The sooner a painting is “good” the better, right? “A painting lives or dies in the first 15 minutes,” an artist I know is fond of saying.

That’s not necessarily how it is for everyone – there are as many ways to paint as there are people moving paint around. Certainly many artists, especially those trying their hand at oil painting, face a common challenge: the dreaded ‘ugly’ stage. (Then again, some artists consciously seek this stage out – watch a video titled “Make a Mess and Fix It!” – the mantra of painter Bridger Barksdale, for example.

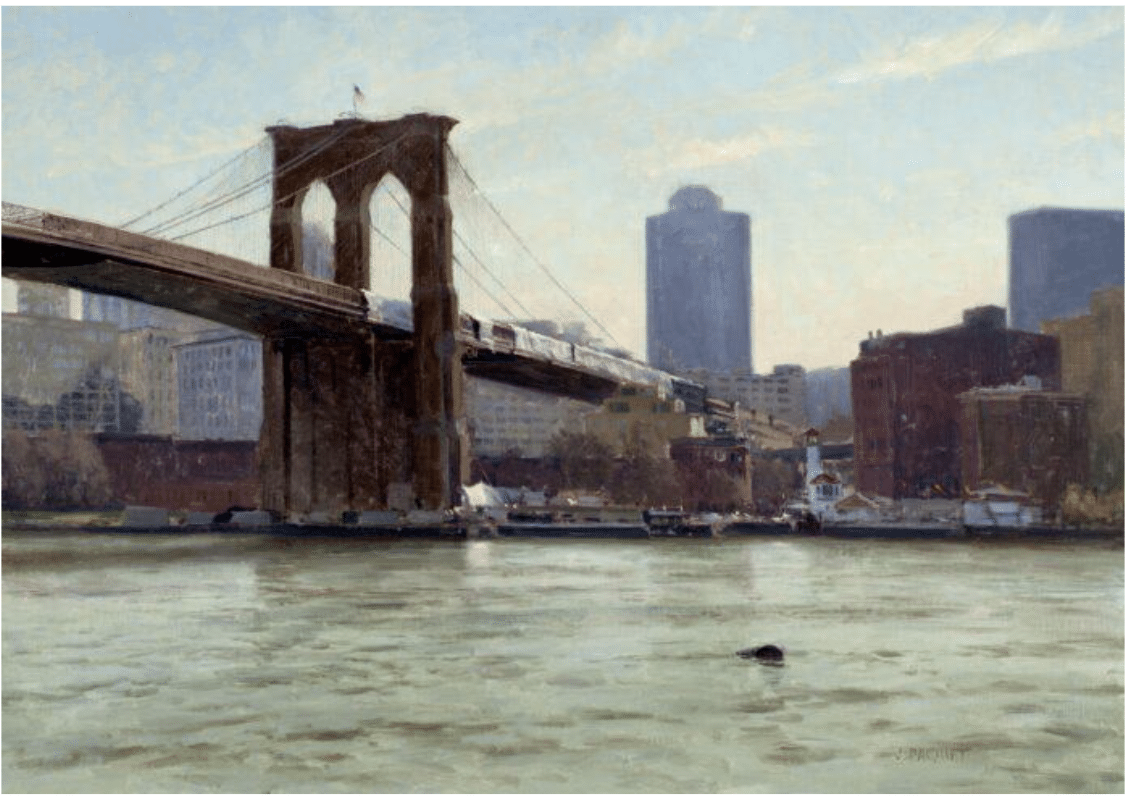

Joe Paquet, “Corner of Kent and Selby,” oil, 24 x 30 in.

But this is different, and it’s a familiar cycle. You work tirelessly on a piece that just doesn’t seem to come together as you had hoped. In frustration, you eventually shelve it. Weeks or even months pass… When you finally get back to it, you’re even less happy with it. Some just trash their work. Others sabotage it out of spite.

Landscape painter Joseph Paquet says there is a better way. “When I was a young student Arthur Maynard (a former student of Frank Vincent DuMond) said to me, ‘The better your start is — the closer it will be to a finish’,” Paquet says. “It was good advice.”

“I don’t buy into the idea that all paintings must go through an ‘ugly’ stage,” he says. “I believe that every stage of a painting can be intentionally and thoughtfully expressed.”

The so-called ‘ugly’ stage can be completely avoided, he says. And you can create a painting that radiates beauty right from the very beginning. The key is keeping mind that at the outset “everything matters,” Paquet tells his students.

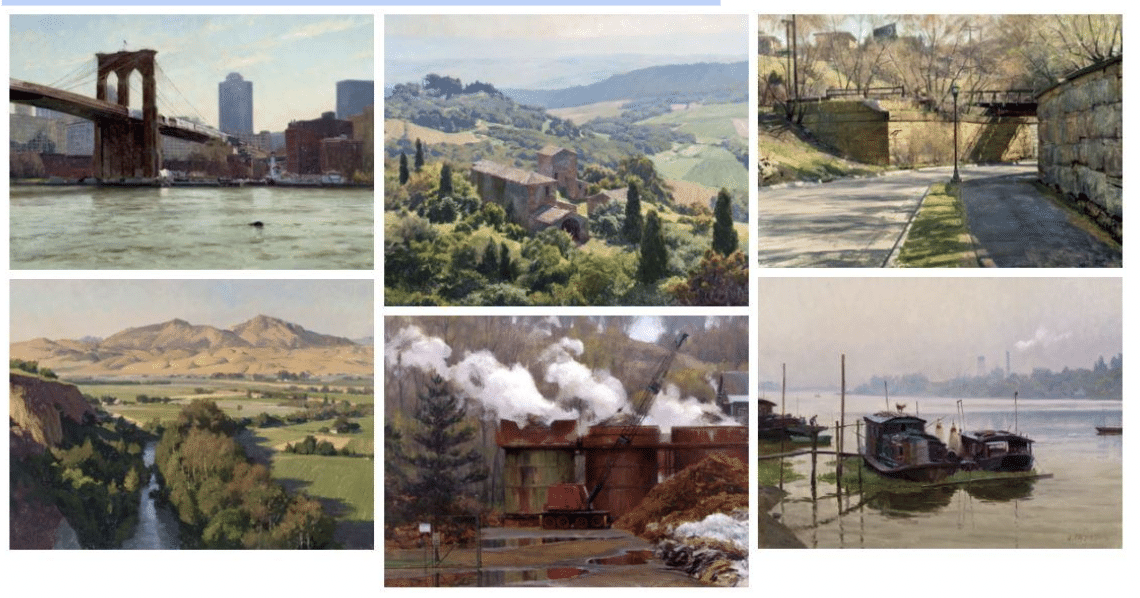

Landscape paintings by Joseph Paquet – seeing them in smaller thumbnails like this emphasizes the structural qualities present at the initial composition and sketching phase that lays the groundwork for a beautifully finished painting.

Paquet points out that there are clear boxes you can check to ensure a strong start that will plant the seeds for a beautiful finish: “The key is to simultaneously bring together both unity and variety, as well as rhythmic connectivity and a clear visual hierarchy.

By traditional definition then:

- Unity is about separate parts working together in a composition. In an artwork, unity creates a sense of harmony and wholeness by using similar elements and placing them in a way that creates a feeling of “oneness.” Variety adds interest by using juxtaposition and contrasting elements within the composition.

- Rhythm refers to the movement within a piece of art that helps the eye travel through the to a point of focus. Like in music, rhythm in art can vary in its speed … some works are more calm and relaxed while others are more energetic and active. Others may even seem a bit off balance if the rhythm is regular.

- In design, hierarchy organizes elements to convey importance through positioning, scale, and color, leading the viewer’s eye through a predetermined path. Emphasis, on the other hand, creates a focal point by accentuating a specific element, drawing immediate attention

Paquet says it comes down to drawing an initial sketch with enough speed and risk to fuel the necessary dynamic balance, rhythm, and hierarchy of forms.

“It is possible to imply extraordinary elegance and refinement at the block-in stage of your painting,” Paquet says. “A beautiful start can make for a more beautiful finish.”

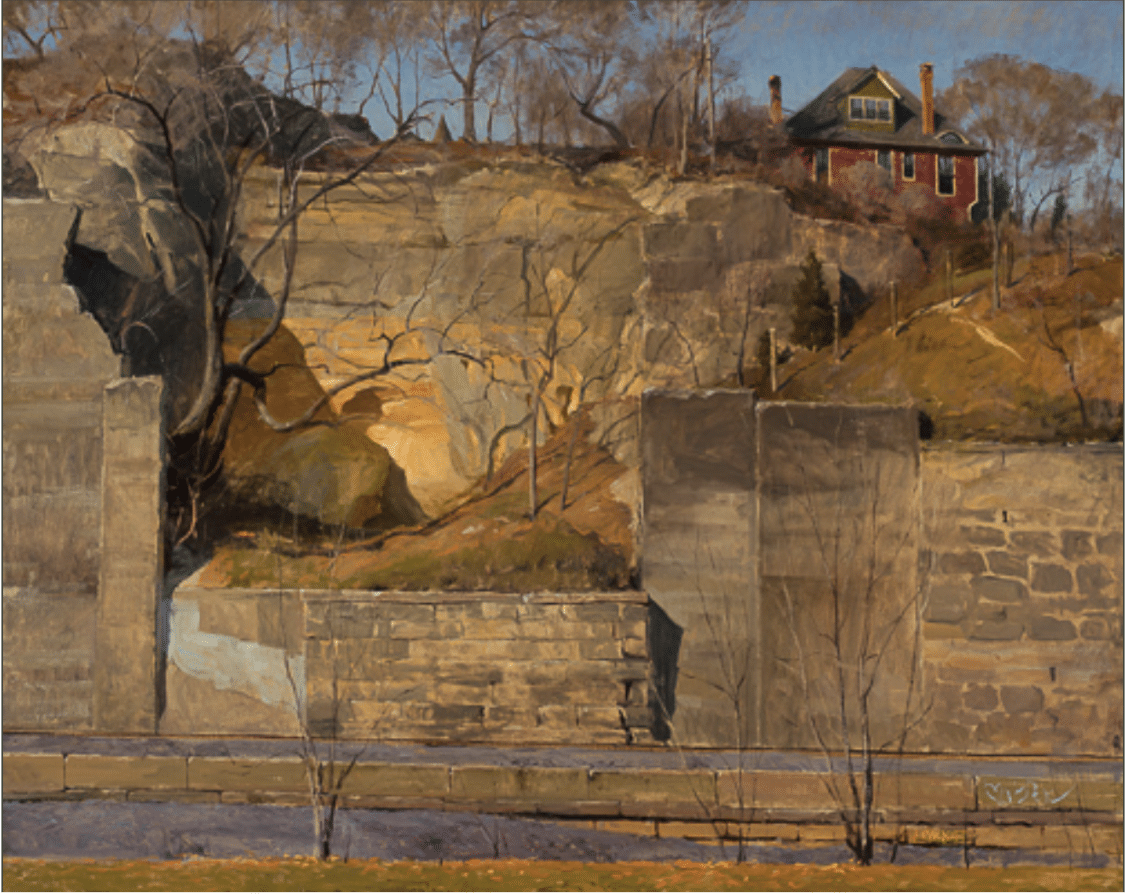

Joseph Paquet, “Cave Shadow,” 40” x 50”

Become a Better Painter at the Plein Air Convention & Expo

Joseph Paquet is going to address this and more in the Pre-Convention Workshop at the 11th Annual Plein Air Convention & Expo, May 2024, in the Great Smoky Mountains. All levels are welcome. Must purchase a ticket to the Plein Air Convention to attend. Limited seats available – register now at PleinAirConvention.com!

Mystery Solved: We Now Know what Wiped Out The Mayan Civilization

Tikal, an ancient Maya city that dates from 800 B.C. to 900 A.D. Laslovarga/Wikimedia Commons

The collapse of the Maya civilization has remained one of the enduring mysteries in the history of global art and culture. For years, evidence trying to prove the various theories had been inconclusive — until now.

The Maya Empire, located in what is now Guatemala, was a cultural epicenter that excelled at agriculture, pottery, writing, and mathematics. They reached the peak of their power in the sixth century C.E., however, by 900 C.E. most of the civilization had vanished completely their great cities were abandoned.

Maya Cave 224 lunette, 6th century CE

The Maya created numerous types of artworks including stone sculptures, murals and paintings, and extraordinary architecture. Much of Maya art was centered around religious themes.

A report in Science has finally given quantifiable evidence confirming the most widely-believed theory to explain how the Maya civilization met its end: drought. The key to unlocking the mystery ended up being located in Lake Chichancanab on the Yucatan Peninsula.

Maya mask. Stucco frieze from Placeres, Campeche. Early Classic period (c. 250 – 600 AD.) National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. Joyce Kelly 2001 An Archaeological Guide to Central and Southern Mexico, p.105 / Wikimedia Commons

For the report, researchers examined oxygen and hydrogen isotopes in sediment from the lake, which was close enough to the heart of Maya civilization to determine the chemical composition and meteorological profile of the regional climate through time.

Previous studies showed that the Maya’s deforestation could have contributed to the dry conditions, decreasing the moisture of the area and destabilizing the soil. It’s not clear how much the Mayans’ agricultural clearcutting and land development was a factor in tipping the climate balance away from their favor. But we do know now what caused their collapse.

Maya ceramics (scan from Miller, Mary Ellen, Maya Art and Architecture. Thames and Hudson, New York, 1999) source: Wikimedia Commons