Don’t let a lack of knowledge of composition hold you back from making better paintings. The key to developing an intuitive understanding of composition is not to memorize individual compositions but to internalize dynamic design.

It’s a truism that any drawing or painting is only ever going to be as strong or as weak as its underlying design. Without a strong abstract underpinning, you’re wrecking your paintings without realizing it. Even the greatest portraits by Sargent, Rembrandt, or Velasquez – paintings we tend to think of in terms of emotive content rather than form – rest on an invisible armature of geometric design decisions.

But you already know that without strong composition, your paintings are dead in the water. The challenge is what to do about it. How do you learn good design? There are lots of great videos out there that will teach you the essentials.

You can also learn a ton just by doing these two things:

- Study striking paintings – such as portraits – in which composition is largely invisible or seemingly subordinate to the motif (hint – it never really is!) and think only in terms of two-dimensional arrangements of shapes.

- Get a feel for how to create striking compositions by making small “thumbnail” sketches (about the size of a large postage stamp) or drawing then digitally on your computer.

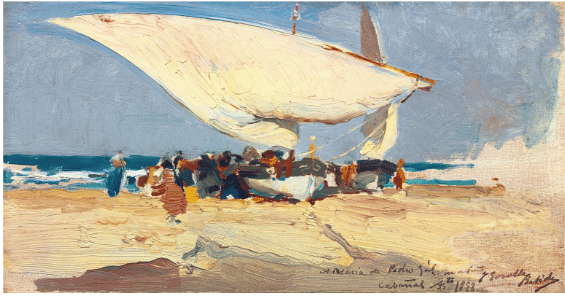

Joaquin Sorolla, fishing boat study, oil, 1898

Dynamic Tension

In the small plein air painting above by Joaquin Sorolla (sa-ROY-ya), “the Spanish Sargent” has brought what to him was an everyday scene – fishing boats coming and going near his home in Valencia, Spain – to the level of high art. He’s done this largely through the work’s feeling for bright light and open space, but also, if less visibly perhaps, by designing an incredibly dynamic underlying composition.

Dynamism in composition consists in pleasing tensions between contrary elements – big contrasts, bold coloration, large and tiny shapes in daring relationships with each other, diagonal lines shooting off in a variety of directions forming intricately balanced asymmetrical geometries.

As in Sargent, Sorolla’s ravishing use of light and color (see Thomas Jefferson Kitts’ video, “Sorrolla – Painting the Color of Light” dazzles the eye. This is a fairly flat work made of big shapes that make it easier to sense the underlying design, but try it on any painting and you’ll see it in play.

Look at that huge floating sail – how all its angles relate to each other and to everything else. In that sail’s powerful burst, all the gusty energy of the ocean gathers and billows!

At the level of overall design Sorolla literally connects that sail, through line and color, to the figures. An hourglass shape forms between two huge triangles balanced on their tips – the sail, swaying above and the sand in shadow below. Dynamism happens in how the sharp, swooping triangular lines of the sail’s edges and the rigging relate to the vast curvature of the sail’s upper edge and everything below the lower tip where the sail gathers in; how the wide white sail, which takes up so much of the composition, relates to the pale patches of open sky and then to the concentrated cluster of colorful figures bustling beneath it in the middle ground, as well as to the sand and shadows that stretch from and literally point up to it from the foreground.

When feeling out a composition, remember that all lines in painting are directional lines. The lines of a picture – by which is meant primarily the edges of the shapes – literally point the eye toward the main event (where the human figures, boats, sails, sea and sky all come together) by subtly angling up toward the middle from the sides and corners and down from above.

Before we leave this painting, I want to say something about how design relates to what a particular painting is about. All of these “dynamics” we’ve been studying here will work to enliven (or resuscitate, as the case may be) any painting, and the underlying principles are universal:

- you want to catch the eye from across the room,

- “move the eye through the painting” in a way that keeps the viewer from looking away, and

- maximize variety throughout.

And yet – beyond the technical aspects, composition contributes to meaning as well. I would argue that the dynamic rhythms of visual tension and release that Sorolla embeds here express Sarolla’s spontaneous feeling for the larger forces at work – the compressed, mighty energies where ocean, sky, and humanity meet. For me, that beautiful insight is what’s really at stake in this painting, and that’s what makes it great.

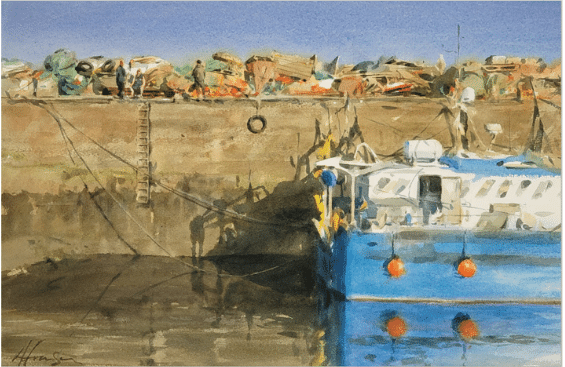

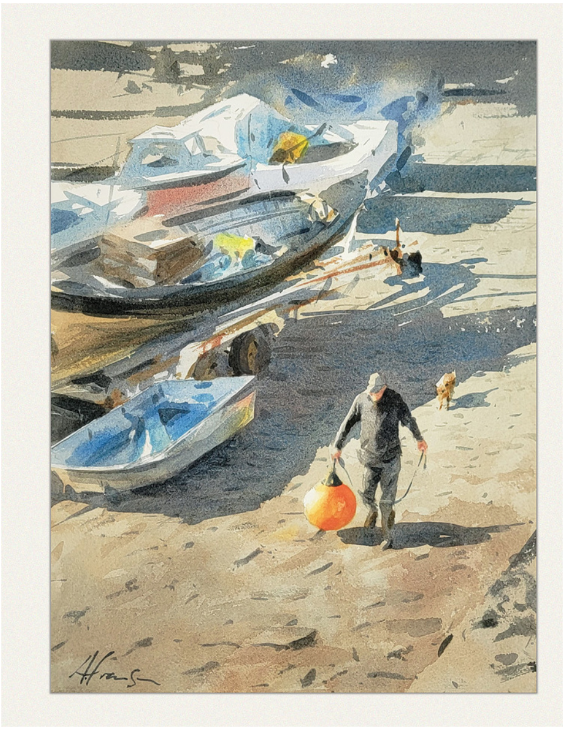

Andy Evansen, “First Mate,” 15 x 11 in., watercolor

Andy Evansen teaches his own design principles in the video, “Secrets of Painting: Watercolor Outdoors.”