According to Brueghel

when Icarus fell

it was spring

a farmer was ploughing

his field

the whole pageantry

of the year was

awake tingling

with itself

sweating in the sun

that melted

the wings’ wax

unsignificantly

off the coast

there was

a splash quite unnoticed

this was

Icarus drowning

– William Carlos Williams (Landscape with the Fall of Icarus)

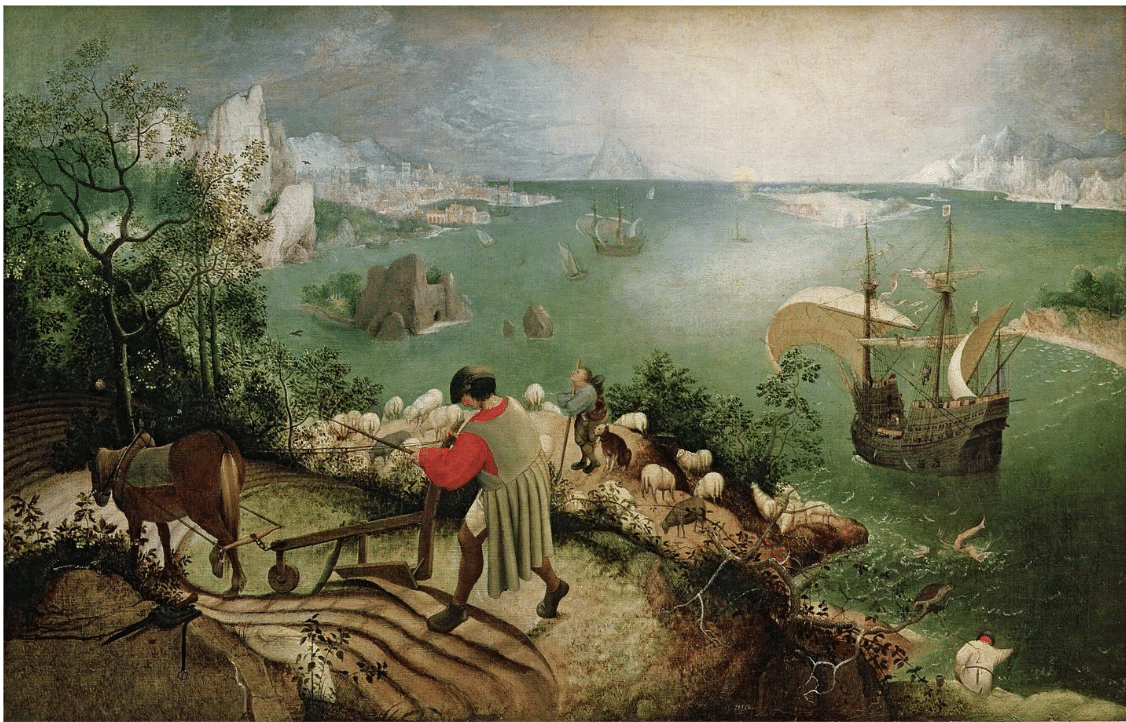

The painting appeared on the market in 1912, unsigned. But its general magnificence, coupled with a multitude of mannerisms peculiar to just one artist in history, left no doubt: it was by the 16th century Dutch master, Peter Brueghel the Elder. However, in the decades since, it’s been proved nearly conclusively that while the image is probably his, Brueghel didn’t paint it, and no one knows who did.

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus is a true masterpiece. The composition is dazzling, and the conceptual idea at its core is so striking and original that numerous curators still identify it as one of the famous Old Master’s finest creations. Many art historians, however, believe it to be a copy, one of several, by an unknown artist of Bruegel’s lost original.

The subject is the mythological hero Icarus, whose genius father (Daedalus) sprang him from an island prison by making him a set of wax wings (and warning him not to fly to close to the sun, which of course the boy did).However, in this painting the “mythical hero” is a minor detail within a wide, modern, unaware world. Despite the mythic timelessness of the moment, the only bit of the entire myth in evidence are Icarus’s legs flailing in the air in the bottom right-hand corner – the kid just dive-bombs backwards beneath the waves unseen, and the rest of the world goes on.

In the painting’s foreground, an industrious ploughman steers his plough with one hand and holds a whip in the other. His face is almost entirely hidden, so it is above all the striking red of his shirt which catches the eye – long before Icarus does.

Art historians see the traditional moral of the Icarus story, warning against excessive ambition, reinforced by the choice to (literally) foreground the humbler figures who appear content to fill useful agricultural roles in life.

The upturned face in the bushes

Surprisingly, a close look finds the pale head of a dead (or dying?) person lying in the undergrowth. Commentators explain this as likely a reference to the proverb “The plough never stops, even for a dying man,” which echoes the painting’s idea of the world moving on from the classical story.

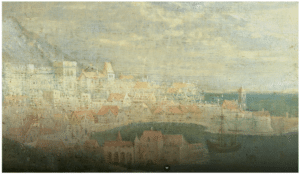

In the background, there’s a beautiful miniature landscape. Painted in a sort of proto-Impressionist style, the artist doesn’t so much depict the architecture as paint the side-lighting of the setting sun off to the right.

The painting with the painting – a dazzling, sun-drenched city harbor.

Just over the ploughman’s shoulder, an odd figure stands center stage in the middle ground, looking up. Some say he’s just daydreaming or meditating – but there’s another painting of the scene, and in this one, it makes a lot more sense.

The appearance on the market of this second version in 1935 only deepened the mystery. This work, in a more modest format, is an oil on wood. It was thought at the time to be an authentic work by Bruegel the Elder and was bought by the collector David Van Buuren in 1951. It is one of the jewels of the Van Buuren Museum collections in Uccle, where it can still be found today.

There are two key elements which differ between these two works:

– in the painting in the Van Buuren Museum (above), we see the presence of Daedalus, Icarus’s better-flying dad, justifying the shepherd gazing towards the sky,

– and, secondly, the sun (which melted Icarus’s wing-wax) is shown not setting but at its height, in better keeping with the mythology.

Dendrochronological analysis (tree-ring dating) on the second version has established that the panel dates from 1577 at the earliest, eight years after Breughel’s death. So that one’s not by Breughel either.

Either way, the paintings preserved in the Van Buuren Museum and the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium are still key works which deserve a place not only on the walls of these two museums, but also in the history of art. All of these issues and debates between specialists are an integral part of this history. It’s a fascinating painting with a heck of a backstory.

Musee des Beaux Arts

- H. Auden

About suffering they were never wrong,

The old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position: how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer’s horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Breughel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

Go and See for Yourself!

Do you love learning about art history? Want to see beloved famous works IN PERSON? Join Fine Art Connoisseur for an exclusive behind the scenes art tour with editor Peter Trippi and publisher Eric Rhoads.

Fine Art Connoisseur Magazine Behind the Scenes art trips are legendary. You’ll see art from a new perspective with excursions to museums, visits with artists, and iconic art experiences which take advantage of our deep contacts in the art world. Guaranteed to create a lifetime memory. We’ve chosen two incredible “art-rich” cities to give you a world class experience.

Hosted by Fine Art Connoisseur Publisher Eric Rhoads and Editor-in-Chief Peter Trippi, this is a continuation of our eleven-year tradition.