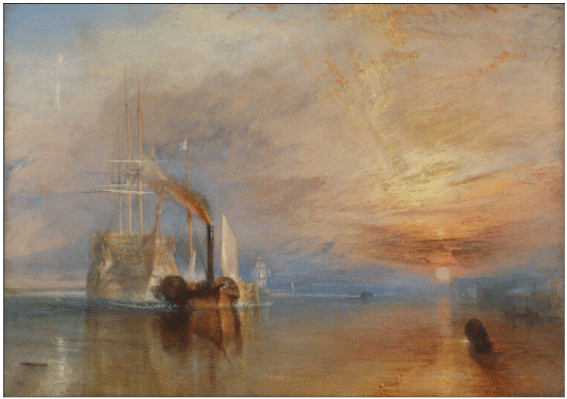

It’s “England’s favorite painting” according to a BBC poll in 2005, it’s reproduced on the British £20 banknote, and it’s one of the greatest paintings of the 19th century period. JMW Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire depicts a formerly glorious jewel of the British Royal Navy being towed to “her last berth” to be broken up for scrap after 40 years of service.

Although historically it was already de-masted and stripped of all its ornamentation, cannons, anchors and assorted hardware, in Turner’s painting the still majestic warship shimmers in and out of existence, decked in all her glory, an ornate silvery ghost. What’s going on here?

“It is unlikely that Turner witnessed the ship being towed,” says Britain’s National Gallery, which owns the painting as part of the Turner Bequest, the vast bulk of the artist’s work, donated to the nation upon his death. “Instead, he imaginatively recreated the scene using contemporary reports. Set against a blazing sunset, the last voyage of the Temeraire takes on a greater symbolic meaning, as the age of sail gives way to the age of steam.”

Clearly this is more than a painting of a boat. In fact, many of Turner’s paintings engage with political and social events, including arguably the core issue of his time and ours – the erasure of the Old World’s agrarian, pastoral relationship with nature to make way for the coming of the modern industrial and now technological age. That’s just part of how Turner saw and painted – he recognized and drew from what was happening to his world when he painted the things of his own time and country.

Similarly, Turner’s tendency to dissolve material things (even big ones like warships and castles) into shimmering light reflects a personal and richly imagined interpretation of Romanticism, the signature intellectual trend of the time in poetry, fiction, and literature.

How Did He Do It?

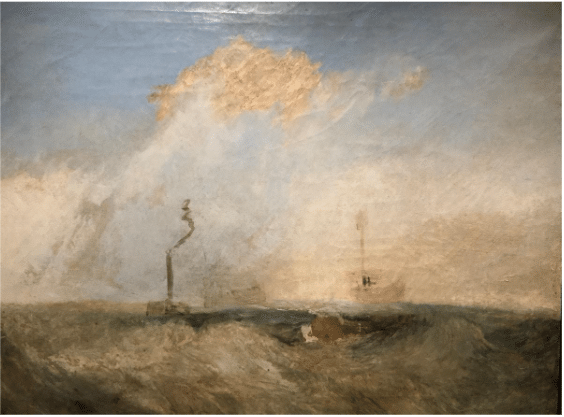

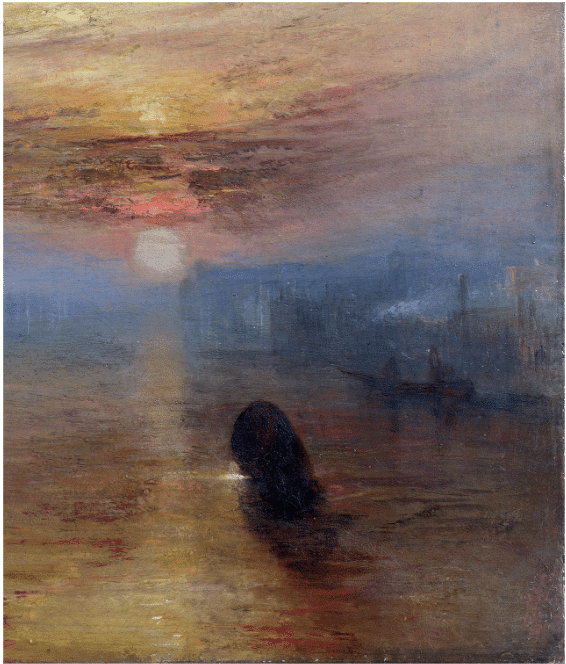

JMW Turner, Steamer and Lightship, Study for “The Fighting Termeraire,” oil on canvas, 1839. Exhibited in at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

Comparing Turner’s little-known initial sketch to the final painting yields insight not only into how to “read” a painting but into how great artists think and create the kind of painting that embodies meaningful experience.

Generally, Turner’s practice was to sketch on location in watercolor and pencil in tiny pocket notebooks. The current scholarly view is that it cannot be determined whether Turner actually witnessed the towing of the Temeraire, although several older accounts say that he watched the event from a variety of places on the river.

The truth is that it doesn’t matter. Turner worked out his initial idea as a small oil painting that already took liberties with the facts. In reality, it would have taken two steamers, not one, to move the warship’s battered hulk up the Thames. All that the canvas says on the back is that it’s a “first sketch” for The Fighting Temeraire.

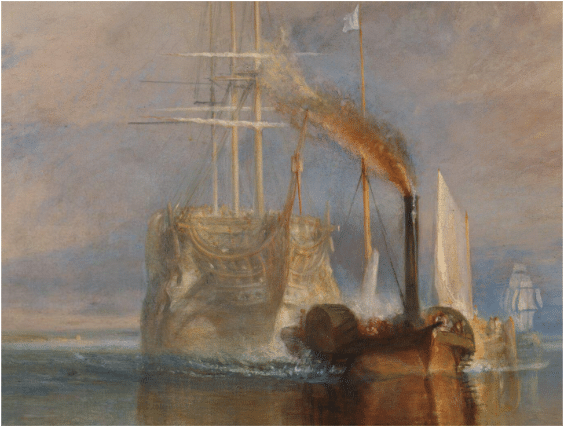

Detail of the painting. Behind the Temeraire (where the moon is rising) the water is blue green and the riverbank is green, but in front the water is iron-red and the riverbank is clogged with London’s urban architecture (see below). Turner moved the flagpole from the front of the tug to the back, behind its smokestack, presumably to make a stronger connection between the old tall ship and the white flag of surrender flying before it.

The final work, however, differs so significantly from the sketch that it’s clear the painting “happened” not from observation nor from the sketch, but from Turner. The sketch itself is less an accurate compositional study for a larger painting than a placeholder for an idea for a painting born in the collision between an event in the world and an artist’s sensitive, responsive mind. No doubt it was the significance and history of the Temeraire that sparked it.

The fact of the Temeraire’s towing was the seed Turner needed that day to fall on the fertile ground of his creative imagination. To be an artist is to develop the skills needed for expression while living open to inspiration at all times – to recognize and act upon your ideas when they come.

Britons celebrated the Temeraire as the hero of the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, the defeat of Napoleon, which secured imperial naval dominance for England on the world stage. By the late 1830s, however, the Temeraire was no longer relevant. Turner realized that its scrapping signaled the end of an entire historical period being eclipsed during his lifetime by technological changes affecting daily life more profoundly than any battle.

Turner’s “first study” (left) for The Fighting Temeraire nest to the final work.

Looking at the sketch, the basic idea and primary players are there: the steam-driven paddleboat, the ghost-ship behind it (barely visible, literally fading away), even the basic placement of the horizon line and the steamship left of center. But in the sketch the sea is choppy (without hinting at the final work’s mirror-calm, so much better befitting the moment). Nowhere to be seen is the final work’s low, setting sun, or the way its reflection in the water continues the steamship’s color like a stain.

Finally, in the sketch, the Temeraire sits to the right and behind the steamer, and both are about the same size; in the final work, the Grande Dame appears, majestic and significantly larger than the (darkened) steamer, in what has become a solemn procession beneath a classical arch of sky and clouds.

Detail, lower right corner of The Fighting Temeraire. What is that dark shape? In the opinion of Quora author Paul Zink: “From the shape, and the fact that the dark semi-rectangular object is attached to a larger object that is underwater, I’d say it’s the rudder of a scuttled, wrecked or sunken boat whose upturned hull can be seen just under the surface. You can see where Turner painted the ripples of the river water around the rudder sticking above the surface. The forlorn rudder is foretelling of the imminent fate of the once-proud HMS Temeraire.”

These differences are what suggest that The Fighting Temeraire began as an inspiration, a flash of insight, a vague idea – not a blueprint or even a distinct vision of the final work-to-be. Turner sketched a study that only told half the story. Later, drawing upon the study perhaps but in no way tied down by it, he revisited his initial impulse and evolved the painting into a far more meaningful whole. In that process, he created a mood corresponding to his inspiration with a newly invented composition and imagined elements ideally suited to convey the full force of the idea.

Contrasted with the sooty, black-chimneyed steamer towing it to its end as the sun goes down, Turner’s Temeraire resonates with symbolism: its sails furled, the ship is a mournful yet majestic stand-in for the history and traditions being lost as the sun sets on one age and the new age of global industrialization takes over. The steamboat is dirty, the Temeraire is magical, the mood is melancholy and contemplative, the sea calm and reflective as glass.

Detail of the London skyline from The Fighting Temeraire. On the left of the painting (below), being left behind, the old world’s green, uncrowded shores; here, on the right and straight ahead, the smoky industrial city.

Detail of the left side, showing the other bank of the Thames (?). If you didn’t know better, you’d never know this was the same river at the same time of day. It’s one more subtle bit of symbolism Turner has snuck into this painting.

My takeaway: Recognize the value of your experiences and use them to guide your creative endeavors. Your experiences are the seeds of your best and truest work.

Don’t discount your ideas just because they are yours or because you can’t remember anyone else making a similar painting you could use as a model. I think a lot of the time we don’t act on our ideas for a painting because we fear we won’t be able to pull it off. As Turner’s process makes clear, we are probably right! We won’t be able to pull it off – at least not on the first try.

And yet, and this is the difference between people who become artists and those who give up too soon: It’s making that first, embarrassing, discouraging, failed attempt ANYWAY that gets you to the next plateau, the one that eventually leads to the successful painting.

A contemporary painter of ships and the sea influenced by Turner, John Stobart traces his fascination for the subject to a visit to Liverpool at the age of eight. Following four years of training in drawing and painting as a young man at Derby College of Art, he continued his studies at London’s Royal Academy, where he was influenced by Constable as well as by Turner. In this teaching video, Stobart details his techniques when painting en plein air.