“Paint the flying spirit of the bird rather than its feathers.”

-Robert Henri

A chorus of frustrated painters’ voices ascends through the clouds on high to the ears of Apollo the Patron God of Painting, who leans over only to hear them crying out, as with a single voice in supplication:

HELP ME LOOSEN UP!

Odilon Redon, The Chariot of Apollo, 1905-06

What’s so great about painting loose rather than tight? Nothing really, except that we associate looser painting with a sort of state of grace, in which the artist lets goo of conscious technique and freely, seemingly effortlessly, handles the paint as a pure instrument of feeling.

This is really just a bias though. It’s worth remembering that Sargent’s bold “bravura” visible brushstrokes were often made toward the end of the painting, after days of “getting it right” in front of his sitter. They were only “top it off” flourishes, a conscious last step of extravagantly icing the cake.

It’s true that “tight” painting can look clunky, crowded, claustrophobic, cacophonous, cramped, and any number of other words beginning with “c” that suggest too much work has gone into it. There’s nothing wrong with tight, realistic painting. But overworking is different. Overworking is really what beginners mean by not painting loosely enough, and it’s one of the top problems developing painters face. It’s caused by two related things:

1. not having enough confidence – that is, meticulously going over a single portion of the painting, desperately trying to get it to “look right”;

2. not seeing the big picture clearly enough – by which I mean, the overall impression your viewer will get from the work. This is something too rarely considered. It goes beyond just being aware of composition and balance. It’s about keeping in front of your mind the spirit of the thing, the initial idea, the life of the painting, an overall feeling or “vibe.”

“Don’t just paint it, paint it doing something.” – Charles Hawthorne

Take bird painting. “There is a vast difference between a drawing aimed at recording an instant in the life of an alert organism and one aimed at showing how light falls on a stuffed specimen,” so said George Kirsch Sutton of the Wilson Ornithological Society. “A Bruno Liljefors would fully understand what I have just tried to say; so would a Jan Vermeer.”

Bruno Liljefors was Sweden’s most influential wildlife painter during both the 1800s and 1900s. His depiction of animals, particularly his famous bird paintings, remain timeless and influential to this day. His work was tirelessly accurate, and yet his details are just enough to convey both specificity and form, as well as action, movement and striking colour.

Bruno Liljefors, Common Swifts, 1886

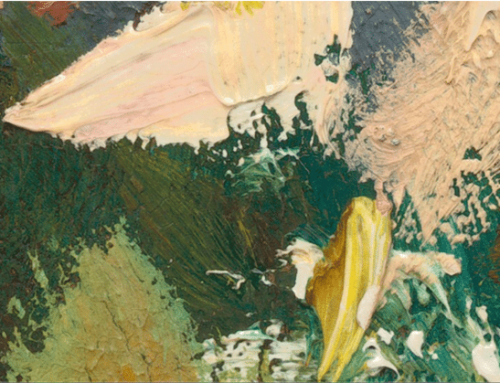

In Common Swifts (1886), Liljefors gives us super accurate representations of the birds and the wildflowers (it would be possible to identify each species he paints), and yet in each case the details are “just enough” – they’re not overdone. He didn’t have to paint every feather or blossom. This artist became famous for bringing wildlife painting beyond the domain of science and into an art in its own right. How? He kept the big picture in mind.

He didn’t just “faithfully” paint birds, animals and flowers, he painted them doing something. He brought them to life by investing them with motion and a feeling for their life and growth in the world.

Actually the two pitfalls mentioned above – forgetting the big picture and getting distracted and lost in details – both come down to confidence.

So how do you gain confidence?

- Obvious answer: paint a lot of paintings. Attend classes and workshops, online and off.

- Not so obvious answer: force yourself to pay more attention to the overall feeling the painting will convey.

Good painting serves intention, an overall “feeling-idea” or purpose in the mind of the artist. This expression of a state of mind or feeling-idea is separate from the degree of, on the one hand, faithful or skillful representation, and on the other, abstraction. You can have loose, abstract paintings that don’t convey much feeling, just as you can have tight, minutely detailed ones that do, and vice versa. It’s not about abstraction vs. realism.

“The Flying Spirit of the Bird”: two sculptures by Brancusi with increasing abstraction, from “Golden Bird” on the left to “Bird in Space” on the right. Both express soaring up into the sky.

The key is recognizing and prioritizing the work’s overall feeling, doing what it takes to bring it out, and subordinating details to it – that is, painting to express the feeling or life of the thing, and adding details only until they start to detract from that overall feeling.

You may or may not know the “feeling-idea” of a painting when you begin it. Often you can find it halfway through – a sudden idea for what you might be able to do for the viewer. For many paintings, the more training and practice you get, the better your chances of conveying that overall vibe. But remember the old adage too: a painter truly committed to putting skill at the service of feeling, someone like Rembrandt, could paint a masterpiece left-handed given a toothbrush and a tin of shoe polish. It all comes down to form and feeling.

Luis Azon is PleinAir Salon, September 2022 Winner1st Place Overall: “Late Afternoon in Spain” |

|

| Luis Azon, “Late Afternoon in Spain,” 52 x 52 in., oil |

| Luis Azon’s softly backlit “Late Afternoon in Spain” has clinched first prize in September’s PleinAir Salon monthly art competition. “This painting allows me to be quietly lost in a space while I hear activity all around,” judging artist William A. Suys, Jr. said of “Late Afternoon in Spain.” “I’m able to separate from viewing a surface to sensing a feeling of atmosphere while mentally passing in and among groups of people engaged in their individual worlds as they become part of a unified environment.”

Entries are being accepted for this month’s completion now. In the paint, Chris |