Marcel Proust thought View of Delft by Vermeer “the most beautiful picture in the world.” It’s been called “a perfect painting,” and whether or not you agree, the artist’s picture of his hometown assuredly does repay close looking.

Is This Vermeer the Most Beautiful Painting in the World?

Proust wrote to a friend about the first time he saw it:

“Ever since I saw the View of Delft in the museum in The Hague, I have known that I had seen the most beautiful painting in the world.”

That day, on the way to the museum he’d swooned with a sudden feeling of weakness (shortly after, he took to his bed for the few remaining years of his life). He wrote the experience into his novel Remembrance of Things Past, in which his main character actually does die in front of the View of Delft.

Art writer Christopher Jones points to the way Vermeer handled the sky in this painting as perhaps its most spectacular aspect: “Those clouds are impeccably painted. See the way they diminish perfectly in size to create the sense of depth and space. See the way the light upon them falls with just enough variation so as to differentiate between each cloud formation, yet not too much so as to be impressive. It is such an ordinary sky — and that is why it is so perfect.”

Jones says that the higher, darker cloud (and I would say the same about the strip of foreground) “frames” the painting’s space in a way that invites us to see the painting as a painting, rather than a straight-up “view” of the city.

It’s said to be the kind of magical thing you could spend a lifetime dreaming over. Cityscapes at the time were relatively rare, and Vermeer painted three of Delft. In one of those other paintings, called Street Scene, Delft (the Little Street), Vermeer painted the bit of the neighborhood where he grew up.

Vermeer’s palette for all this, by the way, was super basic and primary: chemical analysis shows he used just madder lake, yellow ochre, ultramarine blue and lead white.

Johannes Vermeer, Street Scene, Delt (the Little Street)

It’s a small painting, about 20 inches (as are most of Vermeer’s works), but the detail is exquisite.

As relatively rare as pure cityscapes were at the time, no great painting emerges out of pure invention. Vermeer was building upon the solid foundations of the Dutch landscape tradition. We can check several boxes of standard features from Dutch landscapes in the View of Delft’s scale, its low horizon line, the overall color and luminosity, and the big shadowy-light cumulus clouds casting their shadow on the foreground waterfront while the middle ground area awash in sunlight peeps out behind. We looked at a landscape by Van Ruisdael recently that, just like the one below and like the Vermeer, employs:

- a low horizon line

- big sky with a mix of warmly lit and shadowed clouds

- diminutive figures and architecture that establish a sense of grand scale

Jacob van Ruisdael, An extensive landscape with grain fields, Heemstede beyond, c.1660–1670

None of this, of course, is arbitrary. Radiography shows that Vermeer deliberately extended the reflections on the right late in the process. These vertical lines connect the middle ground with the foreground and anchor the whole design. The reflections on the left and in the center also visually connect the bank with the line of architecture. To the left, they frame two small figures, (there are 15 in all).

In each detail, whether the sun-baked brick, the green masses of trees, the slightly blurred reflections, or the figures, Vermeer spotlights just the right essential details – and no more. Realists interested in the foundational principles of old master painters like Vermeer might be interested in Virgil Elliott’s video Traditional Oil Painting – the Principles of Visual Reality.

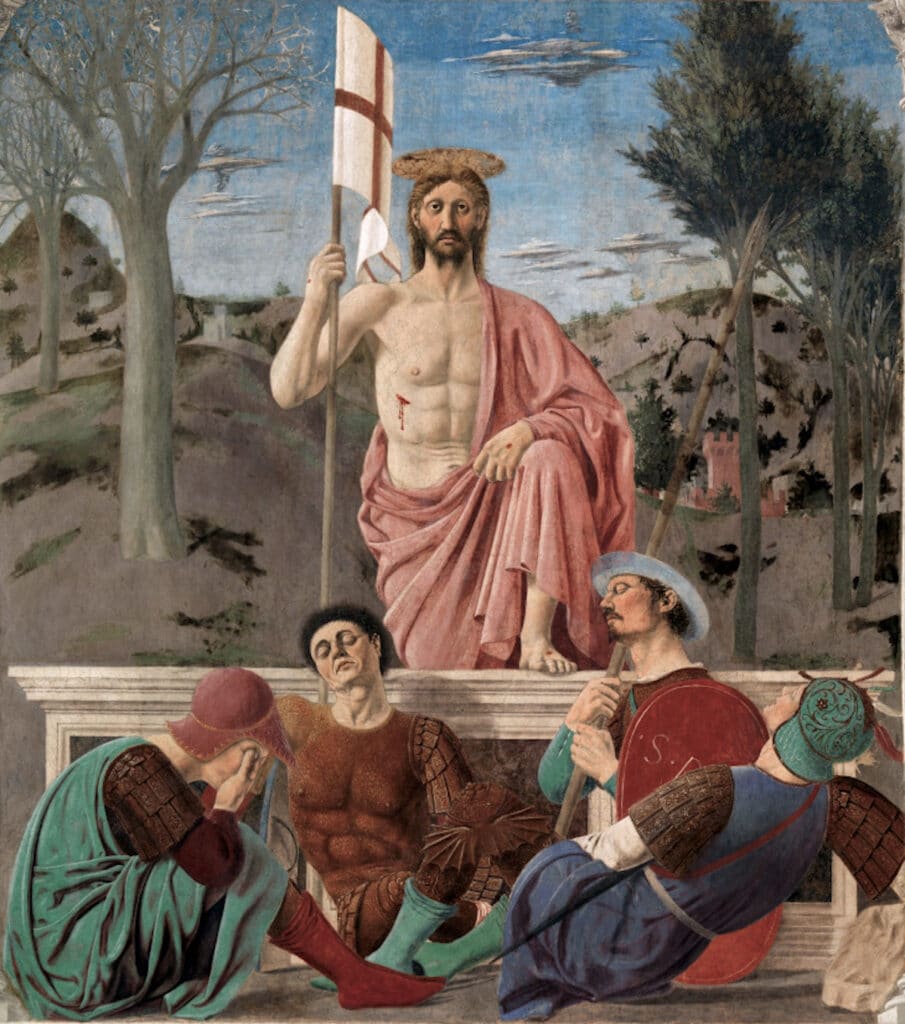

Contender No. 2 for “Best Picture” (and How it Saved a Whole Town)

Piero della Francesco, Resurrection of Christ, c. 1645