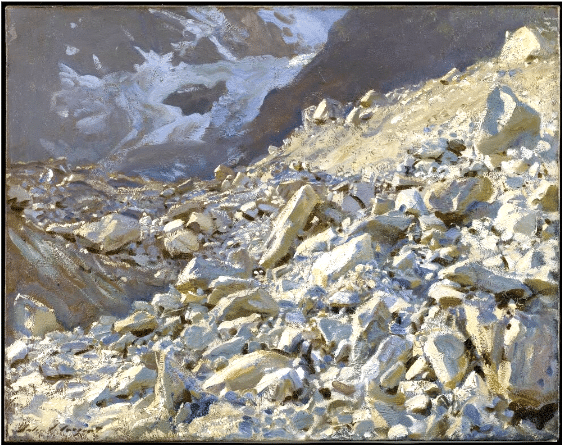

The painting above is by John Singer Sargent. It’s titled simply “Moraine” or “The Moraine,” which is so blunt and literal that we can assume the artist was more interested in the lights, shadows, and textures of the terrain than in anything more lofty. He probably took this painting on as a challenge and wanted his audience in turn to see it as a brilliant tour-de-force of observation and technique. Which it most certainly is.

There is feeling in it, though, as there always is in Sargent. The artist has composed this painting so that the shattered rocks lead us down a walled ravine toward a slope or chasm, beyond which the active glacier waits. The snow back there on the further glacier has a strange swirled shape, like churning sea foam. One can sense, in the stilled cascade of shattered rocks, something of the immensely powerful forces that underly nature’s beauty. In the watercolors and plein air landscapes like these though, it’s as if Sargent is saying, “Look! Just look at how incredible and beautiful the world is!”

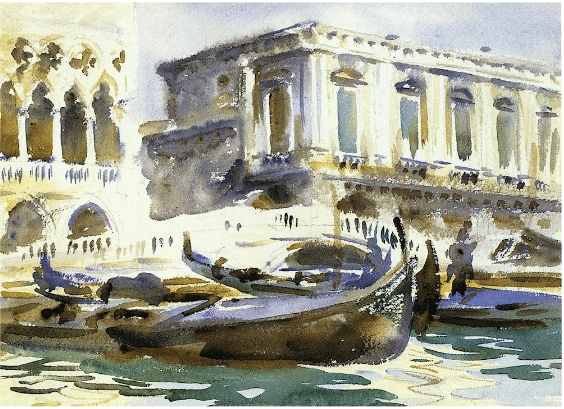

The many bright warm highlights and cool blue shadow tones recall many of Sargent’s breathtaking exercises in white on white (such as “Ambergris”) His watercolor rendering of the municipal prison in Venice (below) shows the same impulse. If ever a painter was in love with light, John Singer Sargent was one.

Prison, Venice, watercolor

A moraine is a mass of rocks and sediment carried down and deposited by a glacier. In other words, it’s a random pile of rocks. That’s partly what makes Sargent’s rendering of the maoraine’s chaotic, and to many an eye featureless topography, so worthy of our attention. It’s an outstanding example of a not very picturesque subject turned into an incredible painting.

The lesson here, and it should be an inspiring one, is that it’s not what you paint, it’s how you paint it. To be able to paint something in such a way, naturally you have to see it that way first. Developing your own artistic eye and learning how to get more of yourself into your painting is generally a lifelong process. Just how much of himself did Sargent bring to the table? Well, if you could have stood where he was standing and seen what he was looking at, you would have seen something like this:

Moraine till in Svalbard, Norway (photo by Dr. Karen Kleinspehn) source: jesse.usra.edu

That’s a typical moraine in Norway (Sargent’s is somewhere in the Swiss Alps). There’s quite a world of difference between the near-featureless Norwegian landscape and a painting by Sargent. Certain artists, and Sargent is a great one for this, teach us to keep the doors of our perception open, so that perhaps we too can see the marvelous in the ordinary.

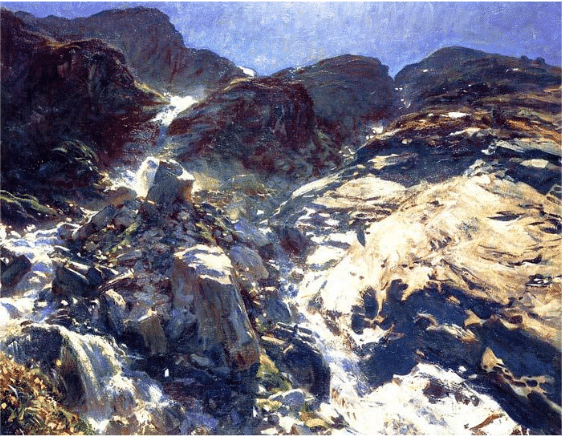

Although he’s thought of mostly as one of the leading portrait painters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Sargent evidently loved to paint nature. He was on vacation in the Swiss Alps in 1909 when he painted “The Moraine.” Around that time, he painted a similar work, “Glacier Streams,” also known as “The Indomitable Glacier” (below). Incidentally, this latter painting is housed in the Springfield Museum of Art in Springfield, Missouri. And it’s another stunner.

John Singer Sargent, Indomitable Glacier, Oil on canvas, 87.95 x 113.67 cm (abt. 30 x 40 in.)

In terms of composition, in “Indomitable Glacier,” (I strongly suspect this is a made-up title, something a dealer or curator added along the way) we have another very original variation on standard approaches. Sargent shoves us in close, right at the bottom looking up, without stable ground to stand on. The design seems to have a center of interest in the lower right quadrant, where the light is striking the sloping rock, casting an arc of vibrant blue shadow behind it, but the overall effect is convergent motion.

Our gaze bounces all over this canvas, zig zagging up, down, across, and back, between like a pinball between scattered, multidirectional edges, lights, and shadows. The effect of the largely angular abstract design in both “Glacier” and “Moraine” is to intensify visual energy. Compared to these two, the primarily horizontal arrangement in the watercolor of Venice makes for a calmer, if still lively, painting.

Sargent’s landscapes are far more than studies, but they’re nothing like the “pictures” that audiences of the time would have expected and admired. Sargent isn’t really interested in conveying Impressionistic lyricism or Romantic/Hudson River “majesty” here. What traditional, approved academic formulas do you see being applied to any of this subject matter? Yet, they’re all knockouts!

In landscapes like these, Sargent reveled in combining his uncanny skill at capturing light, shadow, and texture with spot-on color-values. But plenty of other artists have had that same skillset, and we aren’t talking about them. Why?

Because Sargent had an exciting way of seeing nature and people. What makes his landscapes so compelling is what he feels and what he makes us feel through them.

Sargent’s landscapes show how an energized feeling for the beauty and vitality of the world can make even a pile of broken rocks sing.

Design plays a primary role in Sargent’s originality and effectiveness as an artist. If you could use a primer or two on composition, check out one of these videos.

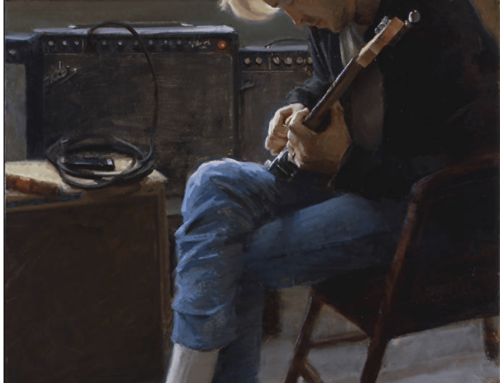

If you’re interested in learning how Sargent painted, have a look at Jefferson Kitts’ Sargent, Techniques of a Master.

Top Watercolors on Exhibit in NYC

Throughout the rest of the month of April, New York City’s venerable Salmagundi Club will host the 157th International exhibition of the American Watercolor Society. The exhibition features 148 artists from around the world working in a variety of watermedia including watercolor, gouache, and acrylic.

The American Watercolor Society was founded in 1866 to promote the use of watercolor and watermedia. It holds one of the longest running annual art exhibitions in the United States. Past members include such illustrious artists as Andrew Wyeth, Edward Hopper, Edgar Whitney, and Winslow Homer.

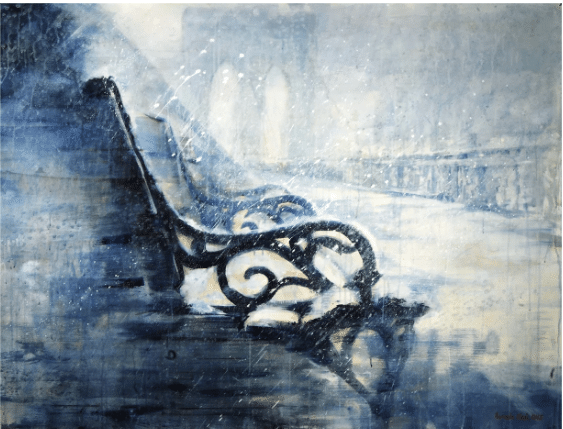

Antonio Masi, First Snow, 42 x 62 in.

As part of the exhibition, AWS President Antonio Masi, will present a talk and demonstration on Apr 25, 2024, 6 PM – 8 PM that will be open to the public. Masi will discuss how his approach to painting delves into evoking emotions and experimenting with mood. Masi will also discuss the process that creates an individual style through the combination of brushwork, the symbiotic relationship with the surface, and the orchestration of colors and composition.

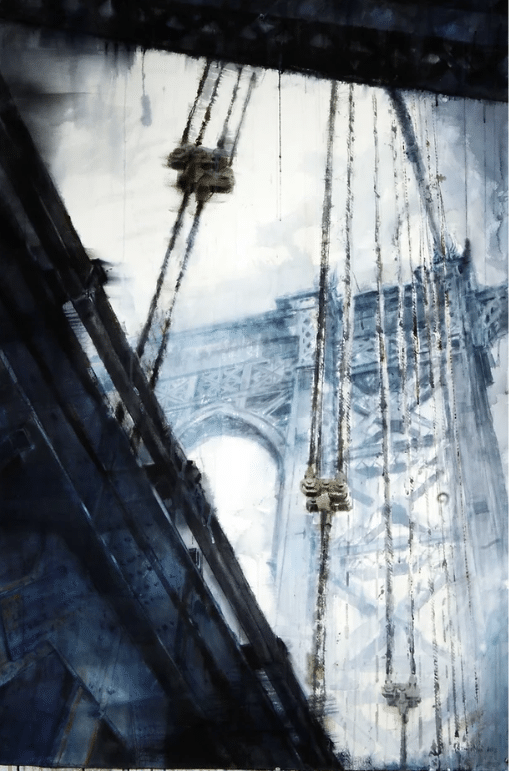

Antonio Masi, Diagonal View, watercolor, 60 x 40 in.

“As one navigates the intricate interplay of elements, one crafts more than just paintings; one creates a dialogue between the artwork and the viewer,” Masi says. “My primary concern, always, is to capture mood and those stirring, overpowering sensations reminiscent of my first glimpse of New York Harbor… In the end, my subjects are secondary to conveying what I feel in the moment.”