Art historians use the term Tonalism to describe an American artistic movement spanning from about 1880 to approximately 1920. More generally, the term (tonalism or tonalist with a lower case “t”) describes a style of painting in which color range is limited so that subtle gradations of the middle values (aka color “tones”) constitute the primary aesthetic and means of expression.

But the timeline stretches further back. Historical tonalism is most firmly rooted in the French Barbizon style which sprang to life as early as the 1830s. These painters were in rebellion against French mainstream art as academic pseudo-realism catering to wealthy buyers.

Barbizon painting, the Roots of Tonalism: Théodore Rousseau, The Forest in Winter at Sunset, oil on canvas, 1846-67

They were the first true plein air painters. The Barbizon painters (so named for the rural town, well outside Paris, where they set up shop) rejected the contrived artificiality and stuffiness of the “official” painting of the Paris Salon and took their easels out into the country to paint the total opposite: country life at its most honest and unassuming.

Barbizon painters such as Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, Jules Dupres, created ordinary, undramatic landscape scenes, loosely painted to emphasize with mood, feeling, and suggestion. They dumped the French Academic trappings of Biblical stories, political propaganda and mythological goddesses, satyrs, and nymphs en masse. Instead, the Barbizon painters painted the raw beauty of the gnarled trees, wet rocks, rippling waters, and rugged rural communities in and around hilly Barbizon and the neighboring Forest of Fontainebleau.

In the Barbizon mode: Théodore Rousseau, The Edge of the Woods at Monts-Girard, Fontainebleau Forest, oil on canvas, 1852-1854

Where Did Tonalism as We Know it Come From?

Starting in the 1880s, young post-Civil War American landscape painters, inspired by the hints and innovations of a few older-guard pioneers (e.g. William Morris Hunt, George Inness), made the trip by steamer to France. There they took inspiration from the exciting developments in avant-garde landscape painting sparked by the Barbizon School.

The approach to landscape painting that would be known as Tonalism arose from a fusion between the mid-nineteenth-century Europeanlandscape painting the expats encountered and the late nineteenth-century American landscape developments they found when they returned.

From the beginning Tonalism seemed closely related to musical composition (c.f. George MacNeil Whistler’s titles referencing the “nocturne,” a musical term minted by Chopin) and poetry (American Tonalist progenitor George Inness originally included poems with his paintings, to the bafflement of critics).

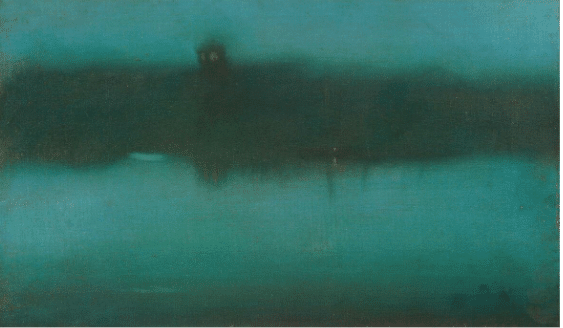

James MacNeil Whistler, Nocturne in grey and silver, 1873.

Whistler, an American with French aesthetic sensibilities living and working in London, demonstrated some of Tonalism’s most radical possibilities. Inness, an American landscape painter with a deeply mystical vision, created work that became the prototype.

George Inness, Home of the Heron, 1893, Chicago Institute of Art

To the younger generation of American artists, the work of Innes, Barbizon and its stepchild Impressionism held radical new theories of painting offering a more inward-looking approach than the grand, stylized Hollywood blockbusters of Bierstadt, Church, and the rest of the Hudson River School – for which the public was rapidly losing its taste after the rude awakenings of the Civil War.

By the 1880s, and for the next 30 or 40 years, the spirited, intimate Tonalist landscape established a new chapter of American art.

Low-toned, softly edged atmospheric landscape painting resonated with the time as well as the transcendentalist literature of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Additionally, an important role was played by the visionary, otherworldly canvases of American originals Ralph Albert Blakelock and Albert Pinkham Ryder, the latter of which taught landscape painters that “the artist should strive to express his thought, not the surface of it.” It’s worth remembering that a young Jackson Pollock cited Ryder as “the only American master” that interested him.

Albert Pinkham Ryder, WITH SLOPING MAST AND DIPPING PROW

c. 1880 – 1885

Albert Pinkham Ryder, Near Litchfield, Connecticut, 1876

“In terms of Tonalist subject matter and vision, the landscapes of the pathbreaking artists Ralph Blakelock and Albert Pinkham Ryder were crucial in the development of a distinctly romantic, if not a spiritual or quasi-religious element,” as Cleveland succinctly puts it. “Mystery, dream, memory, and imagination are often espoused in their haunting, broadly painted canvases of dusk and moonlight.”

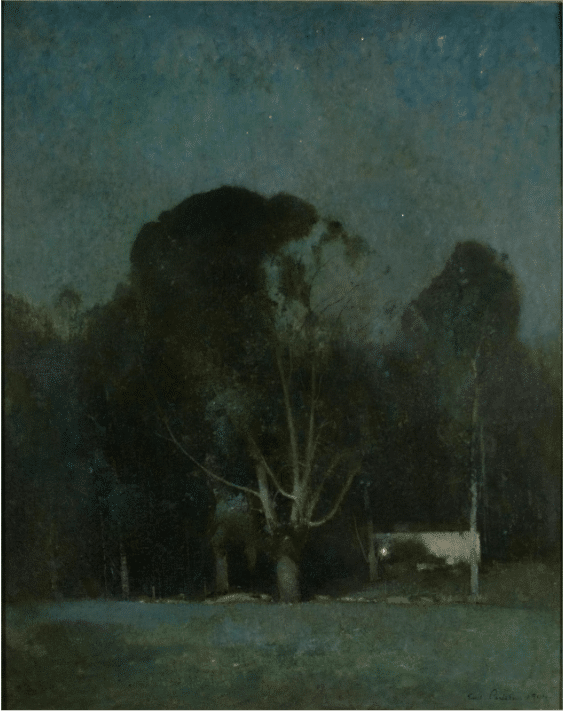

Emil Carlsen, Night, Old Windham, 1904.

Tonalist landscape painting began to take a backseat to far more colorful Impressionism and then abstraction, the latter taking root when European modernism hit Boston, Chicago and New York in the Armory Show of 1913. After about 1920, it was no longer a dominant stream of American art, and Tonalism drowned, along with respect for the Hudson River School and realism in general, in the tsunami of modern and abstract art.

Throughout the subsequent decades, the actual works of the historical Tonalists disappeared from view. Scores of expressive landscapes by the likes of Homer Dodge Martin, Bruce Crane, Dwight Tryon, and J. Francis Murphy languished in obscure texts and museum storage rooms (many are presumably still there). Major institutions deaccessioned their work along with that of their predecessors, the nineteenth-century Hudson River School painters.

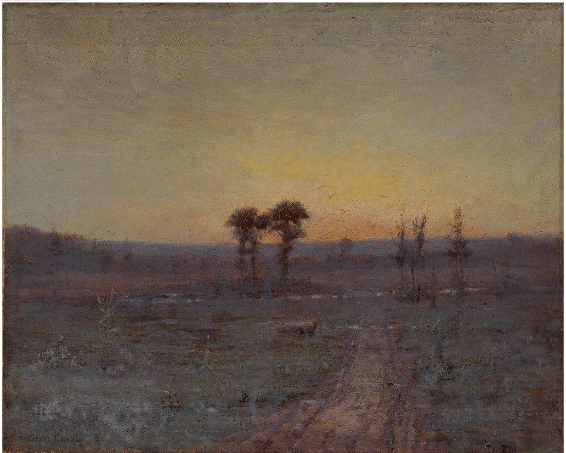

George Glenn Newell, Twilight, c.1905

Although general interest in the Hudson River painters revived from about 1980, it took David A. Cleveland’s landmark 2010 study of the period (A History of American Tonalism: 1880-1929, Hudson Hills Press, Manchester, Vermont) to spur widespread contemporary interest (primarily among working artists) in traditional Tonalism.

To its original practitioners, Tonalism probably seemed at the time both radically new and, in its poetic evocations, eternally relevant. Perhaps they were not wholly mistaken, for a vital, younger generation has risen to meet them and carried their flag into our own times.

Unknown Artist, circa 1900.

Today there’s widespread interest, and the philosophy of painting behind Tonalism continues to inform a splendid variety of work.

If you’re interested in learning how to add tonalism to your own artistic practice, contemporary painter Mary Garrish vas a video in which she shows you how to enhance emotions in your paintings using a limited palette and a simple method to create “poetic” paintings. This video contains everything you need to know about Tonalism and how to paint in the style. Whether you paint en plein air or in the studio, Mary will share her methodical approach to painting so that you too can create wonderful scenes just like her, no matter the landscape.