What Makes This Painting Great? An occasional series all about analyzing what makes paintings beautiful, iconic, memorable, or effective.

Painters, beginners and masters alike, make leaps and bounds by studying creative triumphs of the art. What kind of principles, techniques, compositional designs or color choices have artists used to create your favorite paintings?

Italian Post-Renaissance painter Giuseppe Cesari painted under the name Cavaliere d’Arpino, which literally means “Knight of Arpino,” the town where he was born. The flashy name-change probably didn’t hurt Giuseppe’s rise as one of Rome’s most fashionable painters among early 17th century connoisseurs.

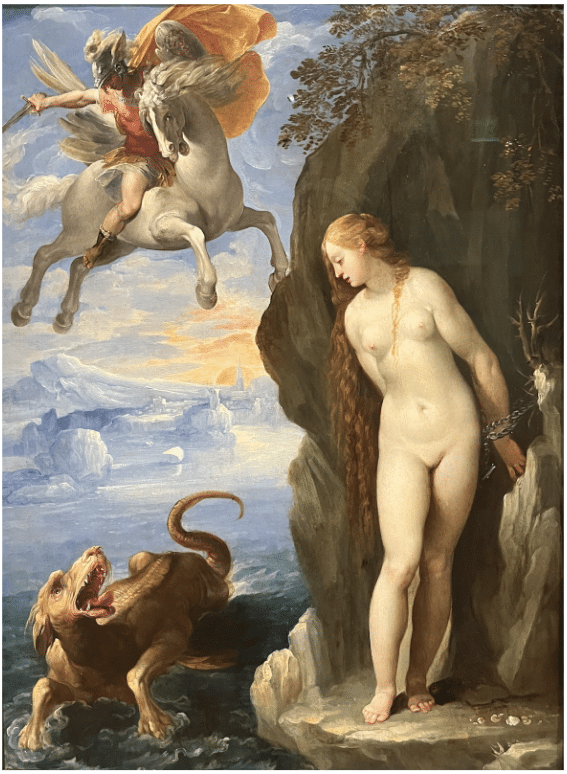

When Arpino painted “Perseus Rescuing Andromeda,” wealthy patrons were snapping up his small-scale mythological vignettes such as this one. During this time in history, artists began working outside of church commissions to decorate newly built marble halls and country villas.

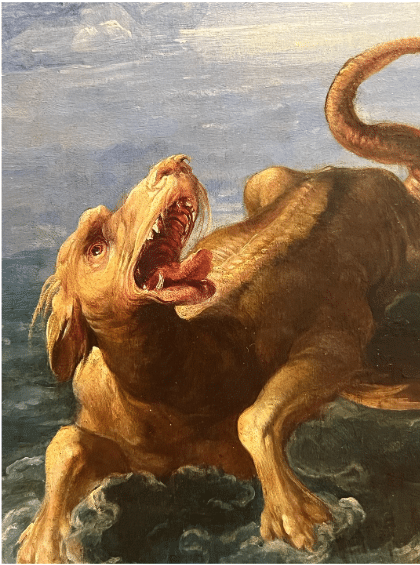

DETAIL: The sea monster (for which Cavaliere d’Arpino probably used his DOG as the model!) in “Perseus Rescuing Andromeda,” oil on panel, c.1595 (approx.. 25 x 30 in).

Arpino is considered a “Mannerist,” so named for a stylistic period in which successful artists’ personal styles or “manner” began to edge out classical restraint. This was a transitional period away from the high Renaissance fusion of classical philosophy and humanism (think Botticelli, Michelangelo, or Raphael) advancing toward the Baroque style, associated with painters like Caravaggio, whose work is full of realistic action, high-contrast intensity, and drama. Arpino applies enough of those qualities to place him closer to the Baroque than the Renaissance, but his palette and the underlying message of his painting, as we’ll see, is classic high Renaissance through and through.

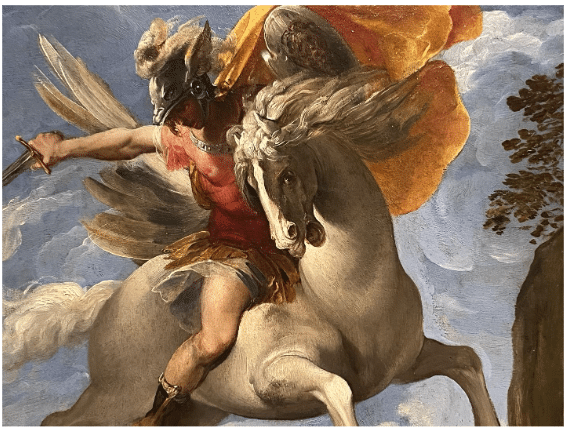

DETAIL: Cavaliere d’Arpino, “Perseus Rescuing Andromeda,” oil on panel, c.1595 (approx.. 25 x 30 in)

Why should I care about this painting?

Paintings like this set the stage for the next 200 years of European and American painting. And while Arpino’s “Perseus Rescuing Andromeda” is indeed a vivid and striking example, full of breathtaking beauty, intensity, and drama, also knowing what it’s “about” makes it even more interesting.

Arpino’s painting shows the Greek hero Perseus swooping down from the sky riding on Pegasus, the winged horse. Perseus is rescuing Andromeda, a princess who is chained to a rock, from being sacrificed to a sea monster by her father, a superstitious king.

And yet, despite the subject, Arpino creates a carefully balanced, fully classical work. The hero’s face is shaded, but even so we can see he is completely calm, focused, fully in control of his actions and his emotions.

And how about the face of Andromeda as she eyes the monster? Have you ever seen so chill a princess in peril?

Why does Arpino present her and her rescuer this way?

At the time Arpino painted, the tale of Perseus and Andromeda (one of the West’s original “knight slays dragon, saves and marries the princess” tales) was seen as an allegory, a story symbolic of the triumph of good over evil in terms of the qualities of Godliness, Reason, and Logic overcoming Sin, Madness, and Error.

Polykleitos, “Doryphoros” (Spear-Bearer), c. 450 B.C. one of the best known Greek sculptures of Classical antiquity, depicting a standing warrior, originally bearing a spear balanced on his left shoulder.

The original ancient Greek artists and sculptors often portrayed their mythological heroes and even warriors with perfectly calm, beautifully composed faces with idealized features signifying the triumph of Reason over barbarity, the ideal balance of mind, body, and emotions. In doing the same here for Perseus and Andromeda nearly 1,000 years later, the Baroque painter is being true to the classical Hellenic ideals that so influenced Rome and, thereby, Western culture as we know it today.

Roman Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius, bronze, 175 A.D.

How’d They Do It?

Like most painters of the time, Arpino painted in layers over dry, previously applied paint. He used a wood panel, probably prepared with gesso containing marble dust that would “illuminate” the painting by reflecting light back up through the paint.

First he would probably have created a “cartoon,” that is, a freehand monochrome drawing on the canvas, and gradually built up depth and color over several lengthy sessions at the easel.

Arpino used Leonardo da Vinci’s invention of aerial perspective for the distant city of Joppa, visible in the painting’s middle section.

Arpino’s aerial perspective (left) compared with Leonardo’s (right)

Arpino was careful to hide his brushstrokes when painting smooth surfaces, such Andromeda’s flesh. However, he let himself go and created more vigorous painterly textures when drama and movement were called for, such as in the horse’s flowing mane and tail, as well as in the cloud-swept sky.

DETAIL: Cavaliere d’Arpino, “Perseus Rescuing Andromeda,” oil on panel, c.1595 (approx.. 25 x 30 in)

By bringing back the classical idea of the victory of order, balance, and reasoned truth over chaos, Arpino was advancing the Renaissance project of reinvigorating the “dark” Middle Ages with ideals that would guide succeeding generations of European civilization right through to the founding of America. We can find some distant cousins of heroic Greco-Roman horsemen in the following: 1. Napoleon 2. Napoleon, 3. George Washington.

”Napoleon Crossing the Alps” on horseback by French neoclassicist Jacques-Louis David, 1800-1801 (left), additional oils of Napoleon on horseback, 1810, (center) and of Washington Receiving a Salute on the Field at Trenton, painted by Fohn Faed in 1857 (right).

Overall, though the artist isn’t a household name, Arpino’s 1595 painting of Perseus arriving to save Andromeda from the sea monster provides a solid glimpse of the thrilling ways paint has been used throughout history. Appreciating a work like “Perseus Rescuing Andromeda” reminds us what great painting looks like, even as it helps us understand how our world became what it is today.

Horses play a big role throughout the history of Western art, from ancient classical times to contemporary realism. If you’re interested in learning how to paint horses, check out Johanne Mangi’s video, The Fine Art of Horse Painting.

If Great Art Thrills You, Take the Fine Art Connoisseur Trip to Venice

Regatta on the Grand Canal

Giovanni Antonio Canal (1697-1768), known as Canaletto

Each year, Fine Art Connoisseur Editor Peter Trippi and I lead a group of art enthusiasts, collectors, and artists through a region of Europe to go “behind the scenes” in the art world. Our next trip, October 20-29, includes six nights in Venice and three nights in Verona, a must-see art adventure not on many people’s radar.

On a typical trip we visit art museums, often privately and behind the scenes with the help of curators and directors. It’s not unusual for us to find ourselves in private homes, visiting with artists or viewing private collections, touring the artwork in churches, or having gourmet meals, as well as enjoying multiple memory-creating unique experiences rarely available to those touring on their own.

Venice promises many special adventures in a city rich with culture, with art created across generations. Due to limitations on our scheduled events, seating is especially limited for this tour. It is recommended that reservations be booked now (also, this is the time to save by advance booking on flights).

This trip does not include airfare, but includes hotels, touring transportation, and most meals. This is a very high-end, VIP-level luxury trip. Art lovers and spouses are welcome. Booking deadline: May 15 or while seats last.

To sign up for the trip, visit www.FineArtTrip.com.