NYC-based oil painter Devin Cecil-Wishing shares his thoughts on traditional painting and art as a language in its own world.

By Devin Cecil-Wishing

“As much as anything, I’m trying to get in touch with a way of thinking…perhaps that predates modern conceptions of what picture making is all about. Before the invention of photography, drawing and painting was the only way to create an image, and so it developed as a language of its own and began to create a world of its own behind the picture plane. It was a strange and quirky place, which oftentimes had very little to do with the appearance of the real world around us. It was a world that played by its own rules but, nevertheless, made sense.”

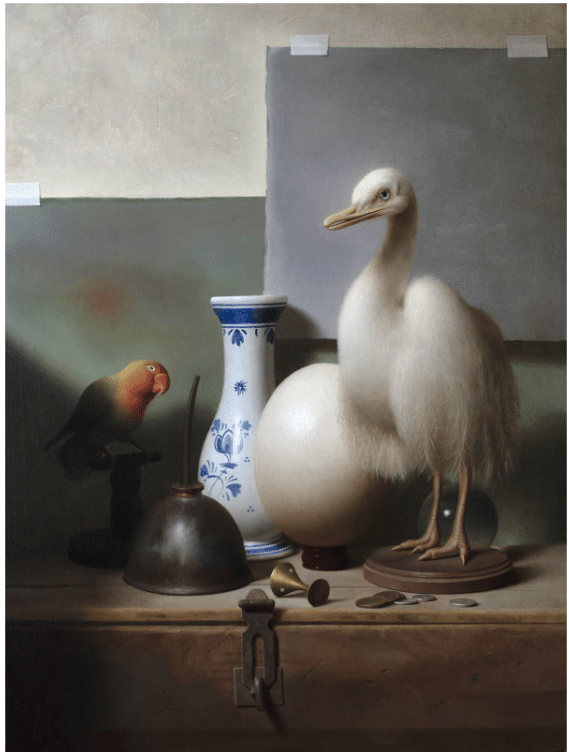

Devin Cecil-Wishing, “Rhea,” oil on linen, 24×18, 2023

“As you wander through a museum, you can almost come to view each painting as a window into this other world…Hundreds of years of art history can collectively come to be viewed as one body of work and each painting can become a window into different parts of this same world…each one made by different sets of hands and eyes, peaking in to see what part of this other world they can see.”

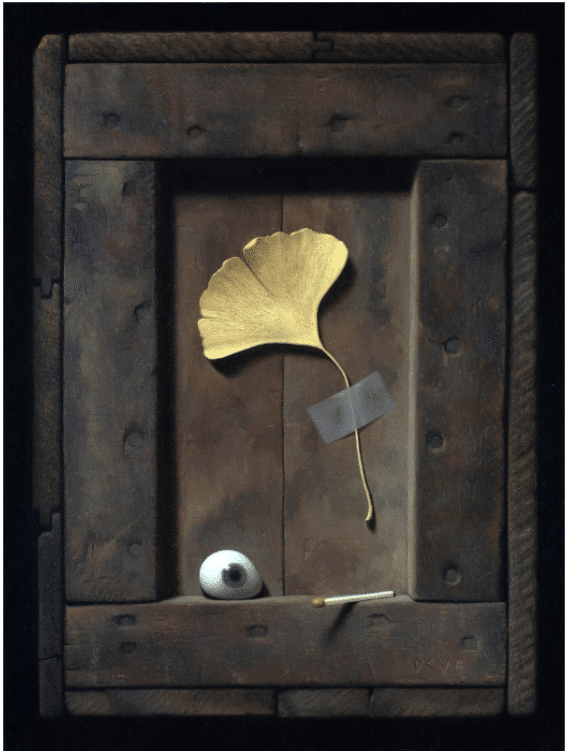

Devin Cecil-Wishing, “Ginko leaf,” oil on linen, 12×9, 2023

“Through the act of creating paintings, I’m able to act as an explorer, entering that other world and trying to understand it more and more deeply as a place, much like one might explore a new country or some uncharted part of the globe.”

Dutch and Flemish Influences

Devin Cecil-Wishing (b. 1981 in San Francisco) is an oil painter based in New York City who favors traditional methods for creating paintings. He works exclusively from life, memory, and imagination, choosing to avoid the use of photographic references, AI, or other such tools, based on the deeply held belief that the process of creation and the end product are intrinsically connected.

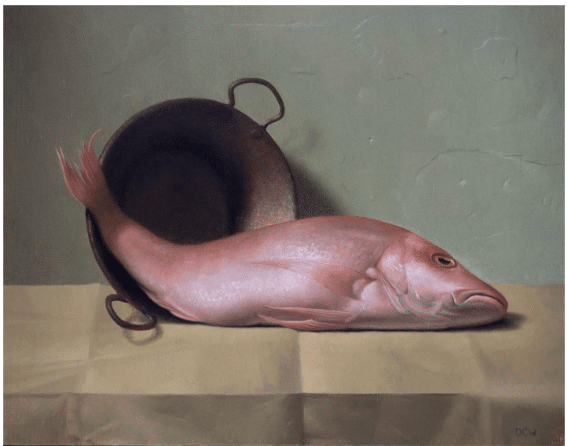

His work takes inspiration from many sources, but his largest influences are the Dutch and Flemish painters of the Baroque era and earlier. He has always been fascinated by the idea of depicting light and by the connection between light and emotion. In many of his paintings, the light effect can be considered to be just as much the subject of the painting as any of the objects being depicted.

Devin Cecil-Wishing, “Red Snapper,” oil on linen, 11×14, 2023

Devin grew up in San Francisco where he earned a BFA in illustration from the California College of the Arts. He later studied at the Atelier School of Classical Realism in Oakland, CA before eventually moving to New York City to become a full-time student at the Grand Central Atelier. He went on to become one of the core instructors at the Grand Central Atelier where he continues to teach. He also teaches workshops around the globe as well as online classes for students who are not based in New York. His work can be found in collections across the country as well as abroad and he has exhibited in galleries and museums from coast to coast.

Devin Cecil-Wishing, “Parrot Studies,” oil on linen, 9×12, 2023

Devin Cecil-Wishing, “Budgie with Asian Pears,” oil on linen, 9×12, 2023

To view his work or for more information on his teaching visit www.devincecil-wishing.com.

If you’d like to dive into some time-tested principles that will improve your approach to realist painting, have a look at Virgil Elliott’s video, Traditional Oil Painting: The Principles of Visual Reality.

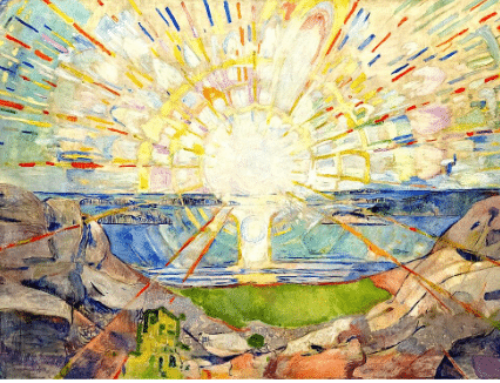

Edvard Munch’s “Lonely Ones”

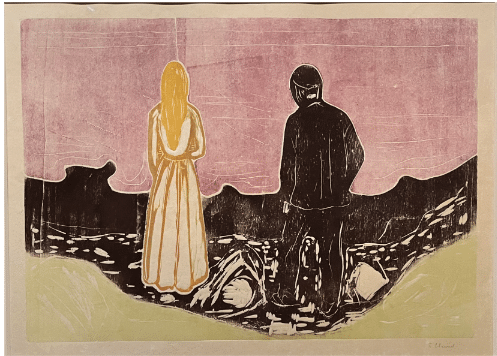

Edvard Munch, Human Beings: The Lonely Ones, 1889, colored woodcuts on paper

Swedish proto-modernist Edvard Munch ( ) explored many different mediums in his work, and woodblock printing remained one of his constants. The flattened picture plane and simplified forms gave the artist a very direct, uncomplicated forum for the play of expressive and symbolic forms.

One motif he repeatedly explored was a shoreline that featured a man and a woman seen from behind, looking out at an empty expanse of water. In Two Human Beings: The Lonely Ones (above), the pair do not touch or look at one another despite their proximity. Their anonymity and the title elevate the work to a statement about loneliness among humanity in general.

Five different versions of “The Lonely Ones” exhibited at the Clark Institute of Art in 2023.

Munch used a jigsaw method to create his woodblock prints. He started with one block of wood, carving the subject himself. Then he used a jigsaw to separate elements of the block. The man and the land were one piece of wood, the sea another, and the woman a third. After inking these parts separately, they were set together like a puzzle and painted. Munch could alter the effect of the composition by changing the palette on one or all of the carved pieces. The man, however, always remained black and woman white.

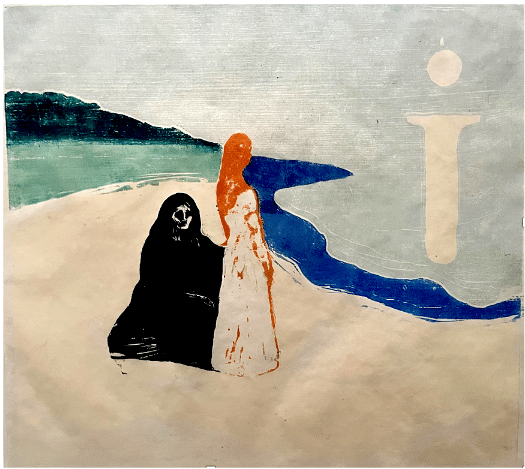

Edvard Munch, Two Women on the Shore, 1898, color woodcut and crayon on paper.

The impression of Two Women on the Shore shown here exemplifies the variety of effects Munch produced by inking his woodblocks with different colors.

In keeping with Symbolism, the late 19th, early 20th century movement his work inspired, Munch blends life and death in the two figures isolated here. He contrasts the two by color – the old woman, with her skull-like features, in black, the younger “maiden” in white. Most important though is that Munch fuses the two into a single shape; wrapping the death-like figure around the hem of the youthful figure’s dress implies that the old woman is like the shadow of the younger: Death is the shadow of Life, and the two move through this world together.

After cutting apart and reassembling the blocks for Two Women on the Shore, Munch used a stencil to paint the moon and its reflection onto the assembled block before making the print. This motif – the stylized reflection in the water with the circle of the full moon above it – appears in several of Munch’s most important prints and paintings. In itself it resembles an ancient symbol, something painted on the wall of an Egyptian tomb perhaps. But just what it symbolizes isn’t clear.