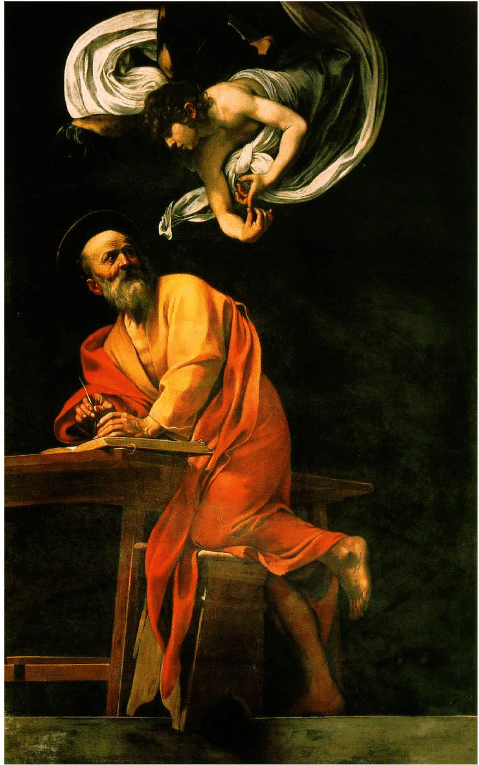

Caravaggio’s masterful “The Inspiration of Saint Matthew” remains a priceless treasure of European art. However, it wasn’t universally admired and almost didn’t get hung – or painted – at all.

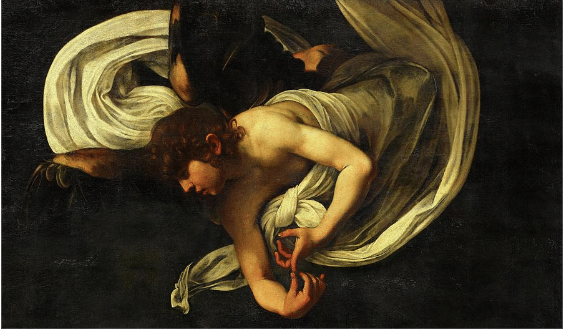

As you can see from the closeup above, this is a very fleshy, worldly (not otherworldly) angel; he’s clearly got skin and evidently blood, given his flushed ear, lips, and fingers. The artists used a street kid as a model. This is an angel the Roman Catholic church at the time would only have accepted with serious misgivings. The angel, by the way, is instructing Matthew what to write in his gospel (as the rest of the painting makes clear). To the church it was distasteful; to us, it’s a beautiful image.

Caravaggio, “The Inspiration of Saint Matthew,” oil on canvas, 292 cm × 186 cm (115 in × 73 in) 1602.

It was always a beautiful image, and it still is. What kept its first audience from seeing that? Call it “taste.” De gustibus non est disputandum goes the Latin maxim, often translated as “there’s no accounting for taste.” But taste is a funny thing. We say it’s subjective, but it’s more complicated than that, because massive currents of ideas, assumptions, histories and prejudices feed invisibly into whatever “subjectivity” really is. Beauty, however, remains.

Caravaggio’s “Inspiration of Saint Matthew” in its natural habitat (Italy).

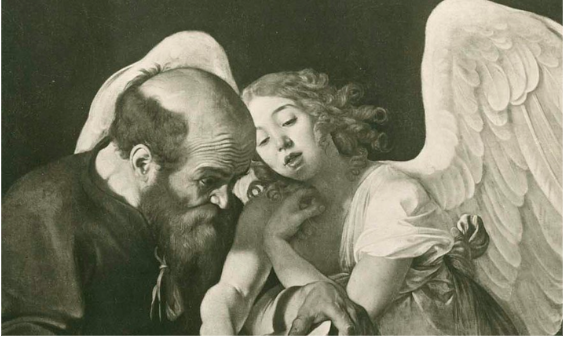

For Caravaggio, the painting was an irksome second attempt to satisfy a commission for a wealthy church’s altarpiece. The rejected first version (pictured below, and also obviously beautiful), was destroyed in World War II. In that version, the angel looked at least a bit more like a heavenly being, as we can see from black and white photographs that are all we have left of it. Still, even that angel’s swollen, feminine lips would certainly have been seen as “sensual” and therefore neither beautiful nor appropriate. But that same lost first version (below) also showed Saint Matthew as a poorly groomed old man with dirty feet, and that was definitely straying too far from the tastes of the day – nothing “beautiful’ about it.

It was all in keeping with Caravaggio’s maverick style, but the church leaders thought it too crude and decided they didn’t want a picture of someone they thought looked like a beggar hanging in the place of their sacred altarpiece.

Closeup of the first, now lost version of Caravaggio’s “St. Matthew and the Angel.”

They grudgingly accepted Caravaggio’s second, even “less holy” angel (top of the page). The replacement angel seems even more human – it’s clearly a portrait of a street kid Caravaggio paid to model for him. And Caravaggio did nothing this time to disguise the fact! Yet in both cases, the work’s beauty was and is plain to see, despite transgressions of accepted protocol, propriety and taste.

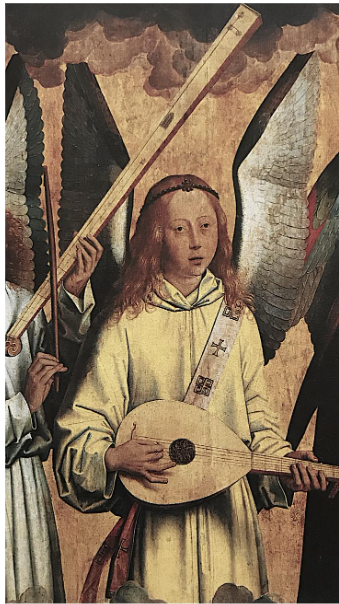

“The trouble about beauty is that tastes and standards of what is beautiful vary so much,” writes E.H Gombrich in his history text, “The Story of Art.” Gombrich cites two earlier religious paintings, both painted in the fifteenth century, both representing angels playing the lute, one of which is traditionally beautiful and one that is sort of … awkward – but beautiful anyway.

Melozzo da Forli, Angel, c. 1480

This (Melozzo’s Angel, above) is the first, more pleasing of the two. “Many will prefer the Italian work by Melozzo da Forli with its appealing grace and charm, to that of his northern contemporary Hans Memling,” he writes.

But, not so fast! Despite the first one being “beautiful” (and the other … what? Not? Less so?), it is certainly possible, Gombrich correctly points out, to like both equally.

In the case of the second, less obviously appealing painting (below),“it may take a little longer to discover the intrinsic beauty of Memling’s angel, but once we are no longer disturbed by his (the angel’s) faint awkwardness” – or biased toward unexamined preferences for prettiness – “we may find him infinitely lovable.”

Hans Memling, Angel, c. 1490

Have a look and see whether you agree. Gombrich is saying that, though at first glance Memling’s angel looks sort of stunned, just stiff and vacant-faced, once you give it a closer look and sit with it for a few and forget what angel-paintings are “supposed” to look like, you may begin to see something else – something sort of innocent, tender, unassuming, and “lovable” about him after all.

In pursuit of beauty, it’s important to look and look again, to see and to experience what’s actually there, going deeper than a glance and looking past the obvious. Gombrich demonstrates as much by showing that some things initially thought inappropriate or “awkward” can be discovered to be intrinsically beautiful if we meet them on their own terms.

So, is beauty not, as the cliché has it, in the eye of the beholder after all?

I’d answer, no, beauty is not in the eye of the beholder. The saying hints at a real truth, but there are at least two reasons “beauty is in the eye of the beholder” isn’t necessarily true:

- If everyone has a different idea of beauty, we would not set it as a goal in art, architecture, design or anything else, and

- All (or nearly all!) eyes do see beauty when it is truly there.

Sure, people are biased and know what they like and everyone is free to like or dislike whatever they want. Nonetheless, vast numbers of people do in fact agree that many actual things in this world are indeed beautiful – truly, self-evidently, heart-achingly, undeniably beautiful.

Therefore, beauty cannot *just* be purely a subjective thing, regardless of how often the “eye of the beholder” phrase is quoted, or where, or by whom. Otherwise, the tens of thousands, even millions of people who do in fact agree in no uncertain terms that certain things are beautiful wouldn’t be able to agree with each other at all.

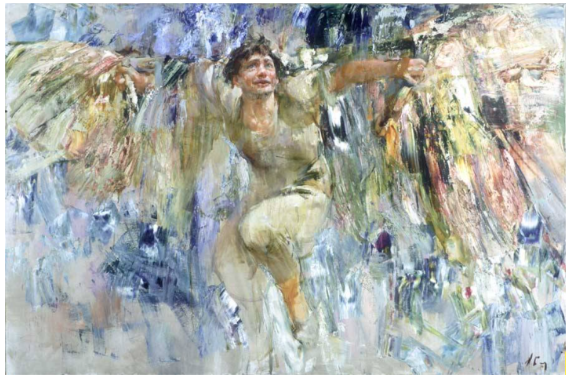

Nikolai Blohkin, “Icarus,” oil on canvas, 55 x 83 in.

It’s not well known, but the saying about the “eye of the beholder” did not come from some respected ancient philosopher. It was intended as a dig by an unreliable narrator in a dime-store romantic-comedy novel. We say it thinking it’s a self-evident truth, but resorting to the phrase in discussions about art is unproductive because it shuts down further discussion.

Making and seeing art teaches us that there’s more – a lot more, in fact – to learn about beauty, far more, certainly, than meets the eye.

Nikolai Blohkin, “Prior to Entrance,” oil, 37 x 46 in.

If you have an eye for the old masters, you can significantly improve your work with Nikolai Blokhin’s video Russian Master Portraits.