Though at a glance this painting may look like “just” another Barbizon-inspired landscape, The Mill-Pond by nineteenth-century American painter George Inness holds clues for contemporary painters looking to liven up their landscapes with movement and color and suggestion.

This is a painting of “ordinary” American scenery (little is overtly “majestic,” sublime or Romantic about its subject). And yet, it works a kind of magic. Inness was a spiritual painter, and here he invites us to experience the visible world as a portal into the invisible.

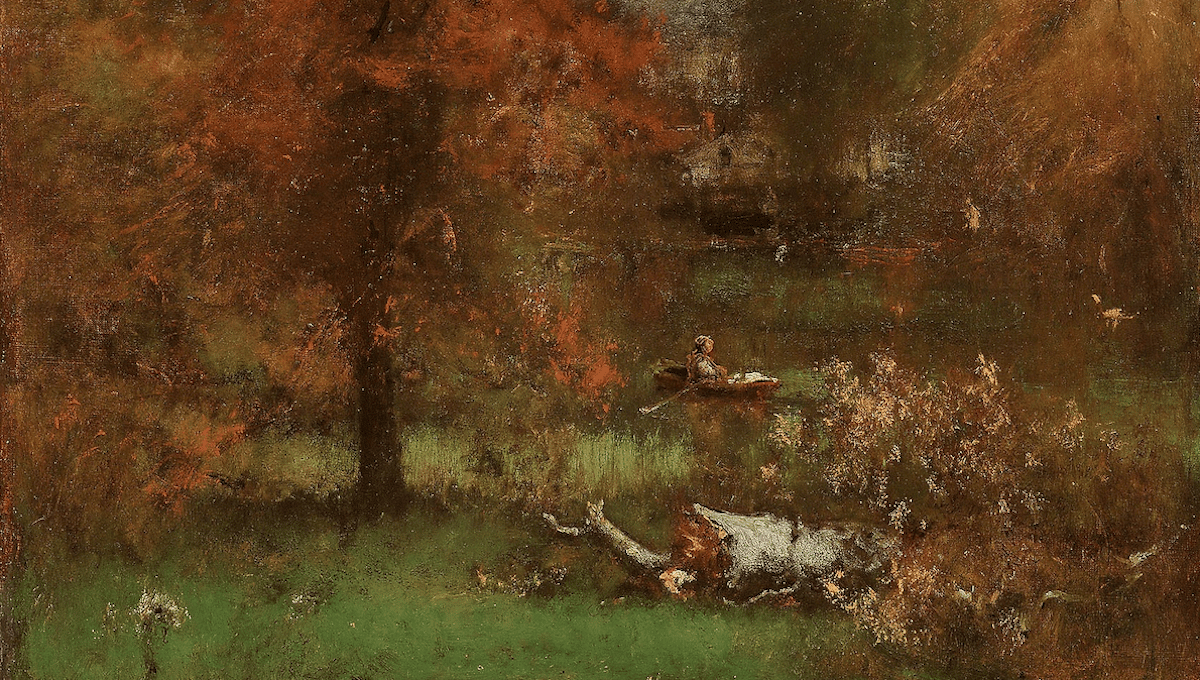

Right off the bat, this painting captivates the viewer through harmonious, saturated tones, a composition designed to instill a sense of life and movement, strong primary (and secondary) “points of interest,” and, most important of all, a kind of unifying vagueness or fluidity of line that comes from brushwork that’s loose, yet graceful, and disciplined.

In such mid-career and later works, Inness backs away from meticulous detail to plant suggestions of his subject, and throughout this work, he rather magnificently suggests rather than tells.

In such mid-career and later works, Inness backs away from meticulous detail to plant suggestions of his subject, and throughout this work, he rather magnificently suggests rather than tells.

Inness doesn’t copy nature; he opens it up for us to re-imagine. Lured in by the lack of precise detail, we become intuitively involved in completing his subjects out of the flickering stuff of memory and desire.

The composition is stacked in thirds. Our eyes see the big tree against the sky first. If they wander off into the sky, it is only to be guided back to the middle ground, the main site of the action, by the linear edge of a hidden oval. Coming back down, we’re conducted to the bottom of the picture.

There we encounter the fallen log and are pointed back to ascend for another lush visitation through the passage of that tree.

Following the cloud shapes again, we return down through the tree once more and back to the log, but this time perhaps we also see the figure in the rowboat parallel to it, and after that the suggestion of the mill dam on the opposite bank.

Closeup: the figure in the rowboat, and after that the suggestion of the mill dam on the opposite bank.

Should we be tempted to savor for too long the deft suggestions of mill structure or the wildflowers and shadows in the foreground, our eyes will inevitably be led back by the log’s projecting limb to the mass of tree that first caught our attention. And from there, we can repeat the same visual circuit we have just enjoyed. This constant roaming of our eyes helps Inness convey the sense of animation that he perceived in nature and wished to express in paint.

The artist’s son, George Inness, Jr., described this painting in his biography of his father, Life, Art, and Letters of George Inness:

“The Mill-Pond” is an upright, and depicts a tall, red oak, which fills most of the picture, and by the very redness catches the eye. It is necessary to sit before this canvas a while trying to grasp its full meaning.

“At first you are impressed only with this great mass of reddish gold, standing out in intense relief against a patch of blue sky. A pond fills the middle distance, across which are trees so indistinct and so clothed in mystery that at first glance you wonder what they are. They are painted in so broad and indefinite a way that they seem to lose all sense of individual forms, and in contrast to the “Catskill Mountains” become a mass of green, partly enveloped in the sky.

“But as you look more carefully you begin to make out certain undefinable forms, and little lights and shades that take on all sorts of shapes that you were not aware of at first. And now straight across the pond your eye catches the dam as it leads the water to the mill. The mill is not visible to the human eye, but your fancy tells you it is hidden snugly behind the trees.

“The charm of this picture is its color and mystery, and but for a boy and boat upon the lake it might seem monotonous; but this gives a spot of light and lends human interest to the scene.

“In a brilliant green foreground a gnarled and rotting stump, with whitened bark, stands out vividly, bringing to completion a beautiful composition.” (George Inness, Jr., Life, Art, and Letters of George Inness, pp. 256-259)

The curators of the Chicago museum that owns the painting have this to say:

“A distinctive landscape painter of the 19th century, George Inness excelled at capturing the poetics and mood of his environs, finding spiritual resonances in nature, from its grand vistas to its quiet nooks. The Mill Pond depicts a sylvan setting, in which a small figure rows a boat in the pond at middle distance. Brilliant pigments of orange, green, and blue electrify an otherwise tranquil scene. Through color and atmosphere rather than line or detail, Inness communicated an intensity of vision, fueled by an individual encounter with nature.”