this work specifically:

“I have seen, and heard much of Cockney impudence before now,” Ruskin said, “but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.” Whistler, an opportunistic master of self-promotion, very publicly sued Ruskin for libel.

James Abbot MacNeill Whistler, Nocturne in Black and Gold – The Falling Rocket, oil, c. 1872-5

The trial, held in the summer of 1877, was a sensation. Over the two-day hearing many figures from the art world gave evidence and the popular press discussed the nature, definition, and value of art. Whistler’s painting had subverted the old guard, and as art historian Ernst Gombrich puts it, Whistler “felt called upon to fight the battle for modern art almost single handed.”

Under cross examination, the artist was asked whether he could really demand such a high figure for a painting that had probably only taken a couple of days to paint. He replied “No, I ask it for the knowledge of a lifetime.,” which ever since has been a favorite saying of working artists, whether or not they know (or care) who said it first.

Whistler won the case, though he was awarded just a farthing for damages and refused costs. The Nocturnes, brought into the court upside down and ridiculed in the press, were now unsaleable. Whistler was subsequently declared bankrupt. Ruskin was appalled by what he saw as Whistler’s moral victory and resigned his professorship at Oxford. The fallout from the case affected Ruskin and Whistler for the rest of their days. (And no wonder Whistler titled his autobiography The Gentle Art of Making Enemies.)

James McNeill Whistler, Nocturne (c.1870-1877)

Today Whistler’s nocturnes are recognized for, as one commentator wrote, their “fundamental human truths in the face of new and terrifying powers” and above all, “of nostalgia in the face of progress.” They were a primary source of the heavily atmospheric, misty, moody style that became known as late 19th century Tonalism. And they were and still are the seed of who knows how many of the nighttime paintings we casually refer to as nocturnes today.

Esoterica

Whistler’s process seems pretty foreign to contemporary painting. It is described in detail by his biographers:

“His method was to go out at night[…] stand before his subject and look at it, then turn his back on it and repeat to whoever was with him the arrangement, the scheme of colour, and as much of the detail as he wanted. The listener corrected errors when they occurred, and, after Whistler had looked long enough, he went to bed with nothing in his head but his subject. The next morning, if he could see upon the untouched canvas the picture, he painted it, if not he passed another night looking at the subject.”

He painted them by creating an extremely fluid “sauce” that allowed him to build up thin layers of luminous color, sometimes one right over another, while the lower layer was still wet. The exact recipe of the mixture is unverified, but it was reportedly so thin and fluid that the wet canvas sometimes had to be painted flat on the ground so the image wouldn’t slide off!

Carl Bretzke, Boatyard, Quarter Moon, oil on canvas, 12×16 in.

If you’d like to learn how to paint nocturnes of your own, you might want to look into Carl Bretzke’s video course, Nocturnes: Painting the Night.