An occasional series all about analyzing what makes paintings beautiful, iconic, memorable, or effective.

Painters, beginners and masters alike, make leaps and bounds by studying creative triumphs of the art. What kind of principles, techniques, compositional designs or color choices have artists used to create your favorite paintings?

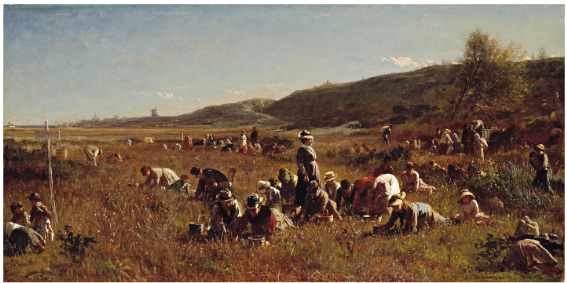

Nineteenth-century American painter Eastman Johnson is probably best known for his realist paintings of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, especially his depictions of workers during cranberry harvests there.

Eastman Johnson, The Cranberry Harvest, Island of Nantucket, 1880, oil on canvas, 69.5 x 138.4 cm (27-3/8 x 54-1/2 in.), Putnam Foundation, Timken Museum of Art

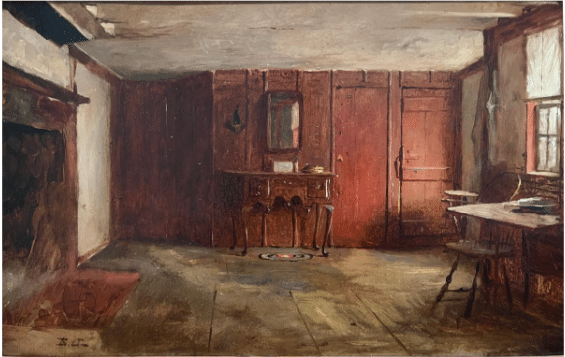

Johnson was working squarely in the realist mode when he painted “The Other Side of Susan Ray’s Kitchen” (top of the page) in 1875. He was already becoming one of his era’s best-known American artists, known for paintings that told stories of everyday life (a mode called genre painting). Though it’s “just” a beautifully rendered rural interior, “The Other Side of Susan Ray’s Kitchen” (I’ll call it “Susan’s Kitchen” for short) there is in fact a story under the surface, should you choose to read it.

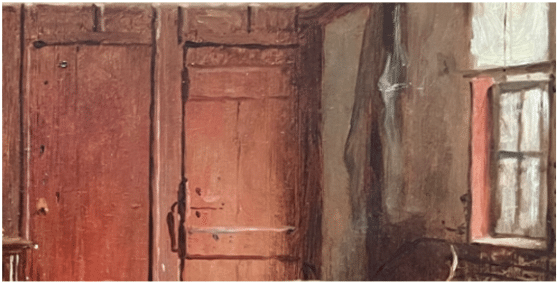

DETAIL, Eastman Johnson, The Other Side of Susan Ray’s Kitchen, oil on panel, 1875.

Asking ourselves why Johnson painted this particular work at the time that he did can help us inhabit the work, to see what it feels like from the inside and what it has to offer if we take the time to get to know it.

What strikes us first is the feeling he creates, the result of an outstanding coordination of color, line, and artistic intention. Susan’s Kitchen presents us with an empty interior lacking visible human drama and sans the studied refinement his 1870s audience might have expected otherwise. Why?

Let’s look closer at what we’re given. It’s a long-format horizontal painting, which allows Johnson to emphasize the somewhat stark but mildly lit space squeezed between ceiling and floor. The lack of decoration, and the single chair and food pan on the right-side table, suggests to us the inhabitant (“Susan”) lives here alone, hermit-like, in an old place likely to be far away from the city or anyone else. From the light we might say it is, perhaps, early morning, the gray start of a new day.

The limited palette harmonizes and softens the scene and, if you like, begins to tell a story: Rough paint handling, coarse brush-handle scratchings, and humble, earthy colors (nothing flashy, just neutrals, ochres, a smidge or two of blue, and a chalky Venetian red it looks like) bespeak a stripped-down, no-nonsense day-today life.

By joining everything together with this pleasing, harmonious palette, Johnson dampens potential harshness or any sense of the unfortunate. Despite everything, the other side of Susan’s kitchen is an appealing, if rough-and-ready, and above all American sort of place – a strong clue as to why Johnson painted it and what it’s all about.

Even absent the figure, through the sum of its composition, color, and paint handling, Susan’s Kitchen suggests more than a simple kitchen: it evokes a sense of American life as a stronghold of practical, hardened endurance.

How’d He Do It?

For all its draftsman-like linearity, there’s nary a straight line here. Everything is bent, worn, bulging, sagging, or scuffed, the edges and surfaces scratched, gouged, and uneven. Nothing is new or even in decent shape – nothing except for an expensive-looking piece of “Chippendale” furniture against the back wall, right smack in the middle of the painting. But wait – What’s that doing here?

Chippendale was a sort of luxury style with an elaborate “fancy” look popular in the British colonies during the 1740s. The look was very English – and at a time when political tide in the colonies was turning against the Empire, the wealthy folks who bought them were also being Royalists – showing support for the Monarchy. So, when Johnson painted Susan’s Kitchen, he did so knowing his viewers would see a reference to colonial America, if not the Revolutionary War.

In fact, there seems to be a deliberate contrast between the room’s only two pieces of furniture, emphasized by the different way Johnson handled the paint as he represented them. On one side of the room there’s that fancy antique Chippendale. On the other, we have a crude and far more utilitarian table, rude but ready, complete with a bent metal pan.

The Chippendale Mystery: what’s that fancy piece of bedroom or drawing-room furniture doing in this rough-around-the-edges kitchen?

Such odd bedfellows probably could only have been seen together under one roof in just this time and place: America in the late nineteenth century. As it happens, the nation at the time, having recently put behind it another traumatic war – the Civil War – was again redefining itself.

Painters like Johnson, Thomas Eakins, and Winslow Homer rolled up their sleeves and bent their brushes toward describing an America torn but toughened by what it had been through.

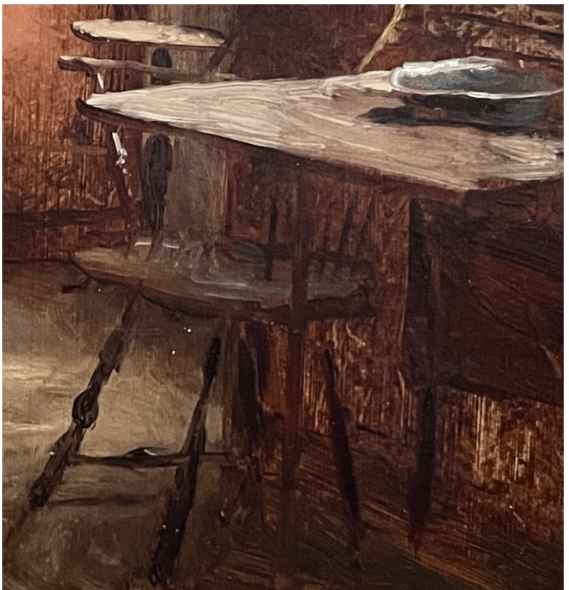

DETAIL, Eastman Johnson, The Other Side of Susan Ray’s Kitchen, oil on panel, showing Johnson’s expressive paint-handling on the rougher of the two tables.

A nice point of technique: Johnson painted the Chippendale with careful, smoothed-out strokes, but as you can see above, he used loose, rougher strokes for the table with the battered pan.

In the fancier Chippendale, the legs are neatly poised on the floor – there’s even a highlight on one of them, suggesting the piece hasn’t, after all, lost all its former glory. In contrast, Johnson let the legs on the simpler one more or less smear into the floor. For whatever reason, he definitely wanted us to perceive contrasting differences between the two.

It all combines to beautiful effect. Eastman’s uniformly rough, expressive lines, harmonized by his color choices and suggestive composition, give us the sense of a person, and maybe a nation, able to withstand volatile and trying times yet emerge determined to meet the new day ahead.

The tradition of genre painting features an appreciation of ordinariness, often with a certain nostalgia for a time and place now gone save in cultural memory. If you’re interested in trying your hand at this tradition, there’s a video by Sylvia Trybeck that takes you through the process of painting a tavern maid.