The other day, I read something where the author referred to a particular painting’s presence. I don’t think that’s an “official” art term or even something you could attach a single, clear definition to. And yet, I had an instant sense of recognition.

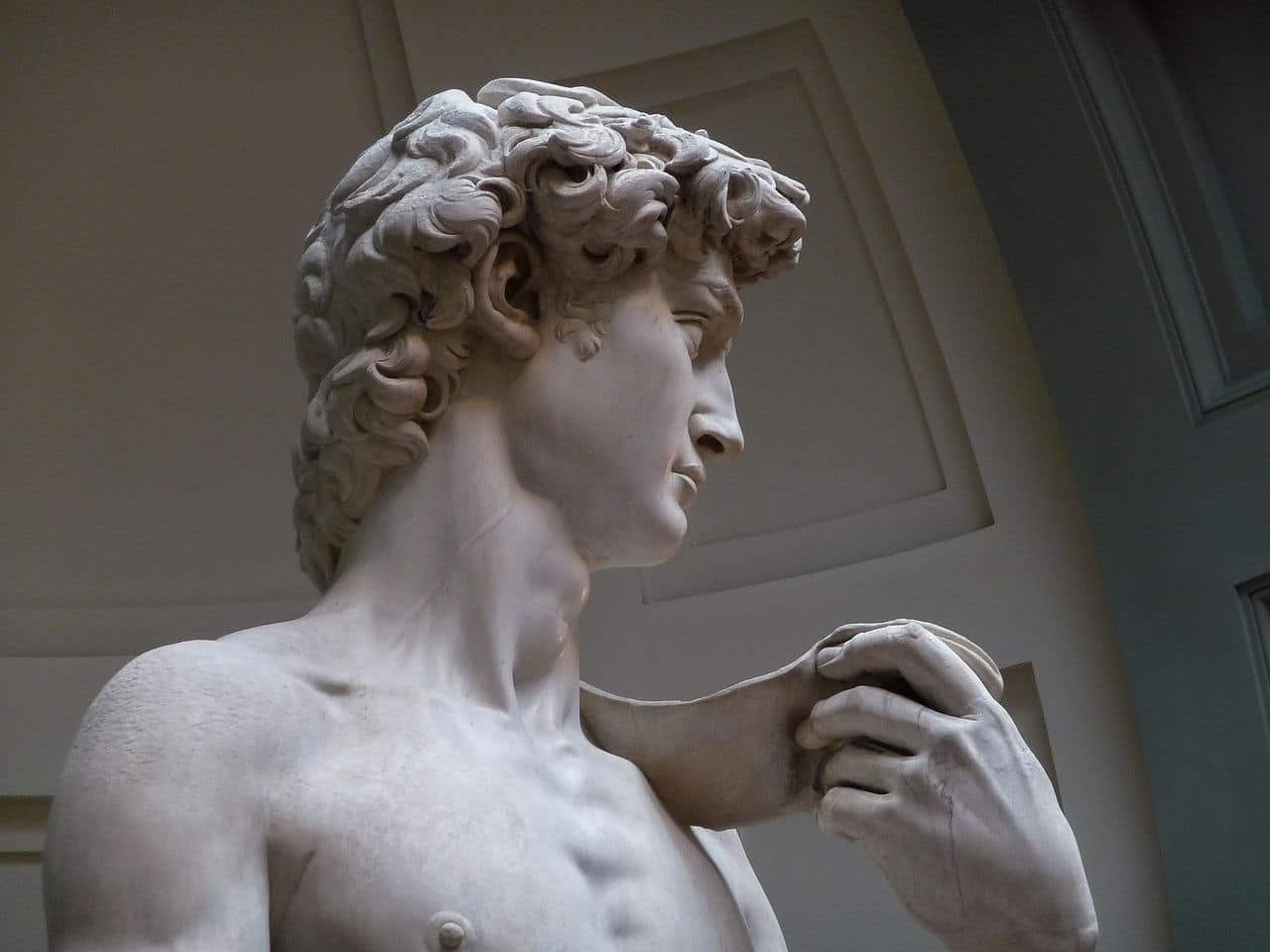

Lascaux cave paintings (photo by Prof saxx)

You sense it from across the room. It only intensifies and becomes more mysterious the closer you get. Some works of art “take up space” more than others. To be sure, your amazing painting might be different from my amazing painting. But what art lover has never felt the palpable energy of a work of art, one that’s not just amazing to look at either, but that comes with a certain gravity or seriousness as well, a work that grabs you by the lapels and won’t let go until the hair on the back of your neck stands up, your breath stops for a second, your eyes dilate like a cartoon character’s, and your slack-jawed open mouth goes wow?

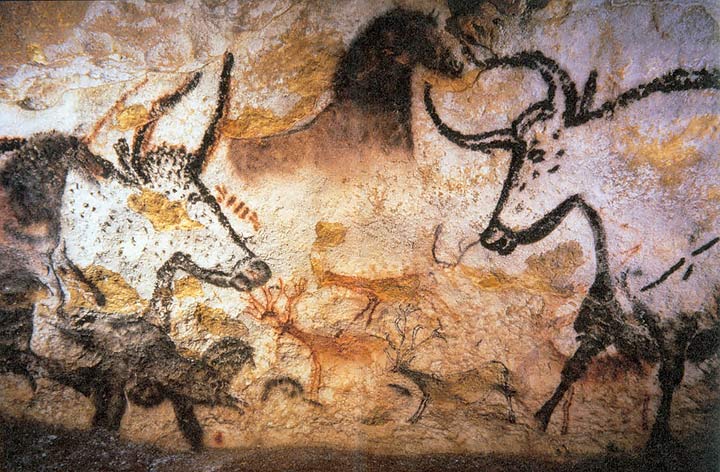

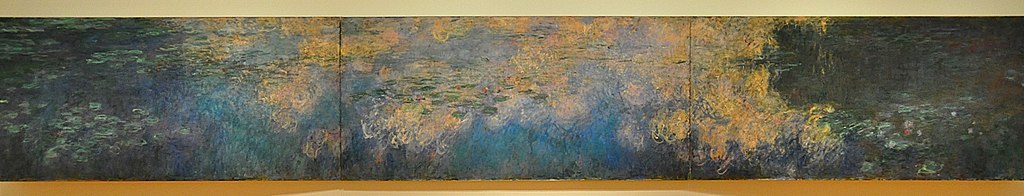

As a yardstick to test any given theory of art, I mentally apply it to a trio of very different greats and see how well it stands up (not just to each individually – it has to apply to all three). I always include the cave paintings of Lascaux, and I often pick Michelangelo’s David, and either Monet’s Water Lilies or one of Jackson Pollock’s powerful abstractions, such as “Autumn Rhythm.” So, do the prehistoric (15,000 year-old) cave paintings of horses and bison have “presence”? I’d have to say, yes, absolutely. The David? Check. Waterlilies? Yep, in spades.

Claude Monet, Waterlilies, (Uploaded from the Wikipedia Loves Art photo pool on Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/groups/wikipedia_loves_art/pool/ {{PD-US}} )

But where does this presence come from? What is it and of what does it consist? It’s not just technique, the three disparate examples prove that, and it’s not all about content either (no one knows what the content of the cave paintings was, if any, nor that of the other two either for that matter). It’s probably some kind of intertwining of form and content. Or not.

Personally, I’d call this kind of art meaningful though, even if I couldn’t (and wouldn’t want to) reduce any of it to a single “statement” about what it means.

Many artists detest the notion that art should “make a statement” at all, and I think this is precisely because of an artistic devotion to, and love of, the visual qualities of the medium and the world seen through the painterly lens. They instinctively know that art comes from a wordless, mysterious place that has little enough to do with “statements” about anything. They get that the strongest art should not, indeed cannot, be reduced to a single “message” without risking the loss of its power – without, that is, compromising its presence.

So, for what it’s worth, I wish your art lots of presence. Whatever that means.

Miro Weighs In

“My favorite schools of painting are as far back as possible: the cave painters – the primitives. To me the Renaissance does not have the same interest. But I have a great respect for the Renaissance. In the work of Leonardo da Vinci I think of the “esprit” of painting. And in the work of Paolo Uvello, it is the plasticity and structure which interest me. This, I think, happens often in painting. Some painters are better for the spirit and the force they represent. And other painters one likes because they are better as painters. With me, I find that I like Odilon Redon, Paul Klee, and Kandinsky for the “esprit.” As pure painting – from the point of view of plasticity – I like Picasso or Matisse. But both points of view are important.”

– Joan Miro, from an interview, 1947