Terre verte, or green earth, as it translates, is a muted, transparent and relatively weak-pigmenting tint that’s been used for centuries.

As a clay mineral – celadonite and glauconite to be specific – terre verte is found in abundance near Verona in Italy and on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus, which is why it was used in wall frescoes by Roman artists in classical times.

Terre verte is a soft green hue that can range from pale bluish- to yellow-green. Its most famous source was an area outside the Italian city of Verona (setting for Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet), where it was mined until 1940, giving rise to its secondary name “Verona green.”

During the early Italian Renaissance, religious fresco painting used “green earth” in their underpaintings as a base color for the warmer skin tones which they painted on top. Fresco painters such Cimabue, Giotto, Masaccio, Fra Angelico, Correggio and Cennino Cennini borrowed the idea of a greenish underpainting from Byzantine artists (who kept Roman traditions alive for another 1,000 years after the fall of Rome, roughly 450 – 1450 AD).

Michelangelo (1475-1564), The Virgin and Child with Saint John and Angels (‘The Manchester Madonna’) (c 1497), tempera on wood, 104.5 x 77 cm, The National Gallery (Bought, 1870), London. Courtesy of and © The National Gallery, London.

Michelangelo’s unfinished The Virgin and Child with Saint John and Angels, popularly known as The Manchester Madonna, from about 1497, shows how an underpainting of Green Earths, visible at the left, was used to achieve realistic flesh tones. Later, painters came to prefer verdigris for this, but Green Earths worked particularly well in egg tempera, as in this case.

The green hue makes the flesh appear more life-like by adding cool halftones, tempering the warm tones of red and yellow ochre.

I’ve had this tube of Old Holland terre verte rattling around in various paint boxes of mine for years.

In short, the terre verte kept saints’ skin looking more natural because the artist could paint a thin layer (known as an “opaque glaze”) of pinkish white paint over top of it, allowing the green to show through and tone down the pink.

The Maesta by Duccio is in the Cathedral of Sienna, and it’s the most important painting in that city. Painted in the 1300s, Duccio shows us the Virgin Mary in majesty surrounded by angels and saints. As the more dominant of the two largest independent central Italian city-states, Sienna believed it had defeated Florence in 1260 by the grace of the Virgin. Sienna commissioned its greatest painter to create the large altar piece for the central, sacred place of honor under the dome of the cathedral.

Duccio’s green earth underpainting has become clearly visible as the red has faded from his figures’ flesh tones.

Unfortunately, earth pigments such as terre verte were among the most permanent, while transparent red pigments were among the least. That’s because, unlike the mineral earths, the reds came exclusively from organic sources such as plants and animals, such as cochineal beetles, which decay. The pigments made from them have long dried out and faded, revealing the green underpaintings beneath.

(It used to be said that the constant dusting of such paintings is what led to the pinker flesh tones wearing away and leaving the green faces. Not true, but how nice to imagine many years of Italian nuns or church deacons adoringly caressing the sacred figures in the paintings with a dust rag.)

Most terre verte is now a combination of natural earths and synthetic pigments (and luckily, reds are synthetic and way more permanent now). If you’re painting figures, you might want to try it. I don’t recommend it for foliage or foregrounds because it’s so weak. However, a plein air painter friend of mine calls it a lifesaver – “covers a multitude of sins,” he says – so perhaps you’ll find a use for it in your paintbox after all, even if you aren’t painting seasick saints and Madonnas.

Juliette Aristides “Touch”, oil on linen, 18.5 x 26.5

Any artist can improve their work by learning the “secrets” of the masters (so-called, because while they aren’t really secrets, few people are dedicated or passionate enough about their craft to absorb them). Check out these videos by master traditionalist Juliette Aristides for a deep dive into the “lost art” of the classical technique — a technique that captures purity and deep emotion no other can.

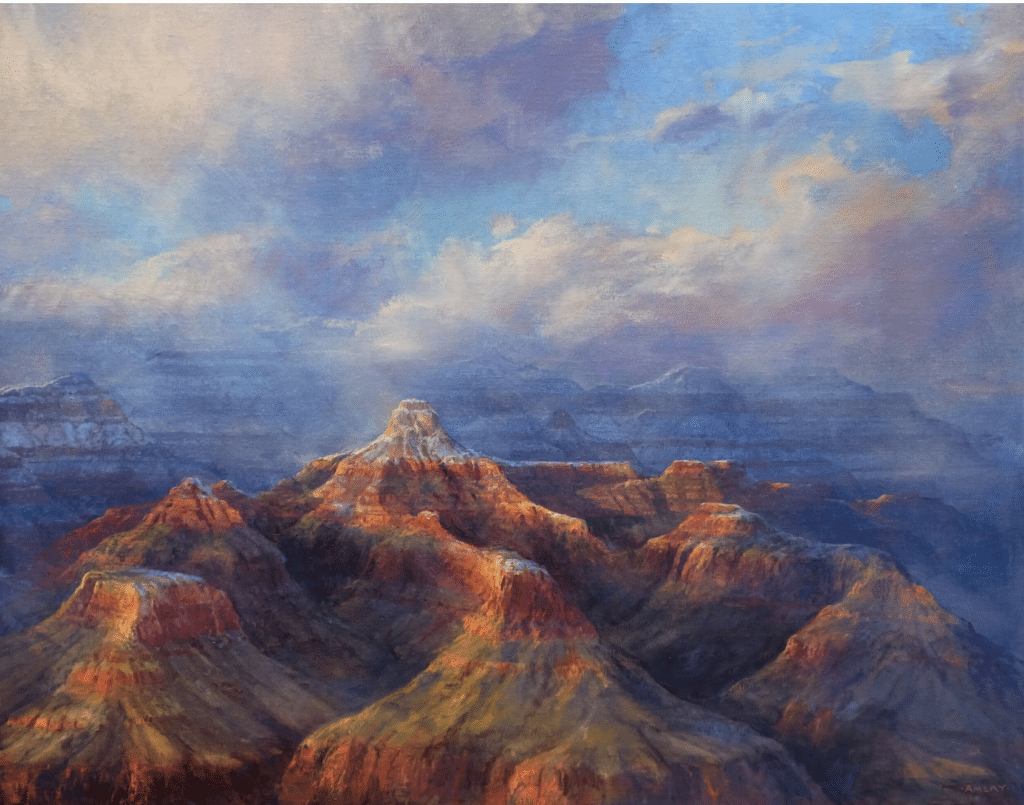

Romance of the Canyon

Amery Bohling’s “Love Letter to the West”

Amery Bohling, Romance of the Canyon, 33 X 48

Artist Amery Bohling is well known for her vivid depictions of the American West; she sees her entire body of work as something of a “love letter to the West.” Her light-infused work ranges from the seascapes of Cabo San Lucas to the granite cliffs and waterfalls of Monterey Bay, California. Her favorite subject, however — and the one for which she is most famous — is the Grand Canyon.

THE Canyon is “endlessly fascinating”, she says, “for its vastness, complexity, and transcendent light.” Bohling has painted the Canyon many times, finding challenges in capturing the timelessness of the rocks, the ephemeral quality of the light and sky, and the fiery reds and brilliant blues that dominate that unique landscape.

If you’d like to learn her acclaimed landscape techniques by painting your own version of this quintessential icon of the American landscape, check out Bohling’s video, How to Paint the Grand Canyon.