Though you may or may not have any in your kit, some higher-end pigments, including carmine lake, also known as crimson lake, are still made the old fashioned way: by crushing up bugs.

Cochineal, found in Mexico, was brought to Europe in the late 16th century. A scaly parasite found on certain species of cactus, it’s a species of the lac family of insects. The lac insects secrete a waxy resin that is still harvested and converted commercially into lacquer and shellac and used in various dyes, lipsticks and blush, food dyes (cochineal or carmine extract figures in red and pink foods like catsup and strawberry yogurt), wood stains, varnishes, and polishes.

No Lac of Resin

Shellac is made from resin secreted by a lac bug onto tree branches that are processed into dry flakes.

The word “lacquer” itself stems from the Sanskrit term Laksha, which represents the number 100,000. It was used for both the lac insect (because of their enormous numbers) and the scarlet resinous secretion the bug produces, according to the Oxford English Dictionary. Thus, the word shellac, a resin produced by the prolific lac insects from the sap of an Indian fig tree.

The lac family of insects also gave its name to “lake” colors, such as “indigo lake,” which we still see on paint tube labels. A “lake” pigment is one that’s made by dispersing bits of any organic compound (as opposed to the inorganic chemicals in, say, ultramarine blue or cadmium yellow) that has been chemically stabilized to be more permanent than otherwise.

In its earlier form, cochineal faded rapidly in sunlight. Its first replacement was madder lake, which is made from the red roots of the madder plant (used for ages as a fabric dye and also still available as a pigment).

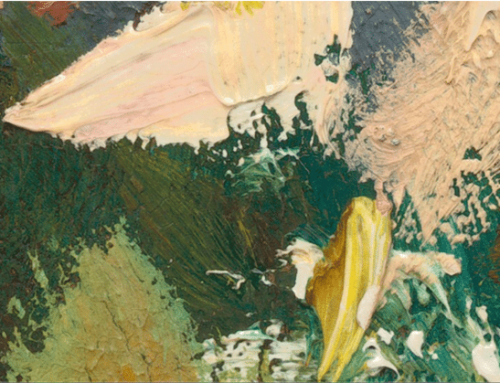

George Seurat used madder lake in his Vase of Flowers, 1879-’81, in the collection of Harvard University.

The next successor was madder’s offspring alizarin, the red colorant isolated from madder and developed during the 19th century into the relatively stable alizarin crimson pigment in widespread use today.

Expect to see new cochineals coming onto the market soon, though. Scientists are finally getting around to synthesizing the active chemical (carminic acid) responsible for the insect’s brilliant scarlet secretions in the lab.

So we’ll perhaps come full circle to the heady time when the crimson made from insects first spread across the world “like wildfire” during the 17th century, when, in the words of Smithsonian Magazine, “it funded empires, stained religious garb and was showcased in masterpiece paintings — becoming a precious commodity rivaling silver and gold.”

Color is the subject of Thomas Jefferson Kitts’ video, Painting the Color of Light, in which Kitts breaks down the spectacular effects achieved by Joaquin Sorolla, known sometimes as “the Spanish Sargent.”

Alone Together

Edward Biberman (1904–1986), Tear Gas and Water Hoses, 1945, Oil on canvas, 29 x 36 inches, The Schoen Collection, American Scene Painting

Opening Sunday, May 29 at The Westmoreland Museum of American Art in Greensburg, PA, the exhibition Alone Together: Encounters in American Realism brings together works of art separated by almost a century to consider how they are bound together by the shared experience of living and working in difficult times.

The works from the Schoen collection are supplemented with key loans from other institutions, including Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, as well as with selections from The Westmoreland’s own permanent collection. Alongside these historical paintings and prints, which are predominantly from the 1930s through 1950s, the exhibition stages encounters with works by five contemporary artists to capture shared experiences across time.

Many of the works in the exhibition are characterized by their dream-like vision of the social realm rendered with precise technical skill.

Alone Together: Encounters in American Realism will be on view at The Westmoreland from May 29 -September 25, 2022. A schedule of public programming related to the exhibition, including a panel discussion, artist talk, culinary experience, and film screening, will be announced soon in the Museum’s Spring/Summer 2022 Perspectives newsletter and posted at thewestmoreland.org/events for registration.