If you tend to feel stumped by trees and you’re ready to branch out … (okay, okay, sorry. Starting again..).

Trees can be an intimidating aspect of painting the landscape. However, it doesn’t have to be as complicated as you might think. For a quick tutorial, let’s look at mid-twentieth-century American landscapist Chauncey Ryder.

You won’t find Chauncy Foster Ryder (1868-1949) in the standard art history textbooks. He’s a landscape artist’s artist – meaning that it’s primarily painters (New England landscapists, anyway) who know and study his work. You can acquaint yourself completely with him here.

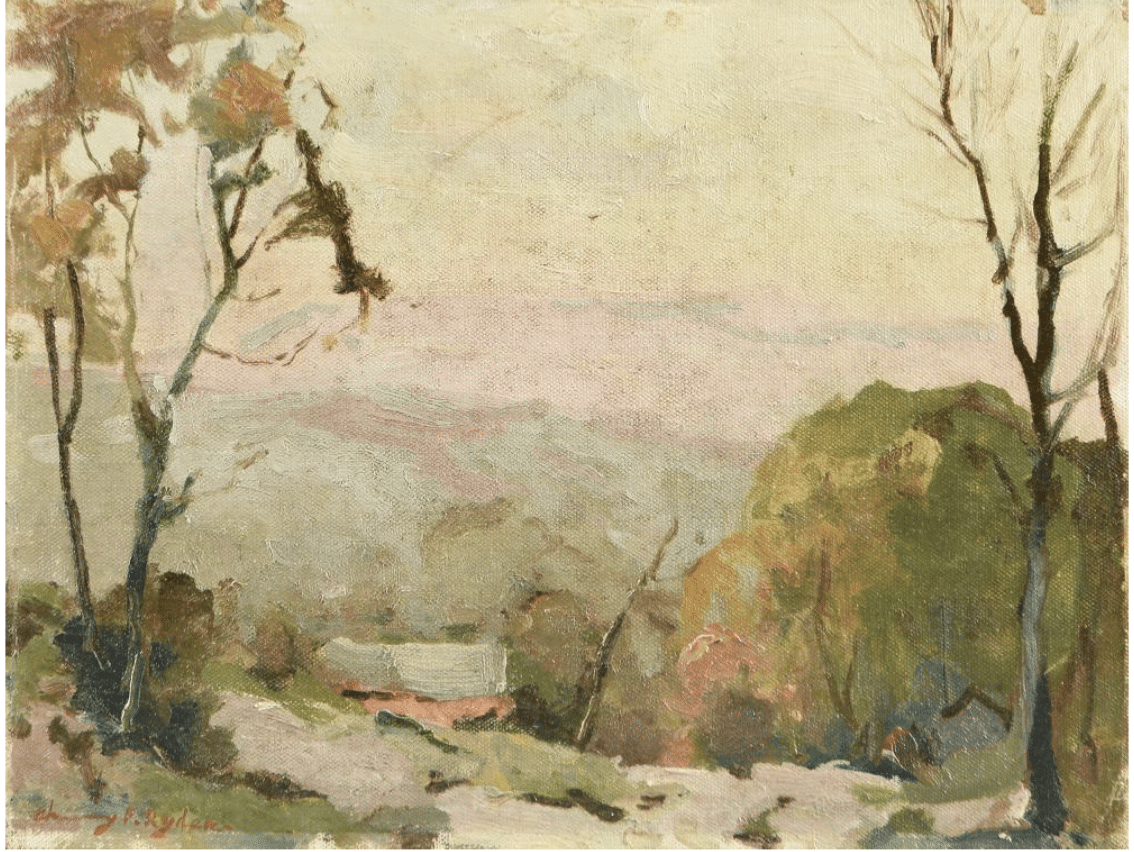

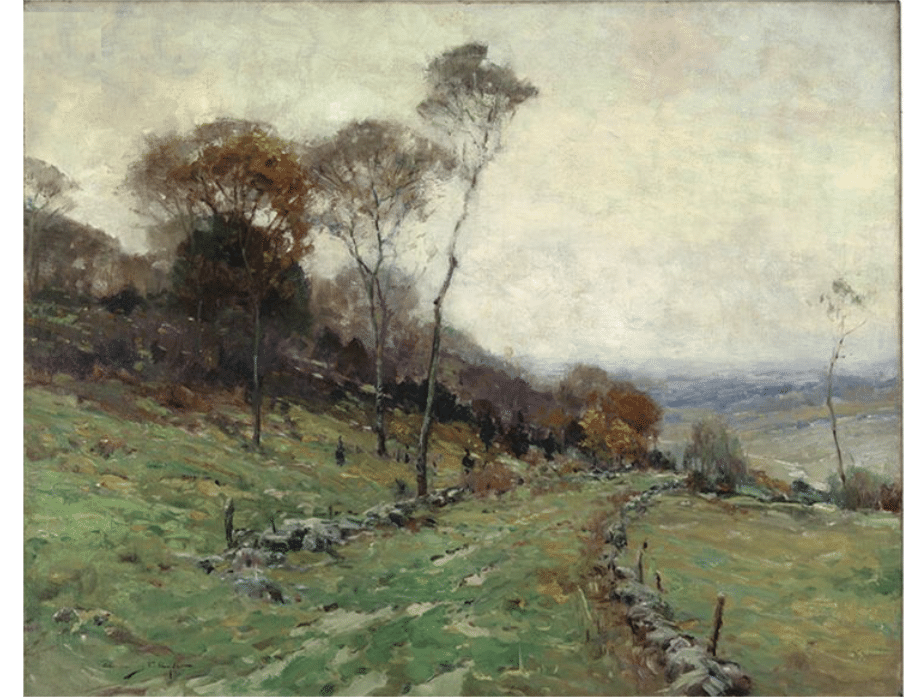

Chauncey Ryder, Autumn Hillside, oil, approx. 15 x 20 in.

Chauncey Ryder’s style corresponds to that of other pre-WWII, post-Impressionist landscape painters of New England who are better known yet still relatively obscure, such as John Enneking, Charles Hawthorne, and John F. Carlson. As one writer saw it in 1978, Ryder painted with intuitive feeling in pursuit of “the poetic aspect of nature.” His paintings are lively, loose, and convincing.

There is indeed a poetry to his work. What’s really striking about his landscapes and a little odd in a good way, has to do with his trees. There’s something he does that ensures we immediately recognize his landscapes by the “tell” of his trees.

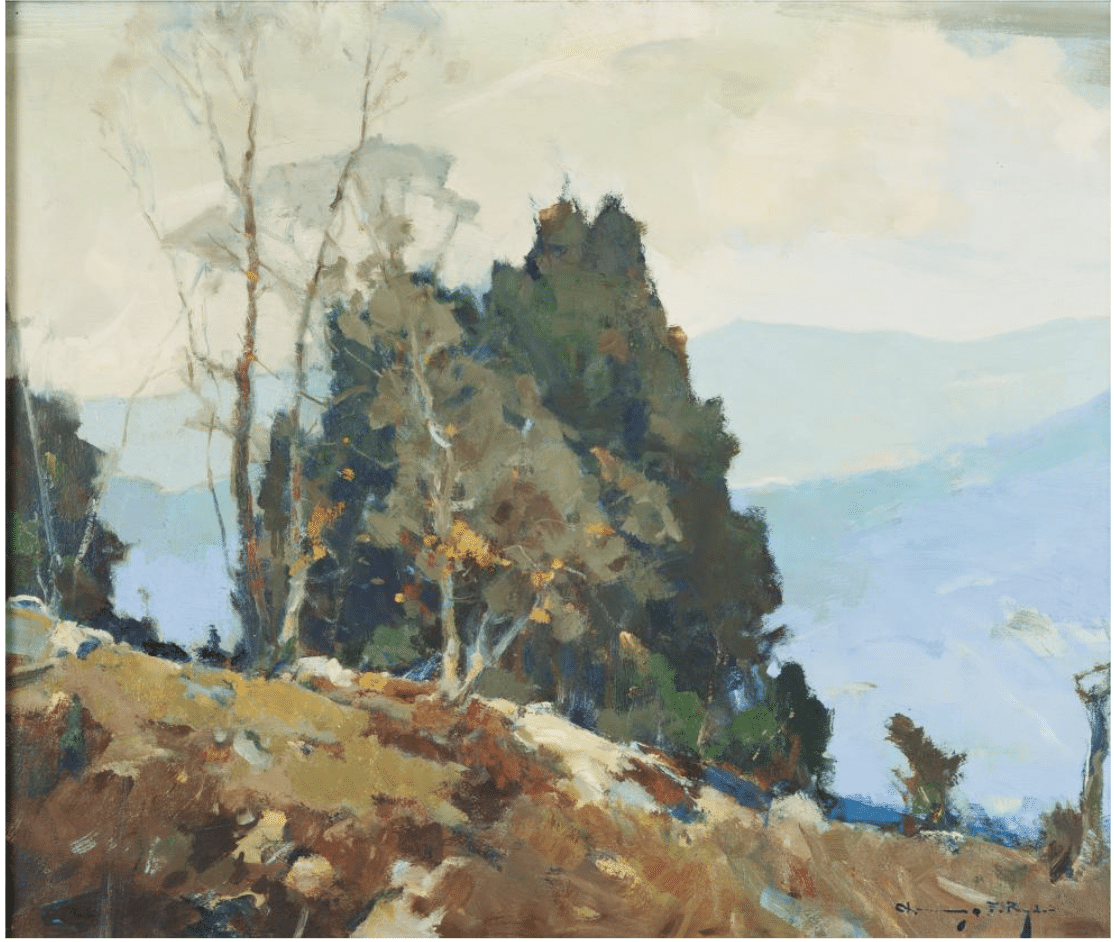

Chauncey Ryder, Village in the Valley, oil

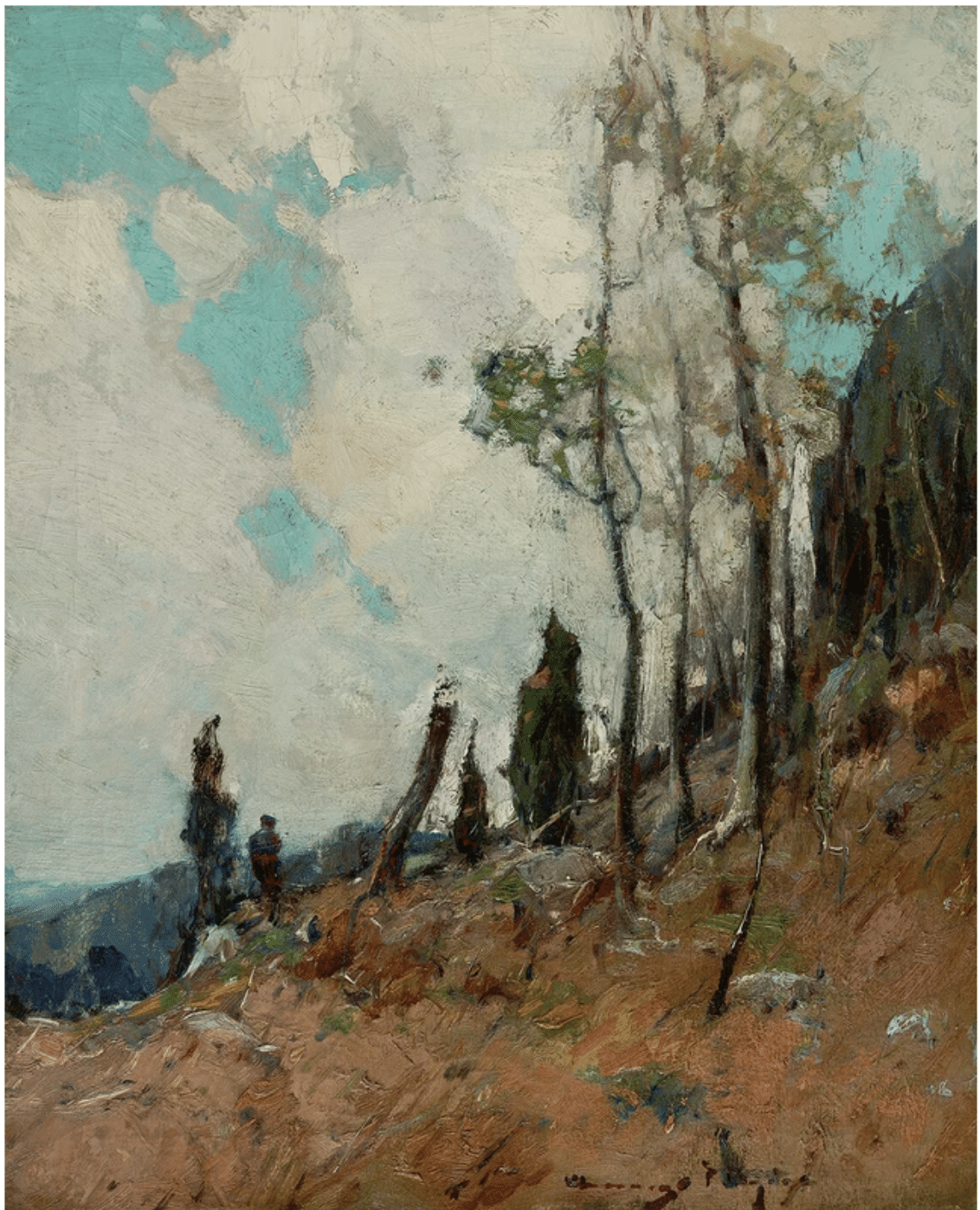

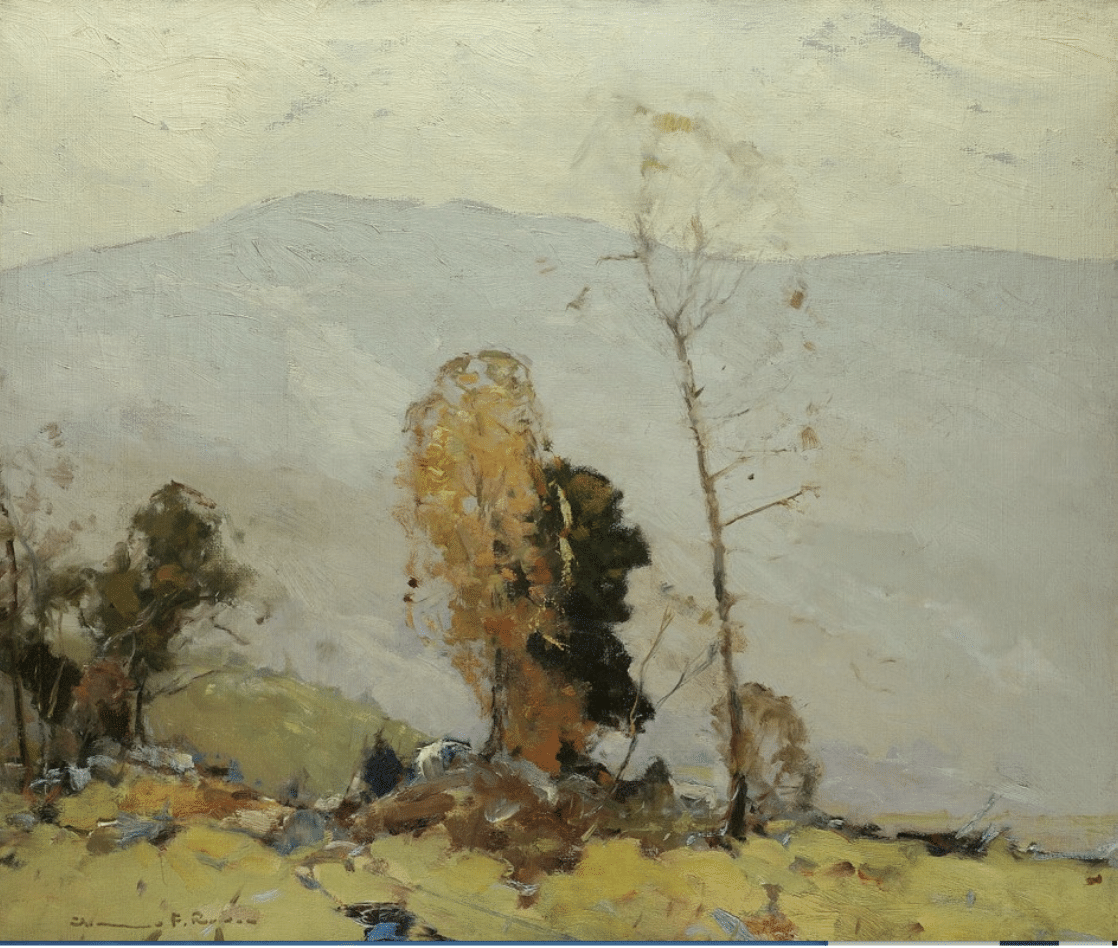

Chauncey Ryder, On the Mountainside, oil approx. 30 x 24 inches.

Do you see it? For one thing, Chauncey’s trees are tall – really tall. And thin. Not the clumps of hemlock or hardwoods that jut like lumps from his middle grounds – those are just supporting actors. The stars of the show are the spindly, jerky, brittle-looking trees with abbreviated foliage. Chauncey’s trademark skinny trees manage to be both elegant and awkward the wonderful way real trees can. They take root in the painting’s foreground and go on to dominate the composition.

There’s a wonderful sketchiness about them – and it corresponds to how we perceive them in nature when we’re not scrutinizing them and trying to figure out how to paint them. He does so much with so little; all he seems to do is put down a few smudges for leaves and connect them with a few rough, seemingly hastily drawn branches and trunks and voila – trees.

There’s a marvelous economy at work here! We can simplify the process (of the long, spindly looking trees, not pines or other full-leafed hardwoods) by thinking of the tree as having three main values – dark trunk, lighter branches, even lighter leaves. Despite his using a virtual shorthand, the end result is believable (and somehow charming!) trees. A close analysis reveals his technique, and it’s one you can apply to painting thin and branchy trees in general.

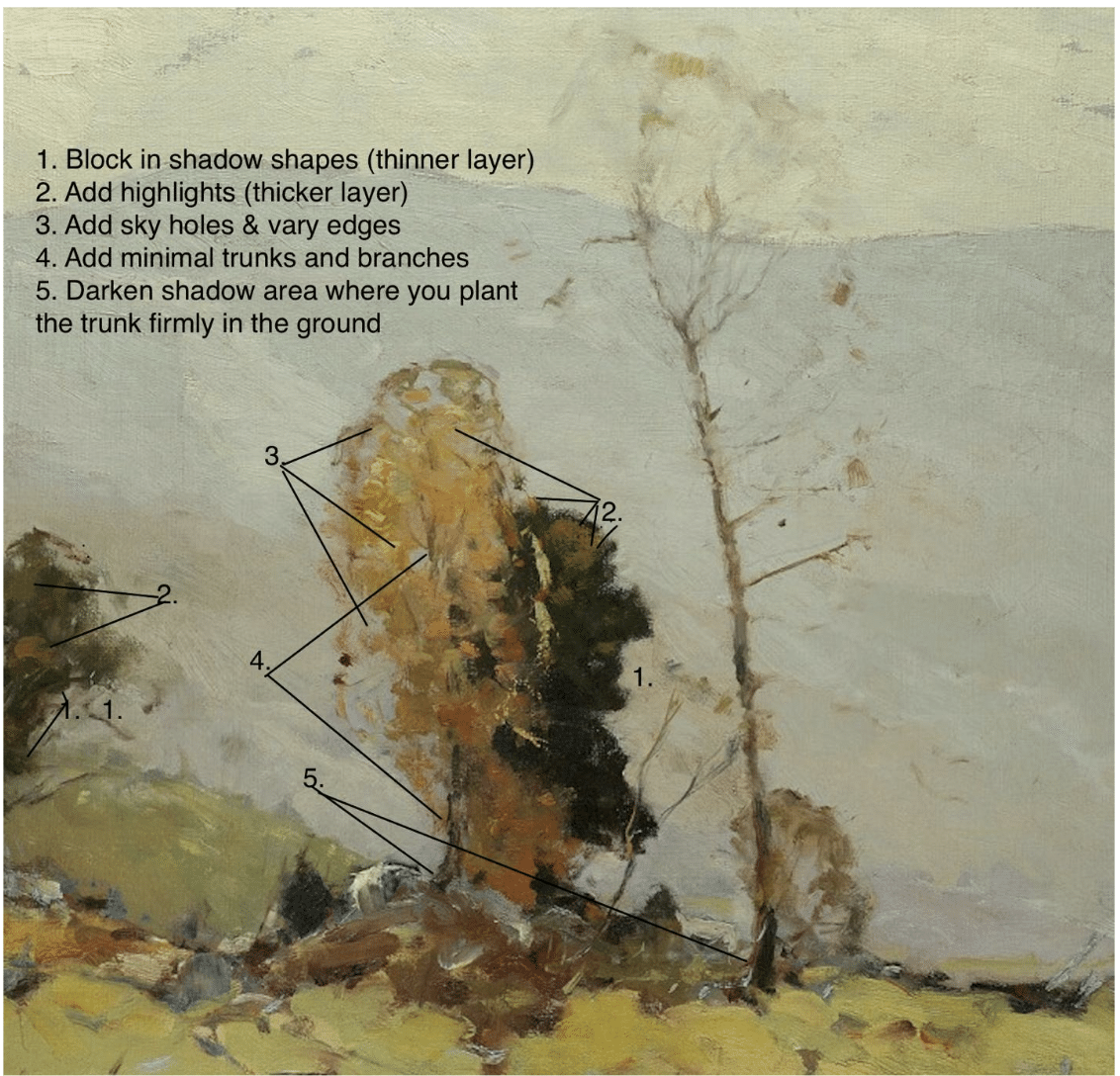

Chauncey Ryder landscape with signature spindly tree.

Let’s look at the landscape above. Here is the order I think he worked in:

- Block in the background sky with a thin layer of fairly dry paint (little to no medium).

- Begin the tree with the trunk firmly planted in the ground. This is usually (though not always) the darkest part of the entire tree; most times the rest of the trunk, and pretty much always the smaller branches, are rendered in a lighter value. At any rate, it’s good to start at the bottom and, holding the brush or knife like a pendulum, draw the trunk upward, deliberately bending and tilting the tree in segments (avoiding the temptation to make it ascend in a straight perpendicular line).

- Chauncey probably then mixed a very small bit of white with his trunk color to lighten the value and neutralize the color intensity in the higher parts of the tree, especially where he’d extend the branches outward, laying the paint down with a thin brush over the existing layer of thin dry sky color.

- Then come the minimalistic brush marks and smudges of a still lighter value for clumps of foliage, often positioned at the far end of the branches.

- Finally, he’d get more sky color on a small to medium-sized brush and redo the background and sky holes – painting over some of the foliage applied in the previous step as well as between the branches.

As far as the more conventional supporting actor trees, the standard procedure is diagramed below:

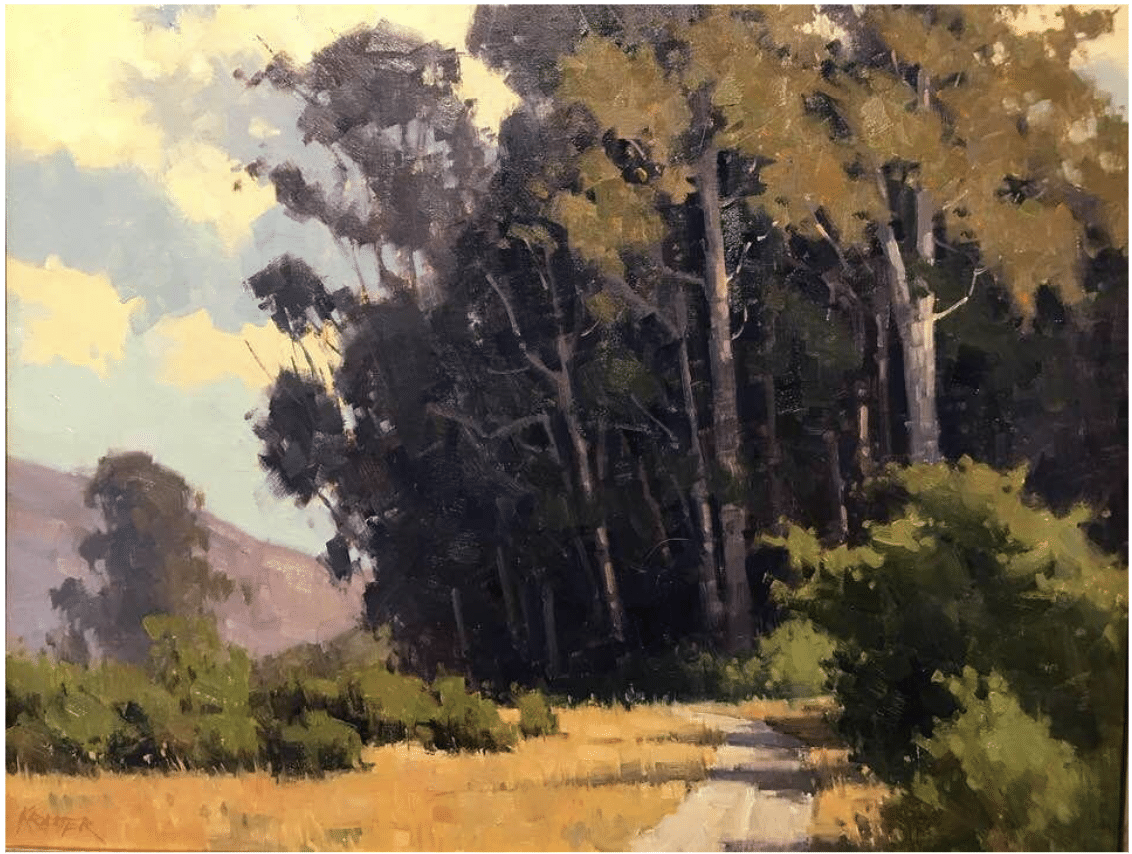

If you’re looking for a more methodical, in-depth tutorial on learning to paint the many-limbed one-legged ones, see if Paul Kratter’s video, Mastering Trees is for you.

Paul Kratter’s grove of trees in California demonstrates the importance of value in capturing trunks, foliage, and branches.

Looking for a great way to practice trees? Plunge right in at this May’s Plein Air Convention and Expo at Great Smoky Mountains National park.