Don’t believe the online art history buffs who say El Greco’s Toledo Landscape (finished in 1600) was the first cityscape. Not even close. Cityscapes have been a major subject in paintings since antiquity.

Ancient Rome

Roman wall painting from Stabiae, 1st century A.D.

Ancient Greece and Rome had a sophisticated, stylized tradition of representational painting that even boasted the rules of perspective (which the Middle Ages so shunned that the Renaissance had to re-invent the science nearly a thousand years later). Although most ancient Greek paintings were lost to time, we have descriptions of them in surviving literary works as well as copies in Roman frescoes mosaics, such as those preserved at Pompeii.

This painting is a fresco, which is the Italian word for “fresh,” as in “fresh paint.” In the fresco technique, an artist applies a layer of fresh plaster to the wall and paints right into it while it’s still wet. The result is a literal “wall painting” in which the work becomes a permanent part of the wall.

The cityscape above is from the ruins of an ancient luxury resort city about five miles from Pompeii. There’s real fidelity to life and perspective in the way the foreground tilts toward the viewer while the rest recedes. Columns and piers diminish diagonally and buildings become smaller and less distinct further back in the distance.

Dating to the 1st century AD, there’s nothing else like it in Western painting until basically the Renaissance, some 1,300 years later. By then, the Christian church dictated art’s subject matter, and cityscapes were on the “do not paint” list.

Late Medieval / Early Italian Renaissancehce

Ambrogio_Lorenzetti_-_Effects_of_Good_Government_in_the_city, c. 1338

The Italian Renaissance signaled a resurgence of interest in the ideals of classical humanism. In the 1300s, the city council of Sienna commissioned Ambrogio Lorenzetti (1290–1348) to create a series of frescos for the walls of the city’s municipal offices building in Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico. This mural was part of one of the first and most important secular cycles in the history of European art, a visual manifesto of the city’s commitment to enlightened civic government.

Compared to the Roman fresco, the work above titled “The Effects of Good Government in the City,” looks simultaneously more flat and more “3-D.” Prior to this time, the pious paintings of the Medieval era had acted more symbolically than realistically; prior to the Renaissance, fidelity to observation took a back seat to the illustration of religious principles.

The Lorenzetti cityscape sits on the hinge between these eras, when attention to realistic rendering was returning to Western art. As you can see from the odd angles of the rooftops behind vs. those in front, and the buildings on the left vs. the buildings on the right side of the painting, “scientific” perspective was still in development.

Northern Renaissance

Johannes Vermeer, View of Delft – 1660-1661 – Oil on canvas, The Hague, Mauritshuis

Johannes Vermeer, View of Delft – 1660-1661 – Oil on canvas, The Hague, Mauritshuis

Vermeer painted this realistic view of his hometown of Delft in 1660, when pure landscapes were still relatively rare in Europe painting. It’s been called “the most beautiful painting in the world,” and indeed Vermeer’s color and design make View of Delft unique. It’s arranged in a series of broad and irregular horizontal bands (sky, city, canal and foreground) like deep bass notes punctuated by the staccato assertions ofd numerous smaller verticals in the city spires and their reflections in the water, and the two prominent figures in the foreground. The graceful rhythmical divisions and subdivisions subtly unify the scene in an organic wholeness so natural looking we forget it was meticulously composed by the one of the greatest painters of the age.

French Impressionism

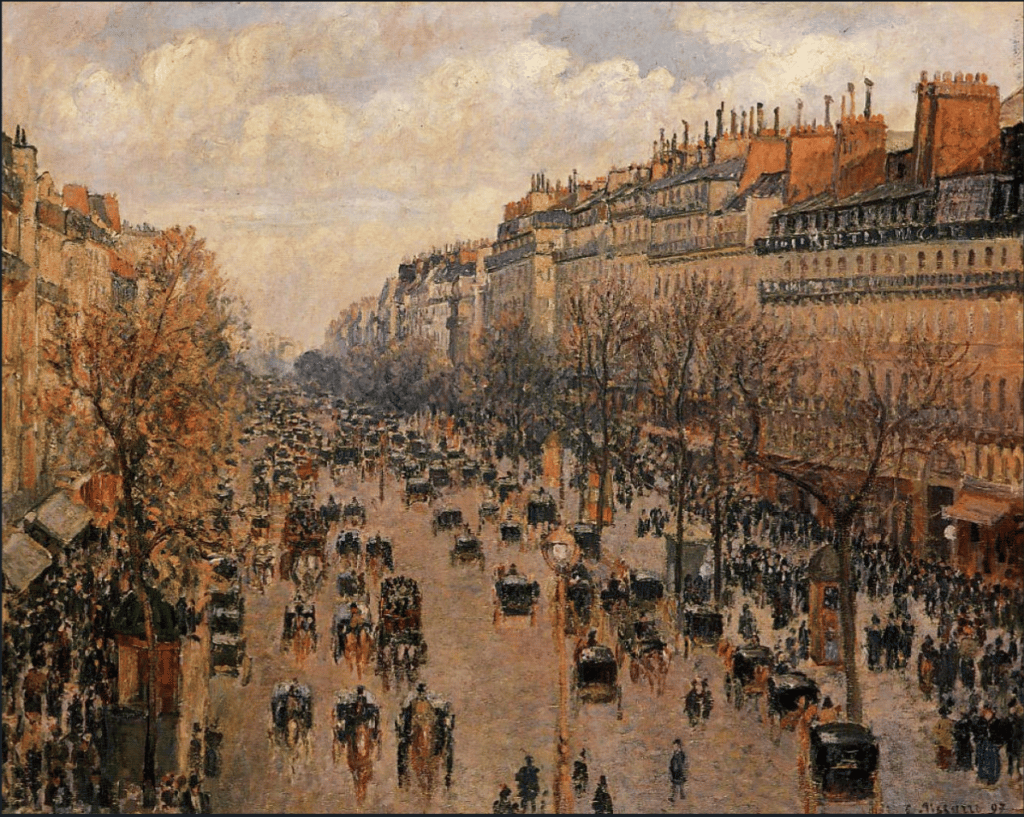

Camille Pissarro, Boulevard Montmartre, Spring, 1897

Any one of dozens of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings could qualify for this list, Monet’s flag-bedecked boulevards, Caillebotte, etc. etc. etc. Taking contemporary urban life as a subject was one of the major innovations of Impressionism in general. Pissarro’s Boulevard Montmartre, Spring and Boulevard Montmartre, Afternoon apply the Impressionist techniques of plein-air landscapes to the modern city on the cusp of the 20th century

Pissarro’s broad strokes of paint, carefully applied to the canvas, help convey the fragmented nature of modern life and his visual impression of the metropolis. These are two of a of 14-part series that painted in a room he rented for the purpose at the Hotel de Russie, overlooking the street. Following in Monet’ s footsteps, Pissarro depicted the same scene as it appeared during different parts of the day and different seasons of the year.

Camille Pissarro, Boulevard Montmartre, Afternoon, 1897

Contemporary Plein Air

Nancie King Mertz, “Light on Lake Street,” 2017, pastel, 16 x 12 in., Private collection, Plein air.

Nancie King Mertz is a Chicago artist working en plein air in pastels. She painted the intensely geometric Light on Lake Street in 2017. “I’m fascinated by Chicago’s “underbelly” — the structures and bridges that make our city unique,” she says. “I painted this piece during one of our PAPC Saturdays. The thundering noise of the “L” overhead encouraged me to finish in record time!

Nancy King Mertz in her element (photo from Arizona Pastel Artists Association).

In one of many instructional videos on painting the contemporary cityscape, Mertz details her process in a video titled Urban Pastel Painting.