Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011) broke into the boy’s club of macho mid-century Jackson Pollock-style Abstract Expressionism (AbEx for short), but she’s still not as widely known as her peers.

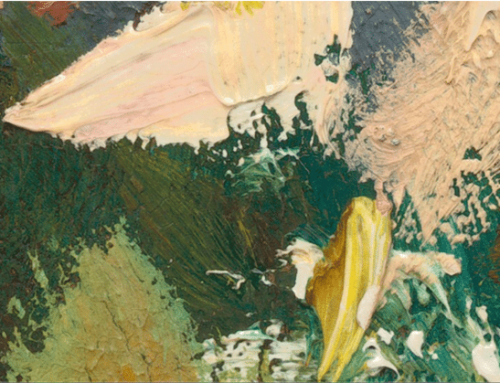

In her sandy, windswept studio in the Cape Cod dunes, with her creative energy at fever pitch, Frankenthaler stained unprimed canvases with fields of color the way Rothko did, pouring diluted pigments from above giant absorbant canvases laid out on the floor.

Yet there’s nothing random here. Hers was the opposite of a flippant, aggressive, shock-tactic – this was a carefully controlled partnership with chance. Frankenthaler tamed chaos and rode it like a docile dragon.

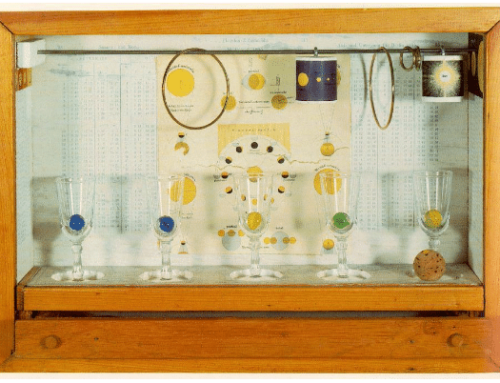

Although art history has focused on her “soak-stain” technique, she also sculpted, made ceramics, and practiced a wide range of printmaking including woodcuts, lithography, etching and screen printing. Her woodcuts (traditionally a precision process about as far from spontaneous paint-pouring you can get) are being exhibited for the first time en mass in London this month.

“Just look at the pictures”

She had a stormy affair with Abstract Expressionist kingmaker, the critic Clement Greenberg (who famously championed Pollock, among other New York School painters) and later married one of the movement’s leading painters (Robert Motherwell). Frankenthaler’s work speaks for itself though. To appreciate it, we need to what Pollock said he wanted – stop trying to impose old-school judgments and art-world-politics and “just look at the pictures.”

But the thing is, you don’t look at Abstract Expressionist pictures the way you look at traditional Western representational art. AbEx radically challenged the Western tradition by rejecting pictorial content in favor of allowing the paint and how it’s applied to do the work of expression.

Here’s what Frankenthaler did:

· Adapted AbEx for her own purposes

· Worked in partnership with chance (by combining conscious choice with pouring the paint and manipulating the canvas)

· Embedded emotional and spiritual content by referencing the landscape, an approach that radically departed from AbEx and also challenged and transformed the landscape tradition itself.

I didn’t fully understand Frankenthaler until the Provincetown Art Museum showed some of the dozens of paintings she’d made during summer residencies on the Cape – the colors, I realized with a shock, were the same ones I was mixing for the plein-air class I was teaching there. Hers were totally abstract paintings, but I was looking at landscapes – not traditional ones, but landscape paintings of an entirely new order.

These works seem created by the felt experience of the landscape, direct expressions of the artist’s emotional embrace of her environment’s colors, shapes, and moods, and not without the ragged truth of the world’s ungovernable mysteries.