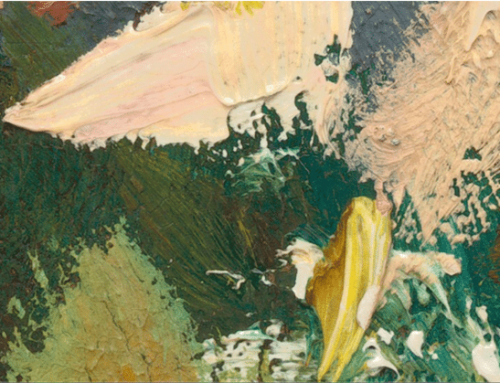

Unless you know how to read a painting, this oil by Clement Nye Swift appears to be nothing but a pleasant, if typical, landscape painting. In fact, View of the Acushnet River seems like it’s got even less going on in it than your typical late 19th or early 20th century landscape.

Perhaps when viewing landscape paintings, we’re not in the habit of thinking, What does it mean? But whereas nature in itself might not “mean anything” (what does a tree “mean”?) paintings are the products not of nature but of human minds and hearts; paintings reflect an individual’s perception of nature and his or her conception of what art is all about. So, in art the possibility of meaning (or the lack thereof) is automatically in play.

It’s not necessary to know a lot about the artist in order to read a painting. But just to give him his due, because he isn’t well known today, Clement Nye Swift (1846-1918) was an accomplished turn-of-the-century artist. He was both born and buried in Acushnet, Mass. after a successful career spent mostly as a Salon painter in Normandy and Paris, France.

Clement Nye Swift, View of the Acushnet River, c. 1900

So what do we see in this painting? It’s almost a “pastoral” painting of peaceful cows in a bucolic setting – except that it isn’t. First of all, it’s not a bucolic setting (where are the lush fields, picturesque paths, and full, leafy trees?). Sharp eyes will pick out puffs of smoke on the horizon rising from a gray line of city-scape smokestacks spanning the horizon.

Smoke on the Water

Second of all, Swift’s landscape is too brown and dead-looking for an idyllic pastoral scene. The sky is flat – devoid of anything like a cheerful blue, or even a clearing (or gathering) storm; it’s just blank. The hilltop is flat, with little to break up the horizontality except the cows: There they sit and stand, exposed on their grassless hill unrelieved by conventional framing devices such as trees or even a weathered barn. Their watering hole has shrunk to a muddy patch of weeds.

Here’s what the New Bedford Whaling Museum, where the painting is kept, has to say: “Similarly to the End of Whaling, Swift demonstrates a critical view of the industrial age in New Bedford. The green pastures of (previous depictions of the site) painted 50 years earlier have given way to a brown, dry landscape and broken fenceposts with smoke stacks churning out lines of black smoke along the mill horizon.”

That Swift is up to something is confirmed by comparison to a sort of companion picture, painted some 10 years later, of the same river, a painting titled The End of Whaling.

Clifford Nye Swift, The End of Whaling, 1910

In this painting, the meaning is plain. Listen again to the curator:

“In this melancholy and powerful painting, Clement Nye Swift has captured the decline of the great age of whaling in the city of New Bedford and the concurrent rise of the age of industry. As the smoke stacks along the Acushnet River dominate the waterfront and cloud the skies, an old man sits dejectedly by a broken down whale boat, both now obsolete. Weeds and small trees grow through the split boards, and the rudder lies useless on the ground. Ten years after Swift painted this work, the last New Bedford whaleship, the Wanderer, left the harbor only to wreck on the shores off Cuttyhunk fewer than 20 miles away.”

Reflecting a sad end to a proud age of promise, the scowling old whaleman in The End of Whaling slumps with head in hand while the relentless symbols of industry crowd and gather behind him.

Clement Nye Swift, The End of Whaling, 1910 (detail)

If any more words are needed, here is a vivid description of the former American whaling capital at the time:

“Wrinkly-eyed old men paced the wharves gazing seaward, and every day was hushed as a Sabbath morning for the business of the town had moved away from the waterfront,” recalled Clifford W. Ashley in his historical account, The Yankee Whaler.

So time and tide wait for no-one, and artists in their paintings tell the many stories of our world.

Contemporary painter Nicolas Coleman explains in a newly available video how he embeds the elements of story in his Western-themed paintings.

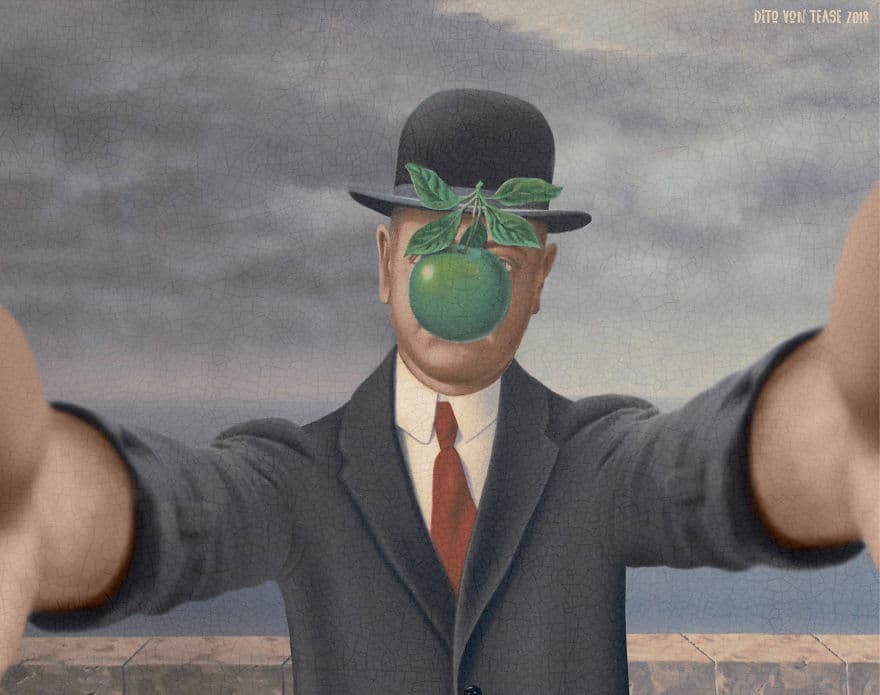

If Famous Faces from Paintings Were Selfies

Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring on a break from posing to take a selfie.

An archived post by Dito Von Tease on Bored Panda gathers several examples of some of the most famous classical portraits and self-portraits in the world in poses typical of modern selfies and dubs them new works of art in their own right, “reborn within the digital ecosystem of social networks.”

Rene Magritte’s Son of Man doesn’t need a painter to make a pic he can post on his social.

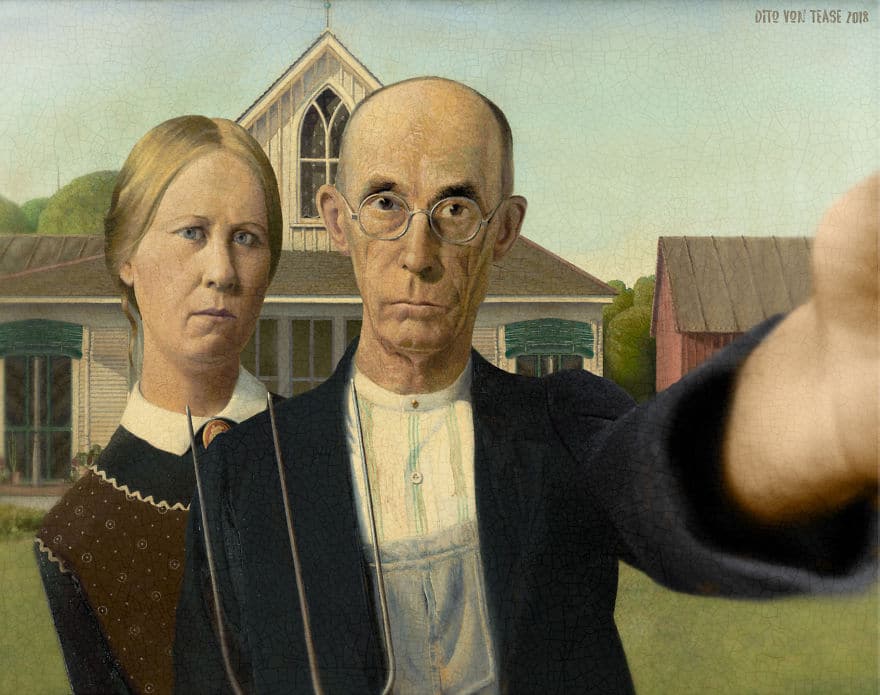

My favorite might be Grant Wood’s American Gothic couple. It kind of looks like they’re staring at the imaginary phone. See all the rest here!

American Gothic Selfie

In the Paint,

Chris