Sometimes it takes a structured assignment to motivate your brush. Other times, a creative exercise coming from out of left field can get you out of a rut, freshen your approach, shake up stale routines, and reinvigorate your love and excitement for your art.

Today master watercolorist (and teacher for 30 years)

Stan Miller shares six of the prompts he uses to get his students into creative mode. Beginners and seasoned painters alike will find value in these challenges.

Six Creative Exercises to Spark Inspiration

BY STAN MILLER

1. Print out an image of something you want to paint, do the painting with the image and your painting upside down. Painting upside down helps you paint what you actually see, not what you think is there. It allows you to see drawing, proportion and value errors much more easily too.

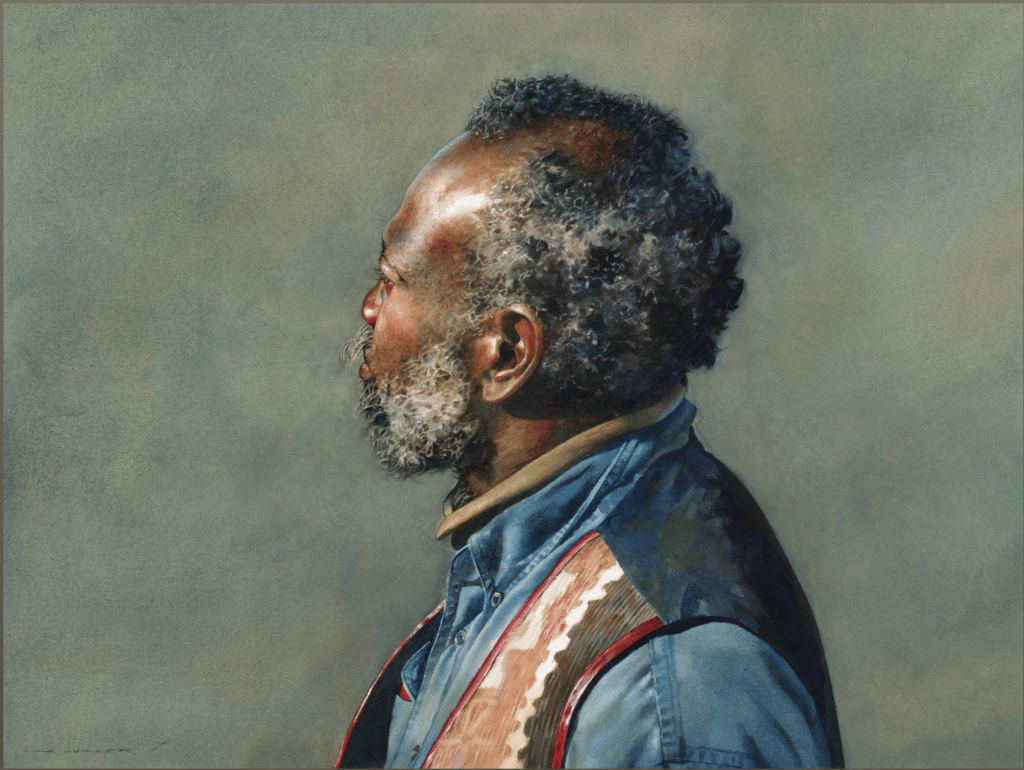

Stan Miller, Profile of Charles, 19″ x 26,” watercolor

2. Do a painting about 11 x 14 inches, completing the painting only using 100 strokes. Another one, using only 50 strokes. Another one, using only 10 strokes. This teaches us to edit and simplify. In writing, a similar assignment might be: Tell me about your life, in 100 words, in 50 words, in 10 words… this is how a writing instructor might teach a student to move away from descriptive writing into more poetic territory, and it works for painting just as well.

3. Do a painting by gridding a reference image into 16 squares. Grid your canvas into 16 corresponding squares and, observing carefully, paint one square at a time. This can also be done by gridding your image into 100 squares, or 50, 24 or even just four squares. Much like painting upside down, this exercise gets around the mental noise and teaches us to more accurately paint what we are observing.

4. Limit or expand the time spent on a painting. Do a small, perhaps 4 x 6 inch painting, with a small brush and spend a minimum time of 3 hours on the painting – or 10 hours on a 4 x 6, if the image is complex enough. Alternately, spend just one hour on a painting that is large, perhaps 18 x 24 or 24 x 36 inches. This teaches us different styles of brush and paint handling and different styles of painting altogether. Use a timer when you do these.

Stan Miller, Venice Shadow Light, 12″ x 14,” watercolor

5. Work from a black and white image but paint the image in color. The beauty of this one is that the color can’t be incorrect, because it is imaginary. Just make sure the drawing and the values are correct. Use a minimum of at least five colors.

6. Do an entire painting using only three colors, red, yellow and blue…learn to mix these colors to get as many other colors as you need – or can imagine.

Thanks to Stan Miller, there’s a simple process for how to choose a portrait subject and style of painting that matches your skill level perfectly. Learn more in the video workshop

“Watercolor Portraits.”—-

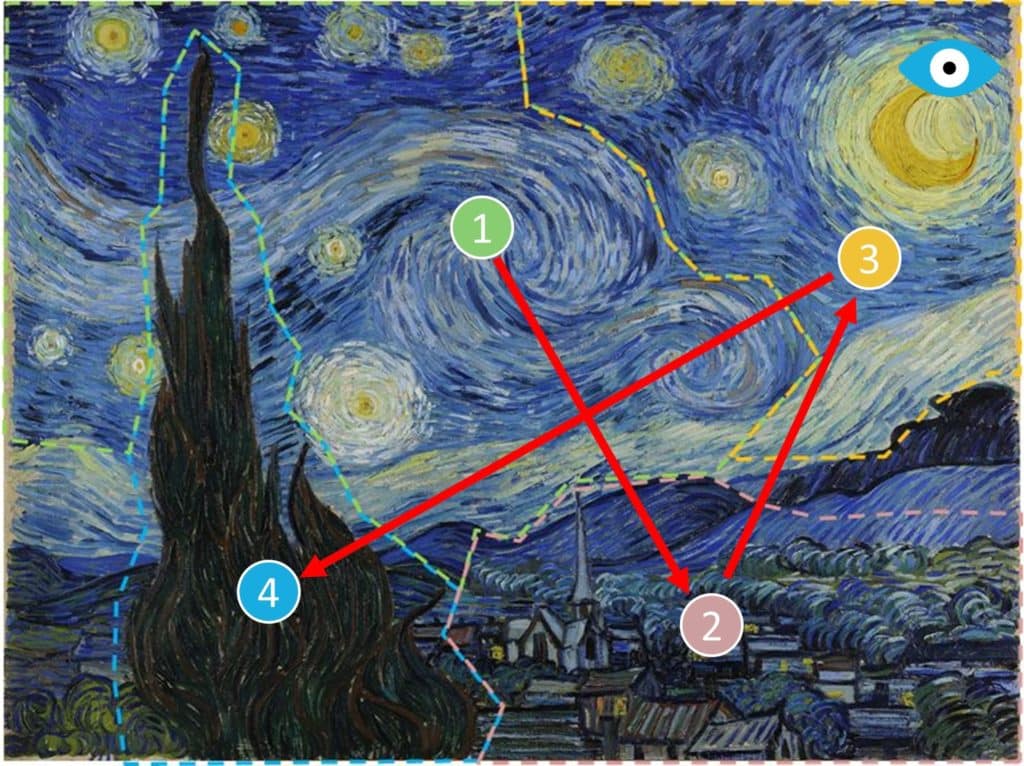

How We Look at Starry Night

In the largest study conducted involving eye tracking in art, we learn just how “The Starry Night” pulls us in.

BY DR. DAN HILL

Author of “First Blush: People’s Intuitive Reactions to Famous Art”

In 1908, the same year that Gustav Klimt created “The Kiss,” eye tracking was born. Back then, the tool was cumbersome as hell—requiring enough invasive bells and whistles to make test subjects look like they were going deep-sea diving. Fortunately, the tool has gotten a lot easier to use since then. Plop a person down in a seat in front of an eye-tracking machine, and you can precisely capture—on a split-second basis—where exactly a person is looking. The set-up takes usually no more than half a minute. During the set-up calibration period, participants are asked to follow the bouncing red ball on screen so that the machine can quickly learn where precisely to find their eyes. Then the test can begin.

In van Gogh’s case, “The Starry Night” is more or less the view that the artist had from his asylum window in Saint-Rey-de-Provence after cutting off his ear. I say “more or less,” but it’s actually more. That’s because van Gogh added an idealized village.

Participants naturally took a variety of paths in looking this painting over. But on average, where did they tend to go with their eyes? First up was the biggest swirling vortex in the sky. Next up was the slumbering village. That stop along the gaze path was followed, in turn, by participants looking at the moon. Finally, they took in the large cypress tree in the foreground that parallels the church’s steeple.