Witches abound in visual art, and one of the most striking images has to be Francisco Goya’s Witches Sabbath. Goya loved painting the fantastic and the grotesque; here he mirrors back the period’s fearful idea of what a ceremonial meeting of witches might look like.

Francisco de Goya, Witches Sabbath, 1797 (43 x 30 cm.)

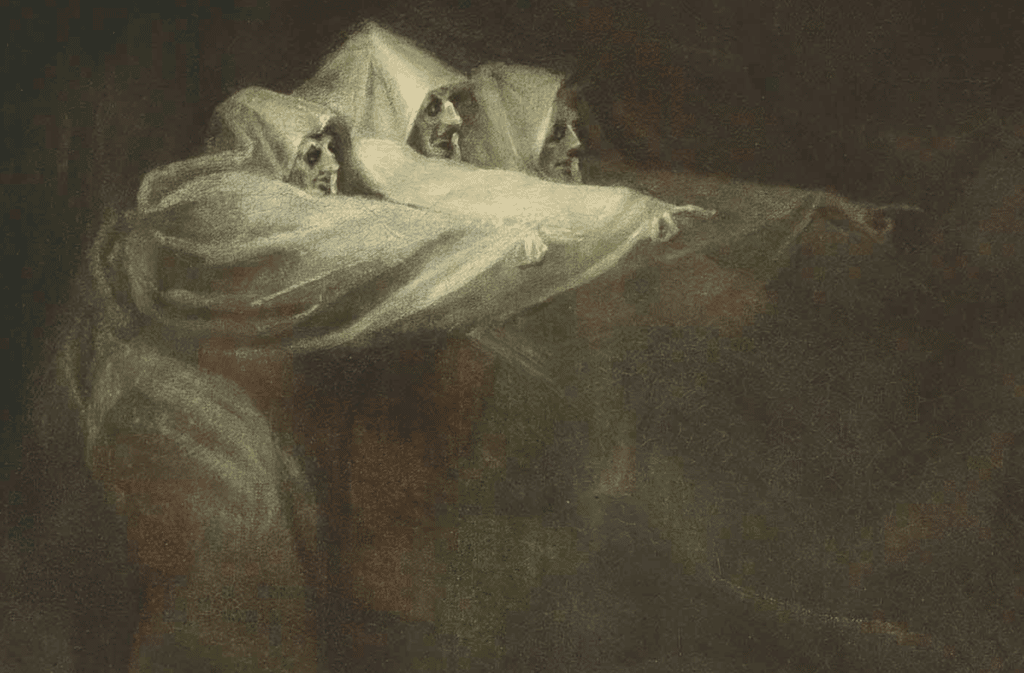

Likesie, Swiss-English artist Henry Fuseli’s (1741-1825) illustration of the three “Weird Sisters” from the beginning of Shakespeare’s Macbeth offers another image of supernatural eeriness from the period.

Henry Fuseli, Detail of the three witches from Macbeth and the Witches, c. 1820

More benign is John William Waterhouse’s (1849 – 1917) The Magic Circle. Here a sorceress draws a “circle of protection” around her steaming cauldron and the herbs she’ll soon be using to cast her spell. Ravens gather about (one, to the far left, perched on a skull) to watch whatever spooky action may be about to unfold.

John William Waterhouse, The Magic Circle, 1886, height: 182.9 cm (72 in); width: 127 cm (50 in)

Although its exact origins are obscure, the word witch is related to warlock and to wizard, the latter of which at least seems as if it ought to be related to wise. The old Anglo Saxon word wīglian meant to foretell the future. Rather than riding broomsticks or conducting dark “sabbaths” under a waning moon, in reality historical “witches” were more likely to be solitary “wise women” who, in fending for themselves on society’s fringes, had to know all kinds of folk cures and master the lore of the local plants, animals, trees, and herbs.

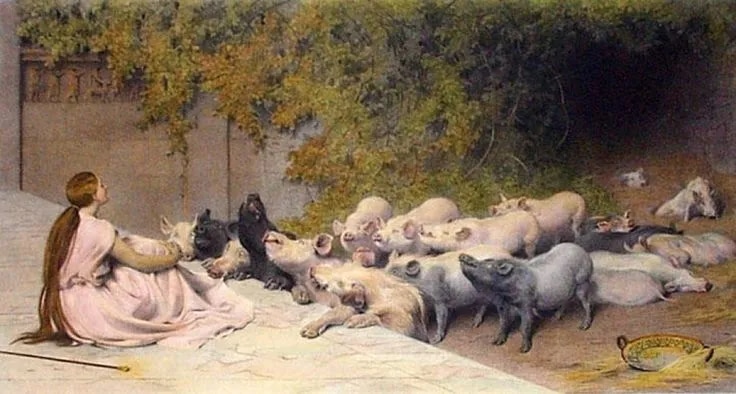

So the other side of witchery in art is female empowerment, though it often veered off to seemingly dangerous women whose power could not be “properly controlled.” One such figure is the witch Circe, who in Homer’s Odyssey turns Ulysses’ men into pigs. The Pre-Raphaelite painters painted this most ancient of witches several times in several guises.

Briton Riviere, Circe and Her Swine, 1896

Renowned in Greek mythology for her vast knowledge of potions and herbs, she wasn’t just a witch, she was an outright goddess of magic. She inhabited a garden palace amid dense woods on an isolated island. As Briton Riviere (Circe and Her Swine, 1896) paints her, she is placidly in command, a beautiful maiden enjoying the worshipful company of her herd of enchanted sailors, just like any country shepherdess with her flock (but not).

Earlier, John William Waterhouse painted her twice. In one painting, Jealous Circe, he depicted the witch-goddess as a smoldering seductress, poisoning water that will turn a love rival into a monster. Anthony Hobson describes this painting as “invested with an aura of menace, which has much to do with the powerful colour scheme of deep greens and blues [Waterhouse] employed so well.” Color is key.

John William Waterhouse, Jealous Circe, oil on canvas .(180.7 x 87.4 cm.) 1892

Waterhouse’s other Circe is more like the archetype of the Great Mother or Earth Goddess. This is at once a forceful and quite complex, not to say virtuosic, painting. Here Circe offers Ulysses a cup containing the same magic potion she used to turn his crew into swine.

John William Waterhouse, Circe Offering the Cup to Odysseus, oil on canvas. (148 x 92 cm.) 1891

You can see wily Odysseus’s reflection in the mirror behind Circe’s throne as she raises her wand, preparing to release her power. The cursed swine appear at her feet, behind the throne and reflected in the mirror, which also reflects, riding at anchor under a blue Mediterranean sky, Ulysses’ fabled ship.

May this season bring blue skies and maybe even a little magic – just the good kind! – into your creative life.

Magic in the Air – and on Your Palette

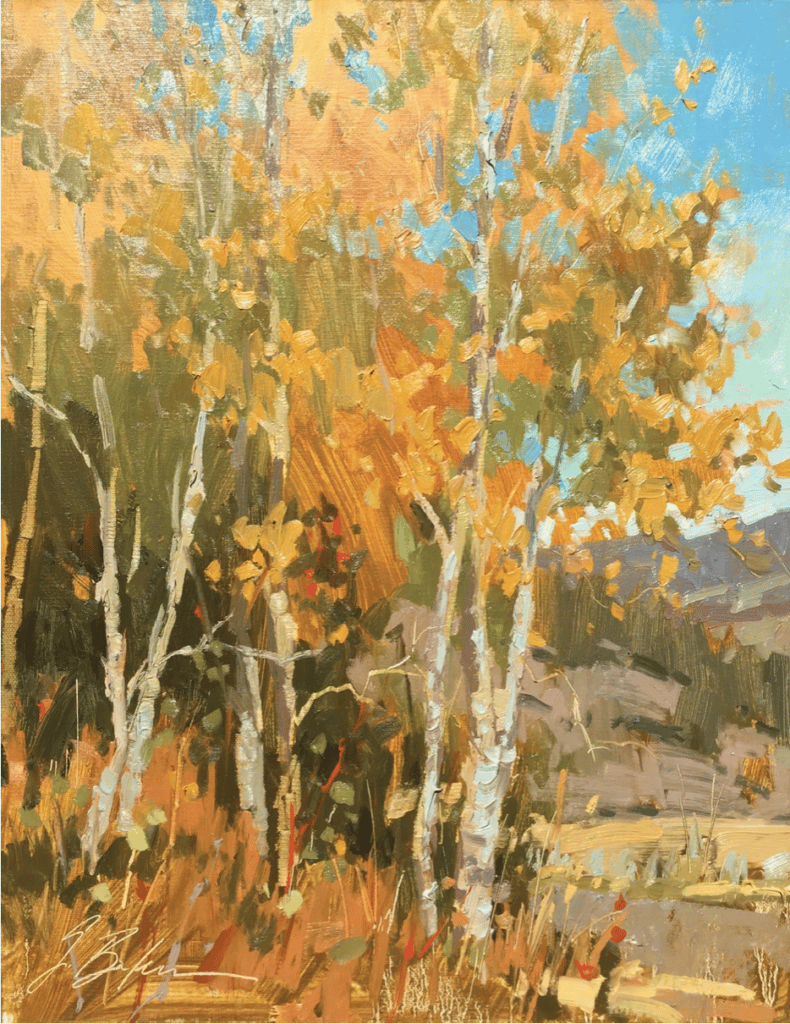

Suzie Baker, All that Glitters is Not Gold, 14″ x 11”, plein air oil on linen panel, 2019

Speaking of magic, there’s great instruction on using color effectively in Suzi Baker’s Color Magic for Stronger Paintings. It’s available from Streamline Publishing, and at a discount this month t0 boot.

In the paint,

Chris