“Form is never more than a revelation of content.” –Denise Levertov

The American poet Denise Levertov used the term “organic form” to describe how all the parts of a work of art relate to the world, the artist, and to each other. “There is a form in all things (and in our experience),” she wrote, “which the poet (or artist, writer, etc.) can discover and reveal.”

Levertov’s ideas can prove inspiring for artists working in landscape, portraiture, still life or any genre or combination of genres. One of art’s universal purposes, she’d say, is to embody the artist’s lived experience.

Lived experience is different from visual observation, but the two are strongly related (or at least relatable to each other). Painting, these ideas suggest, embodies a combination of our inner and outer worlds.

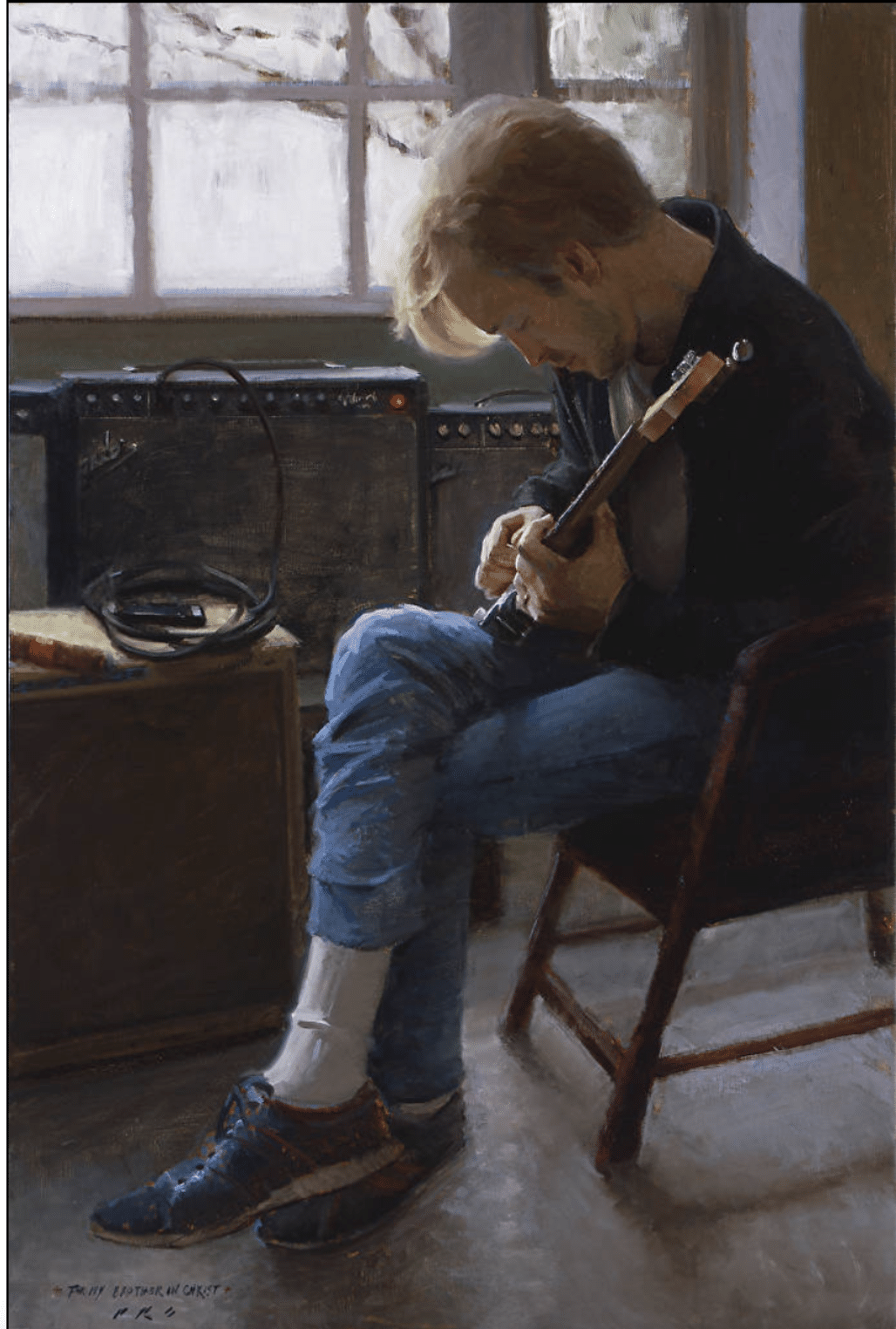

Charlie Hunter, “Arch Bridge, Bellows Falls, VT,” oil, 24 x 24 in.

There’s the landscape “out there” and there’s a corresponding “inscape,” she says, that blossoms alongside it within the mind and heart of the artist. If we call outside the horizontal axis and inside the vertical axis, the work of art takes shape somewhere near the intersection of the two.

Borrowing this concept from poetry and applying it to painting, the idea of painting as springing from the intersection of experience and observation can be liberating. It reminds us that within whatever framework or tradition we’re working, we always have the freedom and “latitude” to play, that is, to bring our own feelings and perceptions about the subject to the table.

Not all artistic approaches follow this route. Levertov notes that, “There are no doubt temperamental differences between poets who use prescribed forms and those who look for new ones.” Some painters revere tradition and prefer “a tight schedule to get anything done,” as she puts it, and others value experimentation and “want to have a free hand.” But in real-world terms, how deep do these differences go?

Perhaps we can answer that by way of another idea of Levertov’s, which is that form is a revelation of content. In other words, form (which includes medium, technique, composition, and all the “rules” of artmaking) can be more or less tweaked to reveal (or express) content, which comes from aspects of the artist’s lived experience.

That may sound dry and academic, but it’s huge!

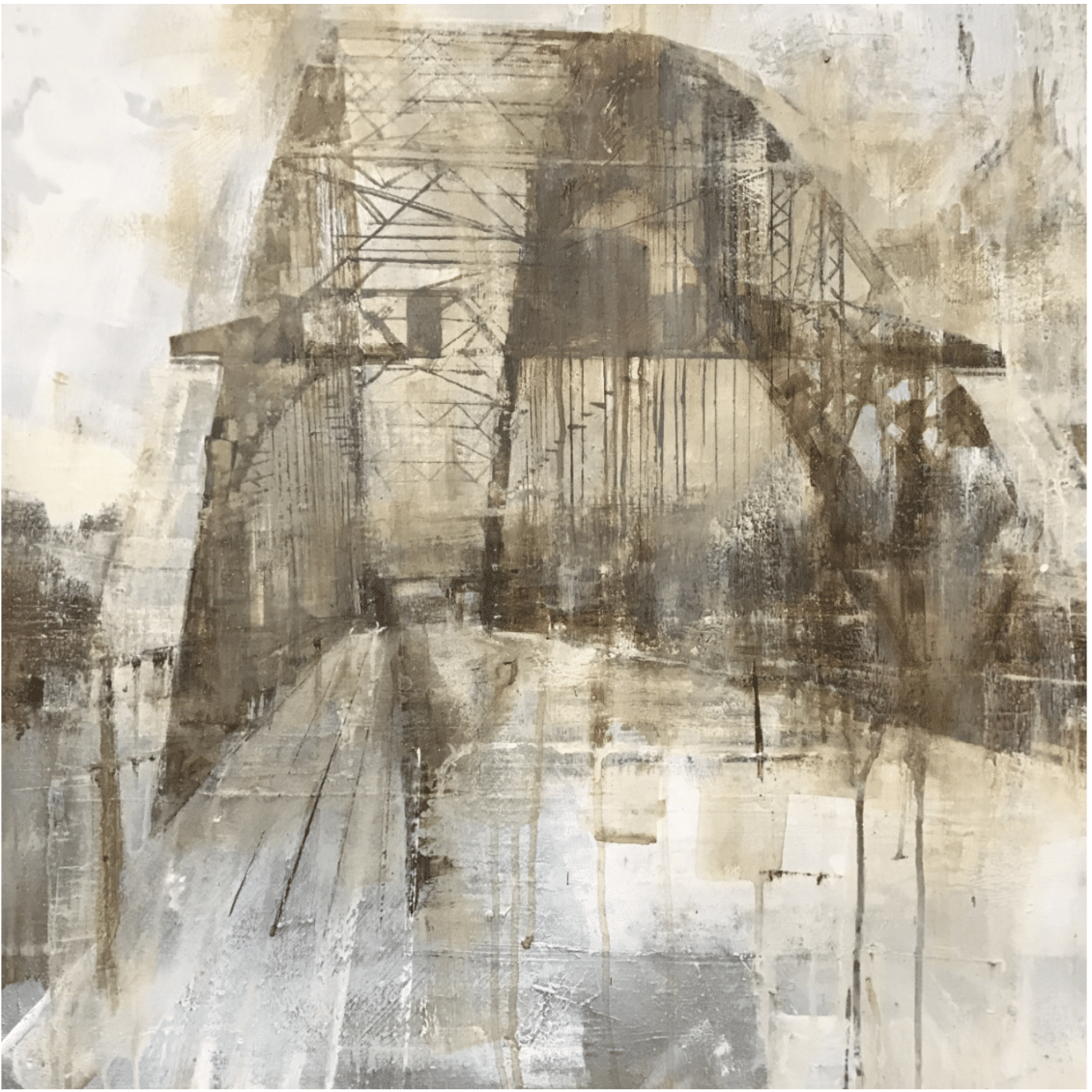

Charles Reid, still life with flowers, watercolor

“So,” she writes, “as the poet (or painter) stands open-mouthed in the temple of life … the pressure of demand and the meditation on its elements culminate in a moment of vision, of crystallization, in which some inkling of the correspondence between those elements occurs.”

During the creative process, Levertov says, various elements of the artist’s self are in communion, with the tradition, the visible world, and with each other.

Eye, intellect, and passion “interrelate more subtly than at other times; and the ‘checking for accuracy,’ for precision … that must take place throughout … is not a matter of one element supervising the others but of intuitive interaction between all the elements involved.”

The initial vision, though, remains important from beginning to end. “It is faithful attention to the experience from the first moment of crystallization,” she says, that allow the first strokes of a plein air painting, to stay with our example, to be born with the DNA necessary to produce a living, “organic” work of art.

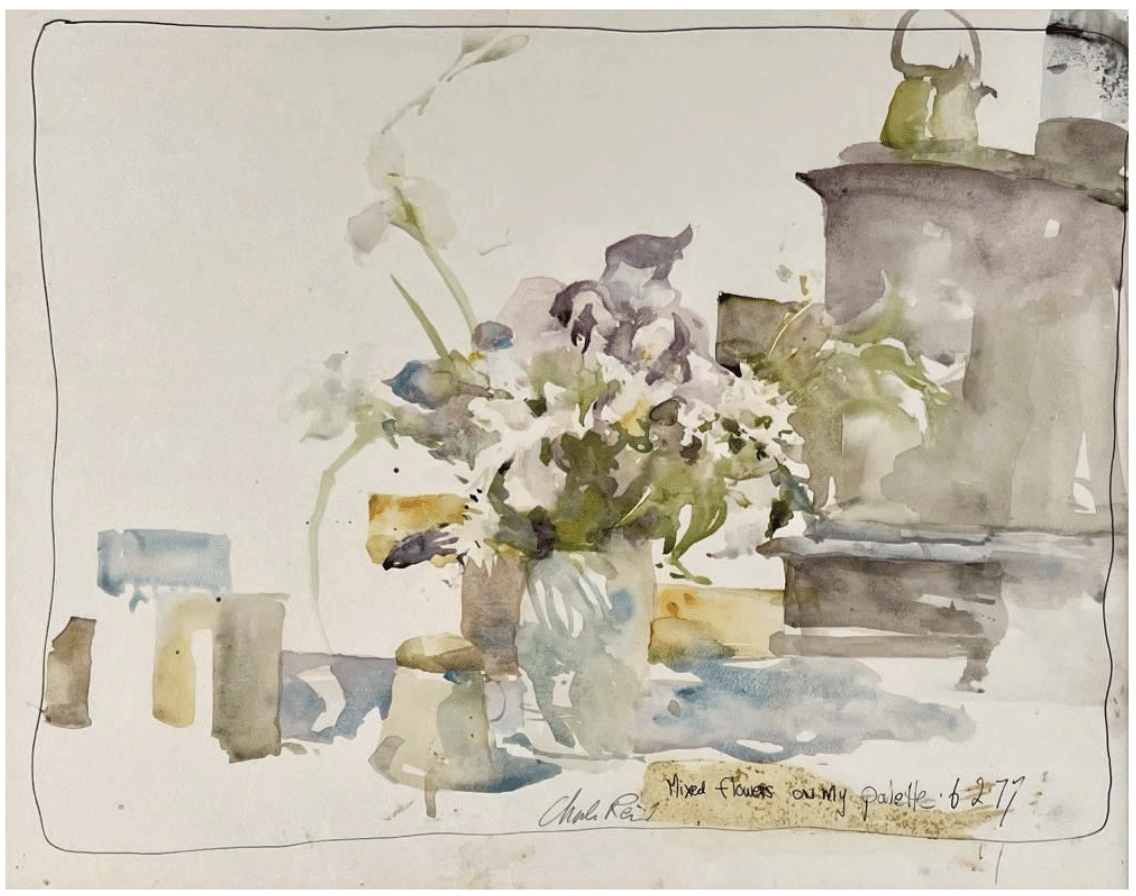

If theory isn’t as inspiring for you as actually painting (and who could blame you?) and you’d rather a hands-on tutorial about into bringing expression into your work, check out these instructional videos on painting expressive cityscapes and portraits and finding your voice as an artist.

To check out a teaching video from Charlie Hunter, master of the fading American icon, go here.

Watercolorist Charles Reid teaches a complete 10-lesson course in his video, available here.